The Trouble with Liners

As modern building materials have been developed, we humans have been remarkably proficient at applying them in ways that go well beyond the vision of their inventors. Such is the case with roofing membranes, which now are widely used as liners for backyard streams and ponds.

It’s understandable that landscape designers and contractors have taken to these rubber liners. After all, they make pond and stream construction inexpensive and easy. But from the perspective of the Japanese gardener or quality watershaper, convenience and affordability alone do not qualify a material for use. Instead, standards of durability and enduring beauty must be applied.

In that light, it quickly becomes apparent that rubber liners have numerous drawbacks when it comes to creating quality ponds and what are known to Japanese gardeners as yarimizu, or winding streams. Most of these problems emerge only with time, and because they are not always immediately apparent, many quality-minded people have been lulled into a sense of security and comfort with liners that ultimately proves detrimental to the environments they’ve created.

It’s my contention that when you strive to create enduring works of art – which is presumably what quality watershaping is all about – then using a material that is impermanent, subject to punctures, difficult to repair, and completely lacking in structural support is ultimately self-defeating. In the long haul, rubber liners don’t get the job done. Concrete, I’d argue, is a far better choice.

BASIC NATURE

Obviously, there are going to be those among you who will disagree with my position. Even the advocates of liners, however, are familiar with the shortcomings of the material. For starters, liners are thin and pliable and don’t offer much by way of resistance to punctures. Yes, they perform well in holding water when handled and installed with care, but it doesn’t take much experience to know that leaks are a very real possibility, not only during installation but also in the weeks, months and years that follow.

To be sure, there are several different liner types and grades and mil thicknesses out there, and some are more durable than others. Many have projected life spans that exceed 30 years – a significant improvement over products that were offered not too many years ago. But if you think about it, three decades isn’t long at all. Consider our common worlds of art, architecture, and landscape gardening. How old is that painting on the museum wall? How old is the house you live in? More to the point, how old are the noteworthy gardens in your region?

I’d argue that 30 years, in the case of something such as a painting, a house, or a garden, is laughably far from permanent. Compared to a quality watershape such as a Japanese garden, 30 years is a mere “blink of an eye.” In Japan, for instance, are hundreds of gardens more than 300 years old – and some that are 800 years old. From that perspective, it’s not the waterfeature’s lifespan that matters, but rather the fact that it has a defined lifespan at all!

Boulders don’t have lifespans, nor do earthen berms or streambeds. In an art form that should be (and very often is) meant to last for centuries, some materials – stone, rock, water, trees and earth – are well-suited to go along for the ride. Rubber liners, I’d say, are simply not up to the task.

Creations that are beautiful, that stand in defense of quality, that represent doing what’s right and performing a task well are artifacts that transcend age or life expectancy. If you care about the permanence of your work, why would you ever settle for using a material that is, by nature, so flimsy and impermanent?

DON’T DESTROY THE ART

Among the several bones I have to pick with liners, the most important is the fact that replacing a damaged liner almost always involves ruining the environment the liner was meant to sustain.

Liner replacement is a horrible process: It means ripping out everything set within or atop the liner as well as plant and stone material immediately around the liner. That may not be a big problem for a low-end backyard pond that was built from a kit in a few hours, but it should be completely unacceptable in a high-quality garden – or any other quality watershape environment, for that matter.

Speaking specifically of Japanese gardens, the design and construction phases are just the first steps in a long journey. The rest of the journey – say, 299 of the next 300 years – consists of guiding, grooming, enhancing and improving the garden.

Such gardens are an art form that is created and unfolded over decades, generations and even centuries. Much of the work that’s done consists of carefully pruning trees and other plants, making small adjustments to stonework and performing regular maintenance by weeding and sweeping. It is this effort, which takes place long after the “construction” has been completed, that ultimately determines the success or failure of a Japanese garden.

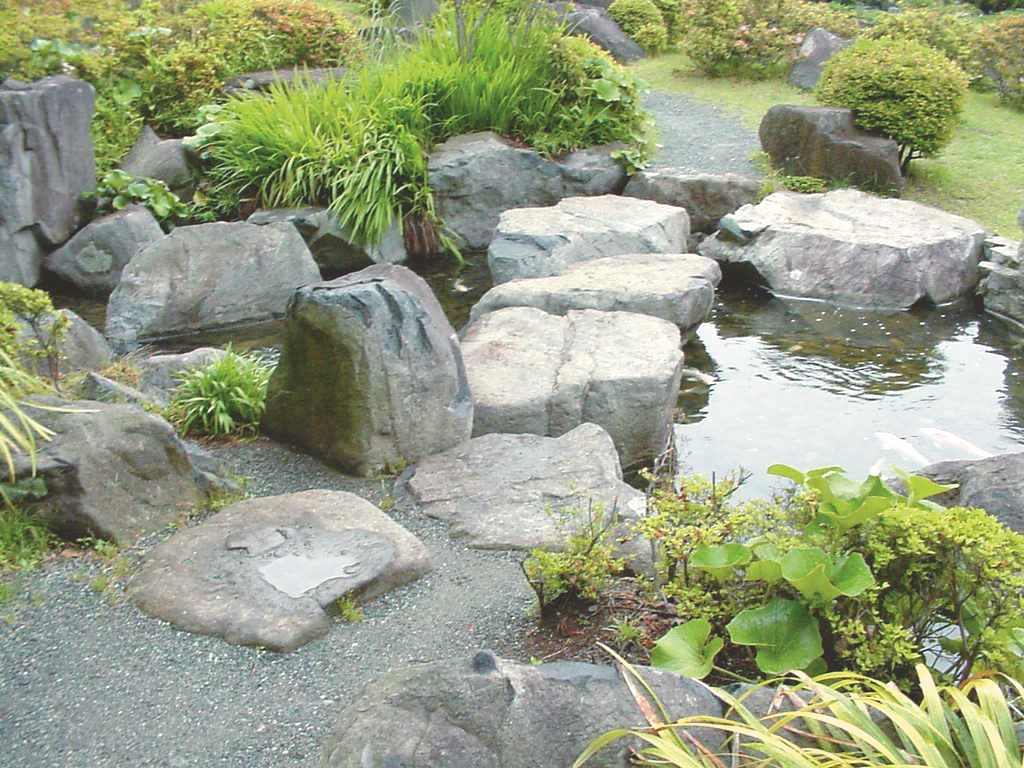

| One of the key problems with using a liner is that repair of any serious leak would involve huge disruptions to (and perhaps the complete destruction of) settings such as these. Some of the boulders seen here are quite large and have been placed, adjusted and tuned to their surroundings with painstaking care – so much so that it seems irresponsible to place them over a material that at best will need to be replaced in a matter of decades. (Photos courtesy Journal of Japanese Gardening) |

Imagine being the owner of a beautiful garden and Koi pond: For 30 years, you’ve poured heart and soul into pruning trees so they cascade down over the water, tuned the waterfall so it sounds just right, and carefully swept and weeded the moss beds. Now, just as your garden reaches a state of near-perfection, the liner starts springing leaks. Some minor patches can be made if the leaks happen to be in accessible places, but inevitably, the first leak is just that, and more of them develop to the ugly point where ripping apart huge portions or even the entirety of the garden is the only option.

To replace that liner, you’ll have to lift up the multi-ton boulders along the edge. And to do that you’ll likely need to bring in heavy equipment, which means the disruption won’t be limited to the watershape’s footprint. There’ll be a pathway for the machinery, a place to store rocks and working room around the vessel to allow for installation of the new liner. In other words, to replace the liner, you’re going to completely destroy the pond and much of the rest of the garden in the process. The wrong-headedness of this should be self evident: The pond is the artwork, not the liner. Why destroy it?

If someone does decide to destroy the art just to replace the liner, he or she ought to be forewarned that re-installing those plants and boulders is no snap. In the art of Japanese gardening, for example, setting edge stones is a real art, and there aren’t many people who know how to do it correctly. If the garden was created using traditional edge-setting methods, you’d need to bring in a specialist to rebuild the space. All in all, replacing the liner in this way is analogous to tearing down an entire house just to replace leaky copper pipes in the basement.

CONCRETE AND CLAY

It’s my view that there are far better materials for waterproofing ponds, streams and cascades.

The famous, centuries-old ponds of Japan, for example, are all lined with clay – malleable, waterproof, self-sealing (to a certain extent), inexpensive and reparable without the need to tear everything apart. Of course, leakage isn’t a huge concern in those venerable bodies of water because they are typically fed by nearby streams or rivers, and a certain amount of leakage is expected. The water is free, and it flows over the waterfall, through the garden pond and then merrily on its way downstream.

In a way, traditional stream-fed gardens were much easier to execute than today’s systems, where water needs to be purchased, retained, filtered and then re-circulated. Most of these modern waterfeatures are what I call “self-contained,” which makes them more difficult to execute and more expensive.

Clay still might play a useful role in larger modern waterfeatures, but for backyard ponds and swimming pools I recommend steel-reinforced concrete – gunite, shotcrete, poured in place or hand-packed – as the best way to create permanent high-quality pond and stream structures. When properly engineered and installed, these structures can last centuries without disintegrating the way liners inevitably will.

| It’s odious enough that pulling up a leaking liner to replace it will compromise the water environment and its tailored edges, but the fact is that the planted areas around the water will also be upset by earth-moving equipment, the need to store displaced rocks and a likely lapse in care. For watershapers with an open-ended sense of the future of their work, the choice should always be for more permanent underpinnings. (Photos courtesy Journal of Japanese Gardening) |

Proper engineering and installation are obviously important if one of the goals is permanence. After all, substandard concrete vessels will break apart and fail just as miserably as any rubber liner will. But for the most part, properly-engineered concrete will hold up, and it can be repaired without disrupting the entire environment if minor leaks occur.

This is why I believe that most landscapers and pond builders can learn a great deal from swimming pool builders. The way I see it, the pool industry has been working for decades with technologies and techniques that can prove useful in containing, treating and recirculating water in our naturalistic environments.

Swimming pool builders work every day with hydraulics, structural issues and geotechnical challenges that come with all man-made bodies of water. I’ll go so far as to say that combining the technical knowledge of the swimming pool industry with the aesthetic sensibilities and craftsmanship of Japanese gardening is the key to a future filled with naturalistic watershapes of breathtaking quality – and ponds or streams that are beautiful to look at while being structurally sound below grade.

ENGINEERING ANGLES

In dismissing liners, I’m not saying that rubber liners leak while concrete structures do not. Gunite and shotcrete structures do indeed develop leaks under a variety of circumstances, but as was just mentioned, they generally can be repaired in place. In addition to this important trait, concrete offers a number of other advantages.

For example, reinforced-concrete vessels can be engineered to provide a level of structural support for the large multi-ton boulders placed along their edges. It’s the same load-bearing idea as building a house on a foundation or placing a bridge on concrete piers. Without the proper engineering support, any serious structure is doomed. By contrast, homes and bridges built on proper foundations have lasted for centuries.

Multi-ton boulders of the sort used in naturalistic watershapes require adequate support if they are to remain in place for the long haul. The fact is that soil moves, heaves, compacts, slides and expands, and any boulder set on a liner supported only by the soil is certain to move. That can be a huge problem if you’ve gone to the effort of sculpting a garden. By contrast, concrete substructures can be engineered and built to support a boulder of any size – with little or no movement at all – for generations to come.

| As a Japanese gardener and watershaper, I’d like to think that these people, should they be fortunate enough to live so long, could return to this space in 40 or 50 years and recapture the emotions and romance of the moments they spent together on this graceful bridge. To me, to offer them anything less than that opportunity seems inadequate – and a betrayal of all the work that goes into establishing such a setting. |

To be sure, watershapes made with reinforced concrete are typically far more expensive than are those made with unsupported liners. For those who aim to provide customers with cheap ponds and streams that are not meant to last forever, rubber liners might be the option of choice.

But for those of you who are concerned instead with creating works of art among your gardens and watershapes, I encourage you to think beyond the standard lines of demarcation within the trade, embrace the materials and technologies used by quality-minded swimming pool builders and insist on using reinforced concrete as your watershaping structure of choice.

The two structures – a natural-looking fish pond and a concrete swimming pool – might look a little different and might serve slightly different purposes, but they both need to contain water reliably and support the necessary engineering load. So below the water’s surface and beneath the edges, the two structures should be much the same.

I’ll even go so far as to say that a high-quality garden pond or stream should be constructed of nothing less than the same materials used in a quality backyard swimming pool. In fact, natural ponds and streams might even need to be more sturdily constructed because of the vertical waterfalls and multi-ton boulders.

CONVERGENT PATHS

Culturally speaking, Japanese gardeners and high-end landscape designers live in a world that is indeed far removed from the one occupied by swimming pool contractors. The former have been trained to create beautiful, highly aesthetic works of art in ultra-naturalistic settings, while the latter most often make vessels that have an architectural or industrial look and make only lagoonish gestures toward the natural.

In that distance is opportunity, and I see both sides of the watershaping industry benefiting from finding a workable middle ground. Pool people, for example, stand to benefit from becoming familiar with the refined design sensibilities of landscape artists, while landscape people can gain much by embracing the hard realities of inground concrete structures.

Watershaping is the bridge that brings us together in ways that neither group probably ever considered possible. This notion of using concrete instead of liners to create more permanent structures is a prime example of where the convergence could and should begin.

Douglas Roth is publisher of The Journal of Japanese Gardening. Widely considered to be America’s leading authority on Japanese pruning techniques, he is a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Md., and served for six years as a naval officer in the Philippines, Hong Kong and Japan. He resigned his commission in 1988 and established The Isshiki Zoo, an English language school for children in Hayama, Japan. After passing the National Language test, he began a five-year gardening apprenticeship in Kamakura and became the first foreigner qualified to practice gardening in Japan. His company, Roth Tei-en, designs and maintains Japanese gardens throughout North America. He holds a degree in mechanical engineering and worked as an engineer while in the Navy. He is also a certified arborist and a member of the International Society of Arboriculture.