Images in Stone

Since the dawn of civilization, it has stood as the single most enduring of all artistic media: From representations of mythological characters and historic events to applications as purely architectural forms and fixtures, carved stone has been with us every step of the way.

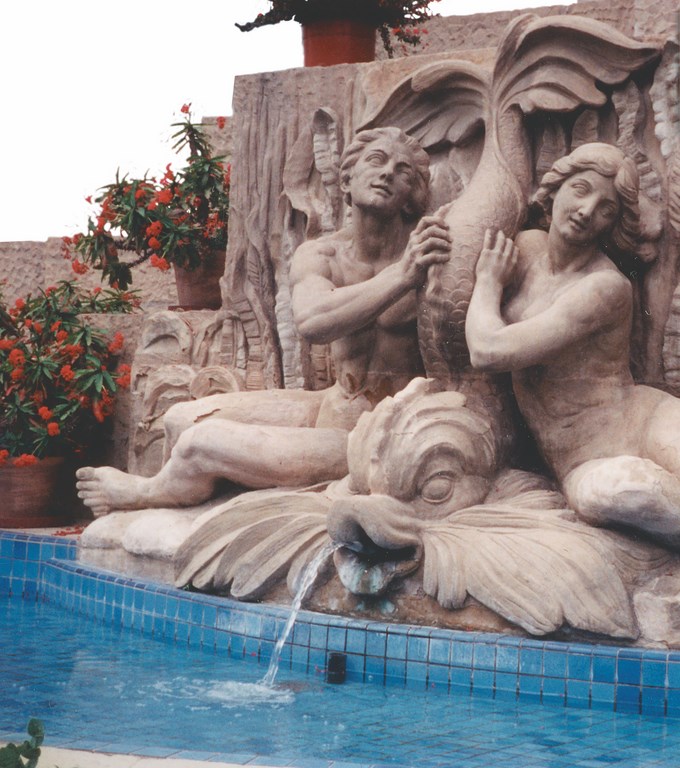

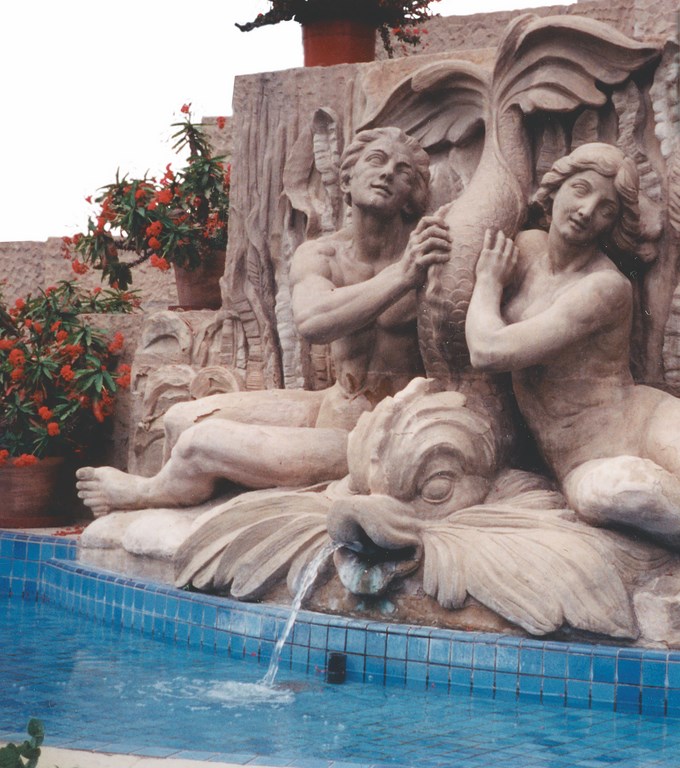

As modern observers, we treasure this heritage in the pyramids of Egypt and Mesoamerica. We see it in the Parthenon in Athens, in the Roman Colosseum and in India’s Taj Mahal – every one of them among humankind’s finest uses of carved stone in the creation of monuments and public buildings. As watershapers in particular, we stand in awe before the Trevi Fountain in Rome, the glorious waterworks of the Villa d’Este and the fountains of Versailles, three of history’s most prominent examples of carved stone’s use in conjunction with water.

But you don’t need to travel so far to recognize the stunning effect that carved stone can have within a space, aquatic or not. In fact, one need only consider how even the most modest use of sculpture or stone accents within an otherwise ordinary project can transform the “mid-range” into the “high end.”

To be sure, most watershapers have worked with stone in one fashion or another, typically as a decking material or as a finish for walls. It’s my view, however, that until you have used sculpted stone in one of its myriad forms, you have never truly used stone to its greatest aesthetic potential.

BODIES OF WORK

Whether we’re talking about limestone, sandstone, granite or marble, stone encompasses a certain, chaotic mixture of minerals that gives it an artistic coloration and texture that no painter could ever capture. And we accept and even celebrate its imperfections, which is, I believe, the truest testimonial to its remarkable aesthetic cachet.

If, for example, a stone sculpture is misshapen to some small degree as the result of an imperfection in the material or minor shipping damage, many people I’ve encountered will view the flaws as “character marks” that add to the appeal of a piece. By contrast, if a concrete structure is similarly uneven, it will likely be jack-hammered out and re-poured or recast in an attempt to achieve visual perfection.

It is this unique, “organic” quality of carved stone that draws us to it – and inclines high-end clients to pay large amounts of money to obtain it. The fact that sculpture is art permanently rendered in three dimensions lends it an allure that flatwork or less durable media lack. We’re captivated by the way light and shadow play on the features of a cherub or the petals of a rosette rendered in depth and detail. Whatever the form, sculpture creates wonderful focal points within a space and conjures a sense of elegance and class as well as connection to both the past and the future.

| Stone has been quarried and carved through all of human history, and there are places around the world where stone carving continues to this day as trade and craft. Parts of the process have been aided by modern technology, but mostly it’s hard, gritty, painstaking toil that eventually turns rough stone into works of art. |

What many people do not know is that stone carving is far from a dead art: There are still “Old World” craftspeople who work with stone as a medium similar to clay and spend careers toiling in the dust and grime to perfect their ability to chip, drill, chisel and polish stone into fine art. These stone carvers are often poor and uneducated, yet they create works that appeal to clients who are anything but.

On a practical level, this time-honored process can come with a hefty price tag, not only with respect to direct costs but also in the lead times required to obtain the product and the level of difficulty involved in commissioning the work and then safely installing it. Much more so than sculptures made of metal or clay, stone sculptures are heavy, dense and inclined to fracturing – and therefore difficult and expensive to quarry, carve, transport and install. Depending upon place of origin, you can wait months for carved stone pieces to arrive on the job site.

For all these reasons as well as simple matters of taste, stone carvings are not for everyone or every project. But there’s little doubt that when working at the upper end of the market, knowing how to obtain and use carved stone is a crucial arrow to have in your quiver. And that know-how begins with an understanding of the material itself.

KEY QUALITIES

Selecting the right stone for a given situation can be summed up in a few pairs of words: color and texture; weight and stability; time and money. Making decisions about all of these are essential in bringing stone to a project while keeping the client happy and making a profit in the process.

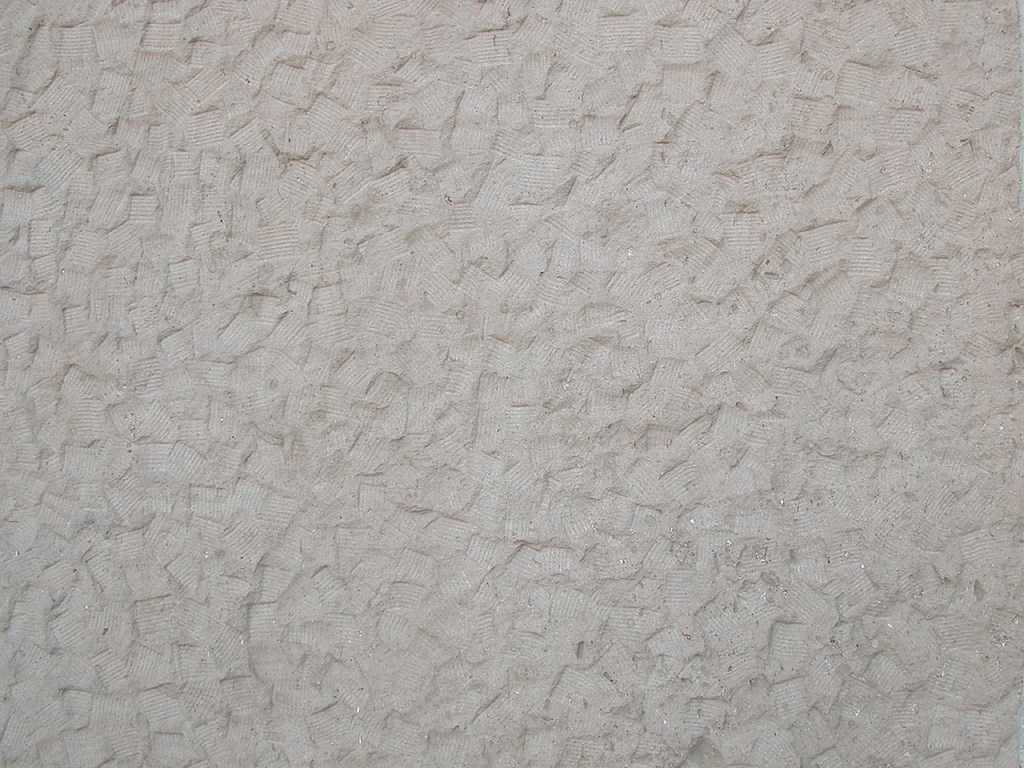

[ ] Color and texture: To a large extent, these aesthetic characteristics are of prime importance because they have everything to do with architectural style. Indeed, the colors and textures of certain stone materials are virtually synonymous with the settings in which they’re typically applied.

| Even flat surfaces can be carved – as seen here, where chisels have been used to work the surface and create artful texturing on otherwise unornamented planes of stone. |

When working on a Spanish villa, for example, a Cantera stone is usually the first choice, followed sometimes by a sandstone. This is so because the warm pinks, creams, beige and grays and soft textures of these materials are, by tradition, synonymous with the style. Similarly, a structure built in the style of a French chateau would find its best complement in the use of travertine or limestone.

The fact that certain stone types are historically associated with particular architectural styles leaves it up to the watershaper, landscape designer or architect to recognize those styles and, as needed, determine which stone types are most harmoniously used with which style.

[ ] Weight and stability: There are certain logistical issues that must be taken into account before you order anything – and most certainly before you begin the installation process. Weight, for one thing, can affect your ability to get a piece into place. Will you need a crane? Can the piece be moved by hand? Can a loader or forklift be rigged to set a carved stone fountain bowl or sculpted centerpiece in your basin of choice?

|

Reality Check In working with stone, you must always be aware that the sample you hold in your hand will look different from the stuff that shows up on pallets at the job site. The sample has been weathered, handled and had a chance to develop a patina – which will not be true of the freshly milled material hauled in by your stone supplier. I discuss this point with my clients over and over again: It’s a way to manage expectations, keep everyone on the same page and avoid disputes. — M.H. |

You also need to focus on the stability of the material and its ability to withstand the stresses of shipment and installation without fracturing. There are trade-offs here: Granite, for example, is a very stable but extremely heavy. Cantera is a much lighter, igneous stone, but it’s also known for its brittleness. These distinctions can be key factors in determining whether all goes well or you end up reordering a piece you have dropped, damaged, or fractured before getting it set.

[ ] Time and money: It can take a long time to obtain carved stonework – and, depending on the size and complexity of the piece, it can be quite expensive not just to acquire but also to ship and install. In many cases, the costs for the crane and labor needed to set the piece in place will be considerable on their own.

Many watershapers and other builders have been burned in the process by underestimating and underbidding the full cost of assembling stone creations and therefore have chosen not to work with them again. That’s unfortunate, because all it takes is a realistic assessment of these basic costs and clear communication with clients about how much money will be involved above and beyond the raw cost of creating the artwork and about how long the process can take.

I’ve found that under the best circumstances of timing, material availability and geography, carved pieces I order from Mexico for use in southern California take a minimum of four weeks to mine, carve and deliver. If I’m ordering limestone pieces from Italy, which is another place where stone carving still flourishes, I’ll be lucky to see the finished piece within three or four months, depending on the situation.

STONE SPECIES

As mentioned above, selecting the appropriate raw material for a stone carving in a particular setting is critical when it comes to consistency with a particular style.

In addition, knowing something about the raw material is just as important to managing the practicalities of acquiring the pieces you seek. Certainly, almost any stone can be manipulated and shaped as you wish, but certain stones – including slate and quartzite – have limitations that generally restrict them from use in carved-stone applications.

| Carved stone can be used in myriad ways in and around watershapes, from decorative accents, housings for fountain spouts or figurative statuary to fountain bowls, fountain surrounds, architectural details or stairway treads. Whatever the application, the play of light and shadow across carved surfaces – not to mention the special affinities between carvings, plants and flowing water – make powerful design statements in just about any setting. |

Indeed, knowing the nature of these raw materials and making the right choices among them is far more than half the battle. As I’ve worked with carved stone and studied its use throughout history, I’ve come to appreciate the characteristics of these stone types. There are many more than those listed below, but this basic list will carry you a long way:

[ ] Cantera and Adoquin: Found in central Mexico, these common volcanic stone types are actually quite similar. Cantera, the softer of the two stones, is the more common and can be obtained in colors from almost white and through a range of earth tones to almost black. Adoquin is a denser stone and therefore can be manipulated with finer detail and stability. Both are widely used in California and the Southwest.

[ ] Limestone (Italian and Mexican): Limestone has been our basic building block for thousands of years, and the fact that so many ancient limestone structures still stand today, with so many fine details intact, tells quite a story about it longevity. Known for its pure, creamy color, this is a dense, heavy stone well suited for carvings of extremely high detail and quality.

|

Water Tight? Stone does not typically hold water. The idea that you can take a series of limestone wall sections and cement them together for a fountain basin, for instance, is generally a bad one. While it is true that some stones are quite dense, most are porous to some degree and allow moisture to pass very slowly through the stone matrix. Stone pieces are also hard to butt up against one another, and custom dowels must be used with structural epoxy to join them together with anything approaching water-tightness. It’s also true that manipulating stone to meet hydrologic and structural needs can be extremely expensive and can never be guaranteed to work for the long haul. My preferred strategy when using stone inside a watershape is to build a masonry or concrete basin that can be plumbed, water-proofed and even veneered with tile before the stone ever arrives on site. This way, you can water-test the vessel and make modifications as needed. Now the stone is just an aesthetic element to be applied in a sealed, water-tight environment, and you will avoid problems down the line. — M.H. |

Mexican limestone, mostly from the Yucatan Peninsula, is less consistent in color and less dense than its Italian cousin and often contains fossilized sea life, a feature valued by some but seen as a blemish by others. These factors, as well as geographic proximity, makes Mexican limestone less expensive and easier to acquire than Italian limestone.

[ ] Sandstone: Many types of stone fall under this large umbrella. For the most part, these stones have soft, earth-toned coloration and smooth outer surfaces. They also have what the experts term “modular consistency,” which means that sandstone is, when carved, less likely to fracture than some other stones. (Where a material such as quartzite will splinter when carved with its grain, sandstone can be shaped in any direction.)

[ ] Granite: Perhaps most recognized for use as funerary headstones, granite is incredibly dense, very heavy and generally isn’t used for carving unless there’s a very good reason to do so. That said, it can be milled to great detail and will maintain that detail for thousands of years – but at amazing cost.

[ ] Marble: Some of the greatest of all art sculptures have been made of marble. It’s so durable and sought after that it’s even recycled, as is the case with the Trevi Fountain and many other monuments in Rome that feature pieces excavated from the ruins and mausoleums of ancient Rome. Its soft white surface often has colored veins running through it. One of the most expensive of all stones to have milled, it is also universally recognized as one of the most opulent of carved stones – an obvious sign of wealth and status.

[ ] Travertine: This ancient material is well known for its pitted surface and varied texture and has in recent years become the stone of choice for many designers and builders as part of the popularity of Tuscan-style architecture (despite the fact that what we see here has little to do with structures you actually see in Tuscany – but that’s another story).

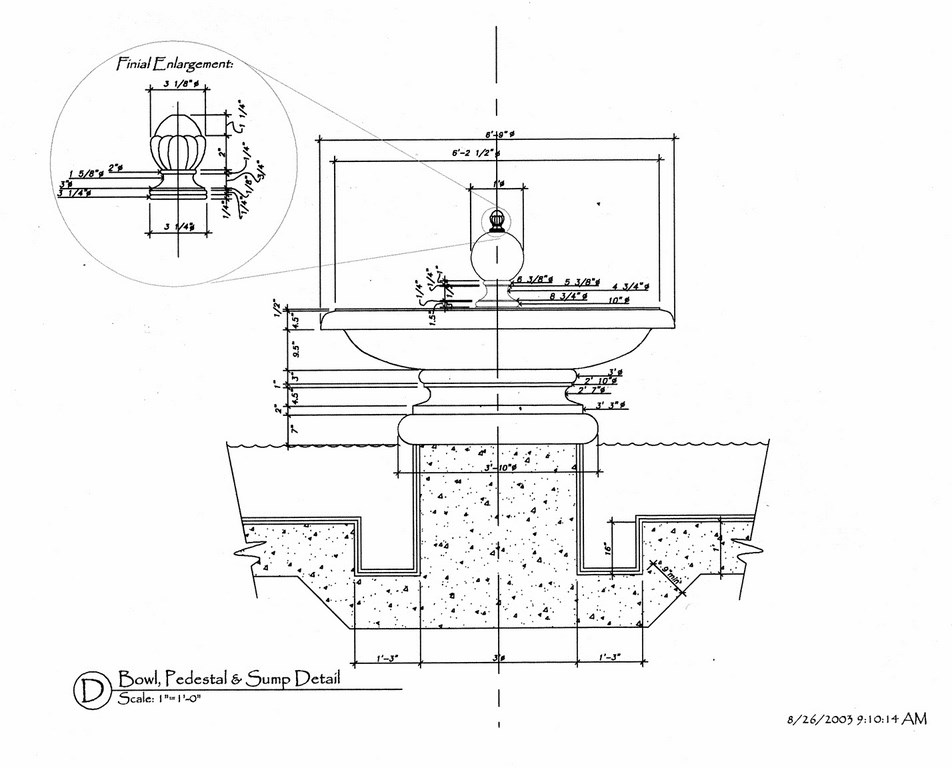

| Getting the desired result in commissioning a carved stone piece (such as a fountain bowl) takes communication of the clearest sort, down to accurately scaled drawings with measurements in fractions of inches if that’s what is required. Bottom line: If you leave anything to chance, the stone carver is left to “interpret” your needs – which, at long distance, is taking quite a risk. If you cover all your bases, however, the results have a fair chance of being right on target and will give you just the beautiful accent you were seeking for your watershape. |

Travertine is the material of choice in this Italianate style and it comes in white or with light-brown colorations. Travertine can come from Europe or Mexico, and the general rules that apply to the comparative cost and shipping of limestone apply here as well.

[ ] Slate: Although this stone is used for paving and veneers, it is seldom carved like the other stones discussed here. Because of its layered structure and mineralization, it is given to fracturing and is indeed splintered out of quarries for use. Through use of routers and grinding machines, however, it can be crafted into bowls and decorative pieces – but the result is a product that is extremely fragile.

SPECIFIED DESIGN

Once you determine that you’re going to use carved stone, you then need to pay a great deal of attention to communicating the shape and dimensions of the pieces you want to those who will do the carving.

Potential stone shapes are basically unlimited: Whatever you can imagine can usually be carved, but if it hasn’t been done before or you want something even slightly out of the ordinary, you need to be able to tell the carver, in very precise terms, exactly what you want.

|

Horror Story Most large projects involve their share of problems. With one of my largest, the Cima del Mundo project that has been covered extensively in WaterShapes, I had ordered a custom-designed, custom-cut, nine-foot-tall Cantera stone fountain for the central courtyard. I designed it, ordered it, paid a 50% deposit and waited eight weeks only to open a monstrosity on the job site. A basketball-sized chunk had broken away from the bottom bowl and had been patched with colored cement. Other fist-sized holes hadn’t been patched at all and, topping everything off, the camel-colored stone I had ordered came through as pure white. I refused to show my client the fountain and made profuse apologies while taking blame for the whole disaster. I also went looking for another supplier. After some digging, I found Sean Nelms at DeSantana Stone in San Diego, Calif. He handled the task with military precision, quickly developed shop drawings from my conceptual sketches, delivered a replacement in a matter of weeks and literally saved the day for us: If the central courtyard fountain had not been pulled off to perfection, we would have had an extremely displeased client. This experience reinforced my sense that you need to deal with true professionals if you seek to provide your clients with top-flight results. — M.H. |

This is very important: If you want the craftsperson to get it right, you must provide exact design specifications, such as those found in the diagram seen just above for carving a limestone piece. This carving detail has a tolerance of less than one eighth of an inch – and that level of accuracy is expected in the finished, delivered product. (And know going in that, even when you provide an adequate level of detail, there can still be problems such as those described in the sidebar at right.)

These problems have a natural tendency to arise because working with stone can be an imprecise art. The raw material, the skill of the carver and unforeseen complications in transport can all influence results. The best advice: Do your homework, find as professional an artisan as possible and don’t be seduced by low pricing that can lead to more headaches than you could ever imagine.

If you simply send an e-mail with an attached low-resolution photograph to a stone carver and ask him or her to make it, what you’ll get is an “interpretation” of the photo – and you can rest assured that what shows up weeks or even months later will only vaguely represent what you really wanted. Your best bet is to treat each carving as respectfully as you would a custom, structural-concrete detail and specify everything possible down to the finest detail.

If you do so, your chances for aesthetic success multiply – and you’ll end up installing a sculpted work of art that brilliantly complements your work as a watershaping artist.

Mark Holden is a landscape architect, pool contractor and teacher who owns and operates Holdenwater, a design/build/consulting firm based in Fullerton, Calif., and is founder of Artistic Resources & Training, a school for watershape designers and builders. He may be reached via e-mail at [email protected].