A Mexican Master

In his column for the November 2001 issue, David Tisherman mentioned a number of designers who have influenced him through the years. Even with my degree in landscape architecture, I have to concede that I was familiar with only about half the people to whom he called our attention.

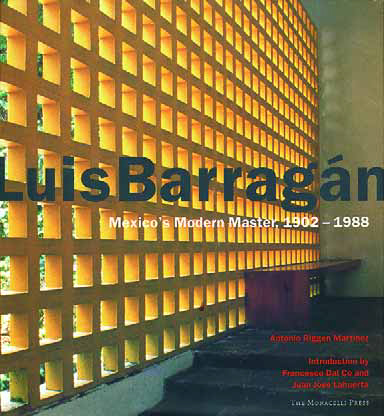

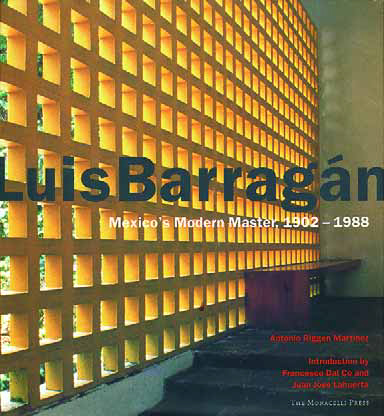

One of the designers I was unfamiliar with was Luis Barragan, so I picked up Luis Barragan: Mexico’s Modern Master, 1902-1988 (published by Monacelli Press Inc. in 1996 and written by Antonio Riggen Martinez) to find out something about him.

Barragan is now world famous, but that wasn’t always the case. In fact, it wasn’t until a 1975 exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art that he became widely known among designers in this country for his work in Mexico City and Guadalajara. His distinct, colorful style puts him on a plane with Ricardo Legoretta, another well-known Mexican modernist with whom Barragan briefly worked toward the end of his career.

Color and water were the two elements most prominent in Barragan’s work, and there were also periods in his long career during which he focused entirely on landscape architecture. His work is tough to describe, but it’s so distinctive that there’s no question of recognizing it when you see it.

The broad stucco surfaces and shapes are unmistakable, for instance, with their bright purples, reds, pinks and yellows. Then there are the massive, flat, shallow watershapes set adjacent to large walls whose vivid colors and angular geometry reflect and play on the water’s surface. And into these reflecting pools, which often measured in the hundreds of feet, he would send single, torrential sheets of water, creating sound and lending texture to the water’s otherwise calm surface.

Where art historians call him a modernist, Barragan thought of himself as a traditionalist and classicist who was simply translating existing ideas into a contemporary context. However he’s categorized, his career was very much influenced by what he saw and absorbed. He traveled extensively in France and Spain, where he was influenced by Le Corbusier, Ferdinand Bac and the other giants of 20th Century architecture and design.

He valued solitude and silence and spent a great deal of time contemplating his work – in some cases spending weeks or even months simply thinking about a project before committing any pencil to paper. When he did, he began with simple sketches that later took shape in the three-dimensional models he used in preference to flat renderings.

He also was known for making significant alterations to his design during construction – a practice that I’m sure was maddening to contractors but was necessary to Barragan because he believed that there were aspects of design that could only be truly mastered by working in the actual setting in three dimensions at full scale.

The text covers a large number of Barragan’s most famous projects, including the sprawling Egerstrom residence in Mexico City and the home of movie director Francis Ford Coppola. Also included are some of the large housing developments and the public spaces and parks that surrounded them.

To that extent, the text serves as a useful way to learn about this enigmatic master. But there’s a frustrating lack of insight into the reasoning behind Barragan’s work, perhaps because he preferred it that way. As he puts it himself, “Beauty is conquered not through reason, but by capturing the senses.”

So enjoy the intuitive quality and warmth of Barragan’s work. It may be difficult to describe or quantify, but it is utterly inspiring, provocative and evocative when experienced with open eyes and an open mind.

Mike Farley is a landscape designer with more than 20 years of experience and is currently a designer/project manager for Claffey Pools in Southlake, Texas. A graduate of Genesis 3’s Level I Design School, he holds a degree in landscape architecture from Texas Tech University and has worked as a watershaper in both California and Texas.