Bridging the Design Gap

As a contractor, do you ever wish that you could avoid fussing with clients about design and could instead just get down to the business of building watershapes and getting all the details right? Do you ever think you’re wasting the time you spend on design, because you know your prospects might go with another contractor despite the time you’ve spent drawing pretty pictures?

Not every watershape contractor will answer “yes” to the first question, but I’m sure most of you have at least thought “yes” about the second one. That’s because most contractors I know don’t charge for design, at least not directly. As necessary, you’ll hire graphic artists to produce drawings for presentations, but in a competitive world in which other contractors usually don’t charge for design, you have a hard time charging for this service for fear of losing potential clients.

More clients these days are insisting on good design work, however, which pains contractors who’ve been asked to perform for free – especially if it starts taking up too much time. In this anti-creative environment, “design” becomes little more than a sales tool – some pretty sketches not to be examined too closely, drawings that are “representations” rather than actual plans.

So what’s the solution to the design dilemma? My recommendation is to find a good landscape architect or designer and pay him or her on a per-project basis. Here’s why, along with information that’ll be helpful in setting up a strong relationship with the designer of your choice.

THE BIG PICTURE

Truth is, no one is really good at everything, especially not all at the same time. If you’re selling, marketing, designing, supervising job sites and running a business, something’s probably getting shorted to make room for the rest – with design often suffering the most.

Most contractors recognize their limitations on the job site and hire excavators, plumbers and electricians to perform key tasks. So why not hire design experts in the same way?

For starters, landscape architects and designers are trained to deal with the whole picture. In fact, most of us would rather design the entire site than just one part of it, so there’s a good chance that we’ll be able to address all of the client’s needs, including the watershape. To us as designers, the waterfeature is just that – a feature, not the entire show.

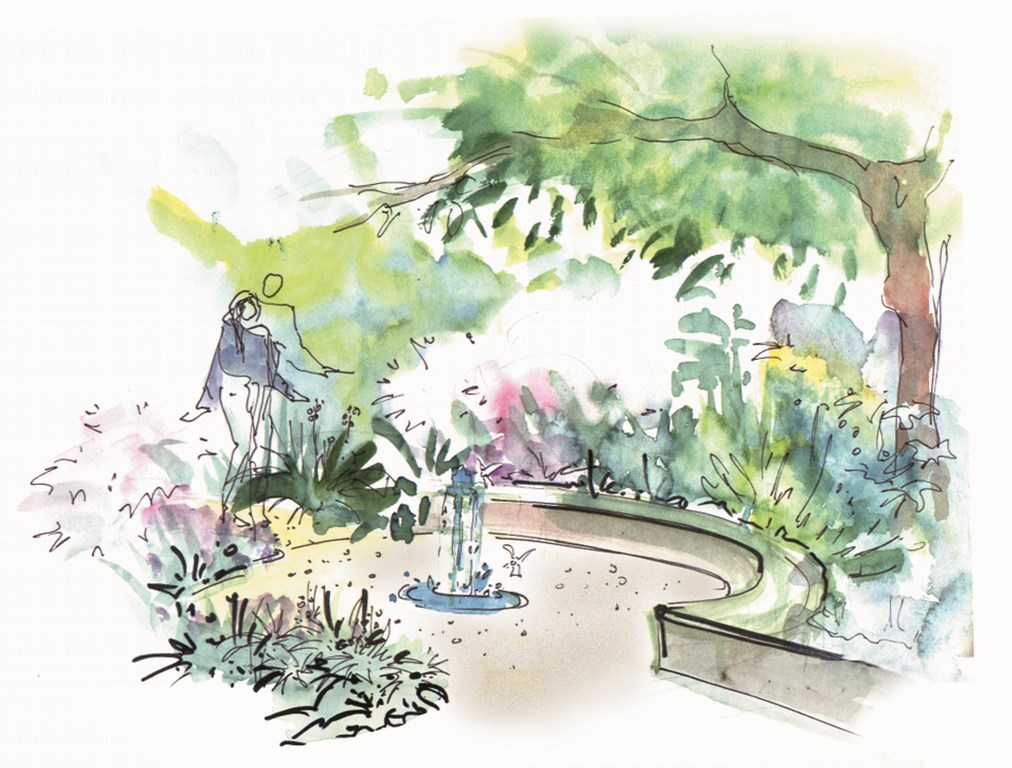

| A designer’s capacity to look at the big picture and integrate a watershape with the entirety of its surroundings is an asset to any project. It’s not just about the vessel: It’s about trees, plants, shade structures and the way they all work together to create an environment clients will live with for a very long time. |

This whole-picture approach has real value these days, because prospects are more sophisticated when it comes to design integration and are much quicker to dismiss designs that don’t consider the every aspect of the setting.

They’re also quicker to act when they aren’t satisfied: We’ve had a number of clients call us after a pool has been installed, asking us to link it back to the house and to the remainder of the landscape. In other words, these are clients who are so unhappy with a pool “design” that they’re willing to pay a landscape architect and another contractor to re-work the site. Wouldn’t it be better to take care of these issues up front with an integrated design?

Beyond integrated approaches, another thing landscape architects bring to the table is time spent in studying, applying, reviewing and (one hopes) perfecting a wide range of styles. Many of us have studied art and know about proportion and color theory, for example, and we’re familiar with drawing, sculpture, art history and the work of other designers from around the world. This gives us a strong background to draw from, and because most landscape architects like to produce original work, we very often strive to create custom styles based on individual client needs.

As a contractor, you can take advantage of this by letting a designer meet the client with you to suggest approaches to the project. No designer can guarantee that a client will choose you over a competitor, but the mere fact that you have a trained landscape architect working with you gives your presentation more clout and often makes for a better fit with the client’s overall wishes.

Professionals designers tend to push the envelope a bit, too, so the projects often end up being interesting to build.

INSIDE TRACKS

Let me emphasize a key point: This process of integrating a watershape into an overall design increases the watershape’s value because the watershape “agrees” with the design; moreover, it positions the contractor to install additional hardscape structures that might not have been included in the project had the water alone been the focus.

| Good designers don’t need huge spaces to get the job done. In this case, a very small yard downslope from a golf course created a need for privacy that was met by setting up a retaining wall inset with a raised bond beam that creates a planter. It’s an elegant look that maximizes use of a tight setting. |

In other words, working with fully integrated designs enables you to profit from whole projects, not just their watershapes.

One of our recent jobs, for example, involved a client who wanted to create a contemporary, Provence-style garden on a small sloping site – vegetable garden, deck, spa, two patios, pool, waterfall, flower gardens, decorative rockwork and a pad for an RV and boat trailer – all on about an eighth of an acre.

|

Welcome to the 21st Century Most landscape architects are familiar with and use Computer Aided Design (CAD) systems. In most circumstances (and with compatible systems), they make it possible for designer and contractor to exchange files via e-mail with no loss in accuracy. With CAD, members of a project team can e-mail drawing files back and forth with everyone’s ideas and notes on separate layers, site surveys can be imported directly from surveyors or engineers and the designer can use the system to rough out difficult perspectives accurately before transforming them into illustrations. And because drawings can be shared almost instantly, CAD also allows you as a contractor to work with people who are far away, giving you access to a far deeper pool of designers. If you intend to set up electronic working relationships with designers near or far, it’s a good idea to ask them which system you should get for your operation. Many designers are quite knowledgeable in this realm and can help you select software that will suit your needs. In our business, we also sometimes act as an intermediary between a computer-savvy client and a contractor, sending drawings and sketches via e-mail or posting the latest illustrations on our web site so everyone can comment on them. This is the 21st century, after all, and there are myriad ways to use computers and the Internet to speed communications and reduce the number (and expense) of face-to-face meetings. — M.H. |

Our solution was to step the deck down around the pool, raise part of the bond beam, inset the spa into the other deck and finish everything off with natural stone, tile and plantings. The project is being bid right now: The client is happy – and so is the pool contractor who hired us, because he has the inside track on a project and design that expand his role and involve him in new areas of construction and new ways of generating revenue.

Landscape architects also can be of value when it comes to working with inspectors and government agencies. In our area of northern California, for example, two of the local design-review boards require fairly specialized drawings for approval, and this trend toward increasingly complex review processes seems to be gaining momentum around the country. One of our local boards, for example, requires full grading and drainage plans; another mandates irrigation plans that use reclaimed water.

When watershape contractors approach projects in these areas, they often call on us to prepare the plans and participate in the design process. This relieves them of the chore of preparing extensive plans they’re not set up to generate, and it also lets us work through the design with the client while the watershaper works out the logistics of construction and calculates costs.

At this level, it’s a coordinated, cooperative effort that keeps everyone focused on what they do best.

FINDING A COLLABORATOR

When we work with watershape contractors, I like to think that we’re all coming together to build something special and that everyone, from the designer to the builder and the service technician, is equally important to the project’s ultimate success.

By the same token, bad collaborations most often produce bad results. Crummy designs are often hard to build, the equipment won’t perform at peak efficiency and the watershapes are impossible to maintain. None of this leads to referrals!

For that reason, we’re selective in evaluating builders to install our work, and contractors should be, too, when choosing landscape architects to design theirs. It really is a collaboration, and if it works, a good builder influences the design as much as a good designer influences the construction.

| Another skill designers lend to the process is the ability to define relationships in space – as is the case in this sketch of a small waterfeature hidden in a small contemplative garden. The details, plans and logistics come later, once the client has decided which elements of the overall design should be pursued. |

Probably the most important step to finding a collaborator is conducting interviews with available candidates. Ideally, this will be a long-term relationship, so everyone needs to get along. Better yet, both parties should know each other’s work and perhaps have even worked together before or know people who’ve had good experiences with the other party.

As contractors, you also have the right to demand that any designer you interview has some familiarity with watershaping, knows something about how the equipment works and is up to date on construction techniques and materials. If you install koi ponds, for example, the designer must know about the nitrogen cycle, biofilters, dimensional requirements and other technical details. At a minimum, after all, the plans will need to show where the filters will be placed.

You also should discuss credit for the work and how it will be shared. On both sides, you need to talk about what happens if one or the other of you submits a project for an awards program or an article in the press and make certain that everyone involved in the collaboration gets credit.

In addition, it’s important to discuss money during the interview. Frankly, unfair fee structuring is probably the quickest way to ruin a designer/contractor relationship. Fees should be fair to both sides, and both sides need to be involved in setting the terms. If the designer thinks the fees the contractor wants to pay don’t justify his or her time, he or she won’t stick around long and you’ll have to go through the whole process again. In the same way, if you think the designer is using your money to buy an island in the Caribbean, that relationship won’t go far, either.

What’s fair? It all depends on factors too numerous to list here, but it’s something you need to work out early in the relationship in clear and unambiguous terms.

DEFINING NEEDS

Now we get to the important stuff – and some of the main reasons you want to talk to a designer in the first place.

Because ours is a visually oriented profession, you should make certain right away that the landscape architect or designer you are interviewing can actually draw – and make no mistake, not all of them can. You should insist on seeing graphic work, not just photos of finished projects, and you need to be sure they are proficient in drawing perspectives, because this is what clients have the easiest time visualizing.

| This is a case in which we remodeled a space after the pool had been installed, adding a cabana, new landscaping, new hardscape and revamped planters. This capacity to illustrate ideas in ways that help clients visualize the potential of a space is key to the services landscape architects offer – and a skill pool contractors should insist upon from their design partners. |

Good drawings and good client meetings are what make projects happen and effectively communicate what you’re proposing. But consider as well that landscape architects are not graphic designers: Where a graphic designer might make something look good, he or she isn’t trained to think in three-dimensional terms and can’t evaluate if what he or she draws can be built or if it will function once it is built.

Landscape architects bring more to the table. We’re trained to arrange outdoor spaces; consider proportion, style, color, forms and levels; evaluate drainage and anticipate construction and maintenance issues. To us, graphics are a means to an end, not the end itself, and you as a contractor need to keep that in mind in evaluating our skills with pencils.

|

Designer or Landscape Architect? As can be expected, designers come with differing levels of experience and training. The landscape field is no exception, but there’s more confusion here than in most other fields because not everyone knows the difference between a landscape designer and a landscape architect. As a rule, it’s tougher to categorize landscape designers. They may or may not have extensive training or experience, and they aren’t licensed by the state (unless they also have contractor’s licenses). None of that makes them bad or good – it just means that you have to review their portfolios carefully, make sure that they’re showing you their own work, and then make a decision based on the portfolio and the outcome of your interview. By contrast, landscape architects must qualify for the title. They normally have either a bachelor’s or master’s degree in landscape architecture along with several years of experience in a design firm, and they’ve passed a nationally standardized five-part licensure test. In most states, a state board similar to the pool-contractors board does the licensing and makes applicants take yet another test to qualify. In many states, a landscape architect’s license is required to design commercial spaces. The real confusion comes in states where anyone can call herself or himself a landscape architect. Others restrict the title but not the work, so a landscape designer can work on any type of project as long as he or she doesn’t actually claim to be a landscape architect. Other states have a practice act that prohibits any unlicensed person from practicing what it defines as landscape architecture. In other words, you need to know the rules in your own state to make the right decisions about selecting designers for your projects. And remember that this is a two-way street: Just as contractors seek out good designers, designers are always looking for good contractors who can execute their projects. Once you’re accustomed to collaborating, don’t be surprised if you get a great many referrals from the landscape architect or designer – projects to which you’d never have had access without connections you’ve made. — M.H. |

It’s also important in the interview to decide on the level of involvement you want the designer to have. Some designers have surveying equipment and can take care of site measurement, for example. They can also deal with base plan preparation, which is often just a matter of making a phone call to the architect to have a CAD file e-mailed to them.

The possibilities here run full spectrum: We can prepare quick sketches based on scaled base plans, create master plans or prepare detailed drawings for virtually every aspect of a landscape’s installation that doesn’t require an engineer. The only general rule is that the more plans you want, the more you’ll have to pay.

Lots of times, we get involved after some kind of base drawing has been prepared. Sometimes it’s just a quick site plan with some dimensions on it; other times it’s a sketch of a pool with the name of an architect who has the original CAD files. Whatever the source material, we start by transferring information to our CAD system, clean it up, plot out a base plan and then sketch out a concept or two.

Once we’re happy with the concept, we scan the drawings back into the computer and print them out so both contractor and client have copies. Once the client has made suggestions, we transfer the revised design back to CAD and produce a simple site plan with takeoffs for the installer.

Normally, the contractor presents these drawings to the client, gets their comments and brings everything back to us for final drawings. Because we have less involvement and no travel time, we don’t need to charge as much for our services.

FACE TIME

As an alternative to the arm’s-length approach just described, landscape architects can get much more involved. We can meet with the client, determine the layout and hand the resulting drawings over to you for installation. This happens when we initiate the project and hire a contractor; it also happens when a contractor doesn’t have the time or desire to get so involved in the design process and hires us.

| Making the big picture come together and work in clients’ backyards is often the result of profitable collaboration between a designer who sees the potential of the space in broad terms – and a skilled contractor who knows the practicalities of making watershapes work. When it all clicks, clients are delighted and everyone involved in the project reaps the rewards. |

In cases where we work for the client directly rather than at the request of a contractor, we provide an illustrated, scaled plan with text explanations of what’s already there and what we’re proposing, coupled with a perspective sketch or two. From there, we get feedback from the client and finalize the drawings in CAD and the job will go out to bid.

As required, we’ll prepare detailed working drawings that show dimensioned elevations and sections of proposed elements as well as planting and lighting plans, grading and drainage plans and dimensioned layouts. (There is also, of course, the X factor of design review boards that may require more extensive drawings.)

But we only need to go this far to make certain nothing is left to chance when a project will be put out to bid: Our list of required working drawings is thinned considerably if we have a solid working relationship with the contractor who will be doing the installation.

In other words, both designers and contractors have everything to gain from combining forces and making professional relationships work. There’s definitely time, effort and money to be saved in all directions.

Mike Heacox is a principal in Luciole Design, a landscape architecture firm based in Sacramento, Calif. He holds a bachelor’s degree in environmental studies from the University of California at Santa Cruz and a master’s in landscape architecture from Cal Poly, Pomona. Heacox and his wife, landscape designer Annette Heacox, founded their firm to promote fresh, new approaches to landscape design, using ideas gathered while living and working in France for more than five years and during their travels around the world. They advocate the mixing of state-of-the-art computer imaging and CAD techniques with hand-drawn illustrations to depict designed spaces before construction. Heacox can be reached via e-mail: mike@lucioledesign.com.