Designing with Water Plants

I feel like I’m working backward: First, I told you about a gargantuan water lily and its very specific requirements, then I offered a more general look at water lilies that will thrive in almost any pond. Now I’m going to give you some ideas and tips for designing with all types of water plants.

It might have been more logical to approach things the other way around, but the important thing is that we’re ready to complete the package and talk about ways of incorporating lilies and water plants of other sorts into beautiful, overall planting designs.

As always, I will avoid getting too specific with recommendations. Instead, I’ll stick to basic design principles you can apply using your own tastes, local plant options and familiarity with your clients’ desires. (I also want to hear from you: If you have a different perspective or simply disagree with one or all of the design elements I isolate here, please let me know!)

GETTING STARTED

Let’s start with a given: Unless you’re working with a very contemporary or highly structured formal design, water plants will always be at home in your ponds. (This is no slap at contemporary or formal designs. The simple fact is that many of these watershapes are meant to be plantless.)

Another given is that the main difference between planting in soil and planting in water is the grade. With a watershape – and even with watershapes featuring more than one pond or level – you’re always placing plants on a horizontal plane. You don’t want to end up with a “flat” look, so bringing dimension and depth to your design with the plants themselves is very important.

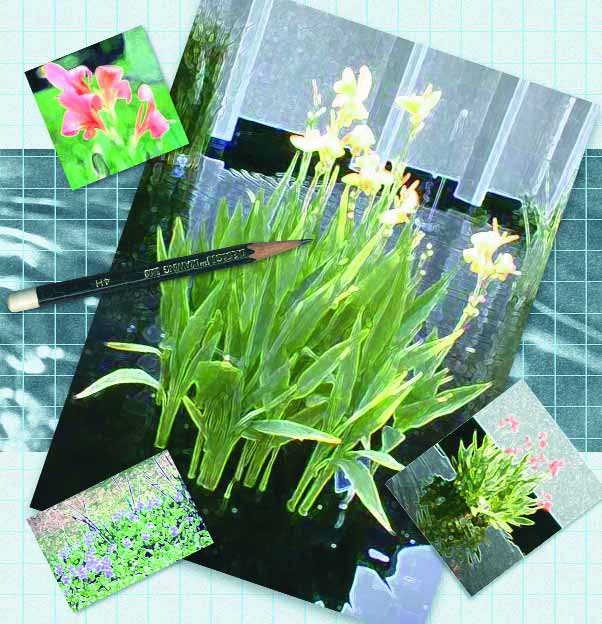

For that reason, I’ll be illustrating this discussion with water lilies, water cannas, and water hyacinths: Each has a different height, color (primarily in their flowers), texture, and shape.

The differences in these characteristics are important. Even if you and/or your clients loves water lilies above all other flora, a pond planted exclusively with water lilies, no matter how many different varieties or colors you assemble, will all lay at about the same height relative to the water’s surface. Even their flowers typically will bloom at about the same level. Unless you’re looking for a flat, even design, you will probably want to mix in plants of other species to give your design more depth and dimension.

You could, for instance, add water cannas, which are tall, thin plants with strappy leaves and vibrant flowers. You might also want to mix in some water hyacinths to add some plants at a lower height. And of course, in designs where variety is the goal, you have many more choices available to you than lilies, cannas and hyacinths. As always, I recommend that you check with your local suppliers to find good choices for your area.

The idea is that you want to create a cohesive and interesting design by varying heights, colors, textures and shapes within the specific context of the size, shape, location and exposure of your pond.

[ ] Height. As I’ve already mentioned, using plants of all the same type can give you a flat look, no matter whether you’re using water lilies or tall grasses. If you vary the height of the plants, you will create more interest in your design.

It’s important to start by determining which plant (or plants) will serve as the cornerstone of your design. If you decide to use water lilies as the focus, for example, you should probably think about adding in tall grasses or another vertical element that proportionally fits the pond.

That proportionality is important. If you have a 5-by-5-foot pond, you might want to think twice before inserting a plant that grows up to 10 feet high. It will simply be too big for a pond of that size. A better thought would be to put in some smaller plants with graduated sizes to fill in the gap between the grasses and the water lilies.

When determining how many plants to use and what their sizes should be, you also need to consider the surrounding landscape. Remember: The pond doesn’t exist in a vacuum (even though evaporation might lead you to believe it does)! In fact, trees and shrubs just outside the pond might lend the height or depth you need to complete your design. Also, the margins (or borders or edges) of your pond might contain plants that look as though they blend with the pond – or may actually dip into the pond and blur the edges.

[ ] Color. I’m not just talking about flowers when I refer to color. You don’t need to look very closely to perceive that there are more shades of green in plants than you can count.

Although you do want to select flowers with colors your client likes, you can add lots of variety to your color palette by choosing plants of varying shades of green. There are also many water plants that come in shades of burgundy and black.

|

The Toxicity Issue It seems that I’m always reminding people of one key point as they set up planting programs for their watershapes: Be careful of what you put into your pond! Many items you might choose to use as elevators or shelves, for example, can contain toxins that could harm plants or fish. That in mind, it’s always good to run your ideas by your local nursery or pond-care professional to determine what is safe to use in these situations. You wouldn’t want to poison your investment! — S.R. |

Watch the surroundings as well: If you pick up color elements that already exist in the area beyond the pond or that are planned for future construction, you’ll have gone a long way toward tying the whole backyard environment together when the project is complete.

[ ] Texture. Plants generally fall into one of three texture categories: fine (those with a feathery appearance that tend to have small or thin leaves), coarse (which have a more dominant appearance and tend to have large leaves) and medium (plants that make up the huge category between fine and coarse).

Your design will look flat if you choose all of your plants from just one of these categories, just as would be the case if you used plants that were all the same height. Variety will keep things interesting and make your pond more visually attractive.

[ ] Shape. I’m beginning to sound a bit like a broken record here, but one last time: Vary the shapes (or forms) of the plants you use to keep things interesting. Water lilies have a flat shape, while water cannas have a tall, narrow shape and water hyacinths have a low, rounded shape.

Used as a mass, any single plant type will look flat, and variety is once again the key. By varying the shape of your plants, you lend interest not only to the plants in your pond, but to the pond itself, the surrounding garden and even the spaces beyond.

[ ] Placement. There are two issues involved in placing plants in a pond: where you place the plants relative to each other and the main viewpoint for the pond; and how you manipulate the size of containers and heights of a plant to get more (or less) from those plants.

First, let’s address the view of the pond. As with other elements of a landscape design, you need first to determine the direction from which people will be viewing the pond as well as how much of the pond you want them to see from that vantage point. This generally will lead you to place lower plants in front, with larger ones in back to draw the observer’s eye across the pond and up, most likely leading to other plantings or architectural features behind the pond.

The other important feature of water-plant design involves playing with the flat surface you’ve been given by placing plants at different levels inside the pond. When most people look at a pond with water plants in it, they see only what is above the surface. Use that to your advantage and play visual tricks that hide your secrets.

Below the waterline, you can use bricks, concrete block, upside-down pots and a variety of other “elevators” to place plants at different heights. You might even want to design shelves into your pond to accommodate plants at different locations throughout the pond; this, of course, requires careful planning to make sure you put your shelves in places you want plants. Or you can set up the pond with sharply vertical sides, which allows you to place plants right at the margins – something you can’t easily do with gently sloping sides.

***

My fear in offering this quick review of principles for water-plant design is that it’s too much information for easy absorption at one time – and that it is simultaneously too little information to offer a truly practical guide. That in mind, please use this as a point of departure that leads you to the right questions as you think about plants and your own ponds.

There’s also much more to be shared on this topic – on water treatment, on the potting of water plants, on using different plants to balance a pond’s ecosystem and much more. I’ll get to some of these key topics in future columns; in the meantime, if you have specific questions on how to design with water plants or want to share your own design ideas, please enlighten me: I love learning new things!

Stephanie Rose wrote her Natural Companions column for WaterShapes for eight years and also served as editor of LandShapes magazine. She may be reached at [email protected].