On the Road

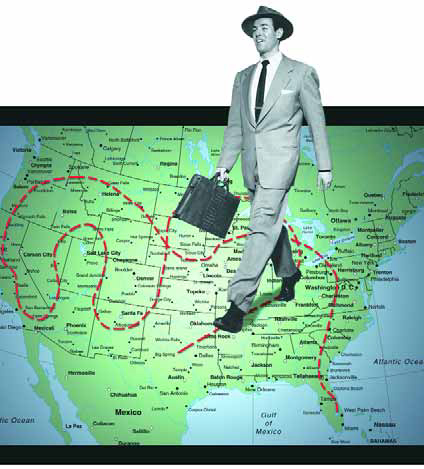

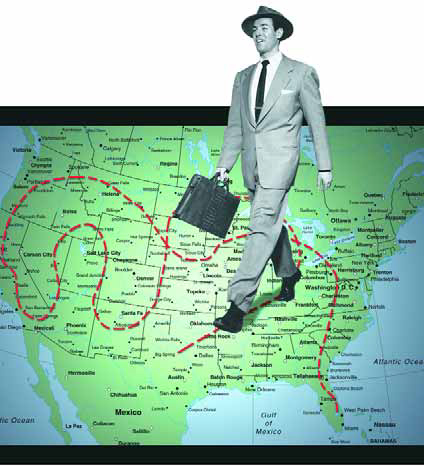

Working outside your home region is exciting stuff. It opens you to a broader and often more dynamic arena for doing business and lets you work with new sets of clients and their architects, landscape architects and designers. The projects are typically interesting and often unusual, and you can make a good dollar while reaping the personal benefits that come with travel to faraway places.

On the one hand, being in demand for long-distance projects represents a measure of success in your business and shows the high degree of confidence others are willing to place in your skills. The simple fact that clients are willing to pay you to fly to their hometowns so you can participate in their projects speaks volumes about you as a professional. On the other, however, playing the game at this level also comes with elevated expectations for your performance and a certain level of risk on your part that says you must be fully prepared to meet the challenge.

In other words, no matter whether we’re talking about day trips by car or by plane, overnight forays to other parts of the country or even extended trips abroad, working “out of town” spells opportunity – but only if you’re prepared to deliver the goods once you arrive.

TRAVEL BY DESIGN

Although the majority of my watershaping jobs are still within about a hundred miles of my Miami home, the work I’m doing beyond local bounds is becoming a larger and larger part of my business each year. At first, these projects were few and far between, but as time has passed and I’ve grown as a watershaper, I’ve begun experiencing a sort of snowball effect where one new long-distance job leads to another.

Almost all of these opportunities have come by way of some sort of referral. In fact, to this day my primary means of “promotion” has mostly to do with kind words from satisfied customers along with my involvement in Genesis 3 and a certain level of interest generated by my web site. I’ve never considered deliberately promoting services outside my area; instead, these projects have come as a natural outgrowth of things I’ve been doing to support my industry overall and my own work in the South Florida area.

Another fact of the matter is that this work is mostly about design. People ask me to travel not because they want me to drive a backhoe or shoot gunite; rather, they’ve seen my work or heard about it from friends and they want me to apply what I know in their backyards on a conceptual basis.

I take this increase in jobs in far-flung places as a sign that watershape design is becoming more important to greater numbers of architects and their clients. In that light, people who start out their careers with an emphasis on design – architects, landscape architects and landscape designers – are more likely to find this out-of-town work than are those who’ve come at watershaping from the contracting side of the business.

This all makes sense, because information technology is making the world shrink for designers. The work can be done anywhere there are phones and faxes and modems, and it’s not terribly expensive or impractical to bring in a designer from a distant location to work on a given project. Just the same, when clients or architects are willing to absorb that expense, it invariably means they’re serious about achieving something special.

The tough thing for the watershaper is that this sort of work is unpredictable. These projects emerge on their own schedules, and there’s really nothing you can do to force the action beyond doing well when you’re called into service. It’s like anything else: The more you work on this level, the more likely it is that you will continue to do so. The community of architects and high-end clients is relatively small, and you can rest assured that the word about capable watershapers travels, fast or slow.

In my own experience, for example, one thing has certainly led to another. I’m now working on my third project on the island of Bermuda, and two more are in the offing. For my current project, I was contacted by an architect in Bermuda who had received my name from a stateside architect. For the two prospective jobs, I was contacted by a subcontractor who was working for a client building expensive homes on spec, complete with elaborate swimming pools.

PREPARED TO RESPOND

Even a few years ago, I would never have imagined setting up a niche on that beautiful Atlantic island – but as opportunities have come my way, I’ve been ready to make the most of them. In each case, the contacts grew from the client’s desire for quality watershape design – and that’s almost invariably the case when I’ve been called on to take my show on the road.

But there’s more to succeeding in faraway places than being a good designer. You need to be ready to do what comes and react quickly to opportunities as they arise.

I attribute my own growth in this arena in part to my dogged policy of returning all phone calls as soon as possible. And when I do speak with someone directly, I always approach the situation with an open mind and open ears, because I never know where these contacts will lead.

Sometimes, the projects are straightforward; other times, they’re unusual or elaborate. Either way, what I’ve run into over and over with these projects is a client looking for something truly beautiful and exciting. My current project on Bermuda, for example, will be the island’s first perimeter-overflow pool.

I’m also preparing to work on a project in Chicago that calls for an unusual indoor/outdoor pool. What we’re envisioning in this decidedly non-tropical climate is a single vessel divided into indoor and outdoor portions by a retractable acrylic panel that can be raised out of sight, lowered to water level in summertime to keep bugs outside and lowered all the way to the floor in winter so the exterior portion can be winterized while the indoor portion stays in use. There are lots of details to be worked out with this one, but I’m confident that the engineering and materials can be worked out to everyone’s satisfaction.

Roadwork can also mean participating in large-scale jobs in which other architects and designers are already involved. As I’ve discussed before in this column, this requires a high level of confidence in your own abilities as well as flexibility and basic people skills.

I’ve been in situations where I’ve been asked to correct problems with existing designs, for example, and I’ve felt a certain level of resentment of my role on the part of other members of the “design team.” These situations can be intimidating and require a great deal of self-confidence and presence of mind to achieve positive outcomes.

When you get right down to it, participating in projects that take you out of your usual environment means you need to have a lot on the ball in terms of your own know-how and your ability to communicate. And one more thing: Once you do become involved in an out-of-town project, you need to set up a fee structure and contractual relationship that makes sense for both you and your client.

DOTTED LINES

You can approach fee structures in any number of ways. For most jobs, I quote a per diem fee for a site visit, plus all expenses. With others, I propose a fee for doing all the work without ever going to the site. (Either way, my design fee is separated from incidental expenses I incur, including travel, the cost of long-distance calls and overnight shipping, among other things.)

In the (rare) no-visit scenario, the contract is very similar to the one I use for jobs close to home, with the exception that I define what I need up front with respect to site plans, soils reports, architectural drawings and other information I’ll use in developing a design.

To be sure, projects of this sort are much less common than those that involve a site visit, but they do rise up from time to time. For example, I once designed a project in Bolivia without actually traveling there. It was a complicated job with a multilevel swimming pool and a complex set of associated waterfeatures, and a whole lot of what I did was structurally associated with the house itself. The existence of detailed architectural drawings made this project possible, sight unseen.

In most cases, however, the clients and I will opt for at least one site visit – and I much prefer working this way. There’s really no other way to get a feel for the client, the setting and surrounding environment unless you go there in person.

When these trips arise, it’s necessary to be ready with a site-visit fee that will make the trip worth your while. After all, time spent traveling to projects is time away from home and family – and away from the office where you could be working for other clients.

I separate this basic fee from any travel and accommodation expenses that might be incurred because what it costs to fly to a particular location can vary quite a bit depending on the time of year and how far ahead you make your arrangements. If the client wants a flat rate for my visit that includes everything, I’ll set an advanced-purchase constraint so I know I won’t be losing money as a consequence of having to book a flight or a hotel at the last minute.

In any case, my quotes include a clear description of what my services will and will not include. I start with a “file origination” fee as well as a fee to cover meeting time with the client – to review concepts, select materials and polish the design – and something to cover the time involved in creating plans and drawings. In situations in which I’m not sure how long things will take, I’ll offer quotes for return visits and/or an hourly rate for work I do at home that goes beyond the scope of the initial site visit and design preparation.

In some cases, clients or their architects will want me to generate a quote for staying involved in the project after the design is complete, whether it’s performing site inspections at key points along the way or helping to hire contractors (if any are to be found locally; if they’re not, I’ve set up fees for those rare occasions when I’ve had to bring in my own subcontractors to perform certain tasks).

PRE-FLIGHT CHECK

Any way you slice it, to be successful in working away from home, you need to make sure that you’re paid for your time – which usually means pulling what you do apart in more ways than you’d ever have to do in thinking about a cross-town job.

When you work outside of the United States, for example, there are lots of basic issues to consider: Is your passport in order? Are their restrictions on the work of non-resident foreign nationals? Are there local customs that should be considered in client and contractor relations? Are there features of local business or social protocol you need to know about? Will you need an interpreter? Do you need inoculations against various exotic diseases?

For all that, the biggest issues you need to settle before you travel to faraway places (even within the United States) are more of the internal/personal variety. Specifically, you need to be sure you’re not getting in over your head. Not everyone has the skills required to operate at this level, and if you don’t have supreme confidence in your design and practical skills, you probably should think twice about going on the road because some lofty expectations will be coming along for the ride.

You can’t just wake up one morning and decide that you’re going to start designing jobs at geographic remove from your usual space. It takes patience and the careful building of a portfolio and reputation. It also takes an awareness that you never really know where these projects come from, so you need to pay attention to every client you serve because he or she may lead you to someplace entirely unexpected.

You also need to know the ins and outs of collaboration, because these contacts often introduce you to projects that are already in progress with entrenched design teams. In these cases, you’re usually being brought in to solve problems, which means that you have to be resourceful and know where to go to get product, material or engineering issues resolved.

And when you do land a job that’s beyond a comfortable day’s trip from home, you’re almost sure to find yourself in situations that will be challenging, exciting and (we all hope) professionally satisfying. If you’ve spent your career developing your knowledge, skills and confidence, such trips will certainly become part of your ongoing watershaping adventure.

In my experience, I’ve found the road to be a wonderful place to ply the watershaping trade, but it’s one that requires the very best I have to offer. In that respect, working far away from home isn’t much different from designing watershapes for your neighbors down the street.

Brian Van Bower runs Aquatic Consultants, a design firm based in Miami, Fla., and is a co-founder of the Genesis 3 Design Group; dedicated to top-of-the-line performance in aquatic design and construction, this organization conducts schools for like-minded pool designers and builders. He can be reached at bvanbower@aol.com.