Standing Tall

The fire came swiftly, sweeping through the dry, late-summer undergrowth, and the land was quickly blackened and denuded. A month later, the rains came, hard and lashing, and rivulets of water ran down the hillside. Torrents of mud and stone ground away the soil and washed out the base of a tree that happened to be in the way.

The tree fell. Branches became splinters on the ground. The noise the tree had made as it fell was intense: a cracking and groaning sound followed by crackles as limbs snapped against still-standing trees. Now it lay there, its roots all but pulled from the ground.

Ten years passed, and as the tree’s bark rotted, small saplings had begun to grow from its base. The creek ran close by, gurgling and never-ending, its water wending its way among the rocks and other fallen trees toward the ocean just half a mile away. This tree would serve a purpose in its death: In my work as a sculptor, I seek out redwood logs such as this one.

FORMS IN WOOD

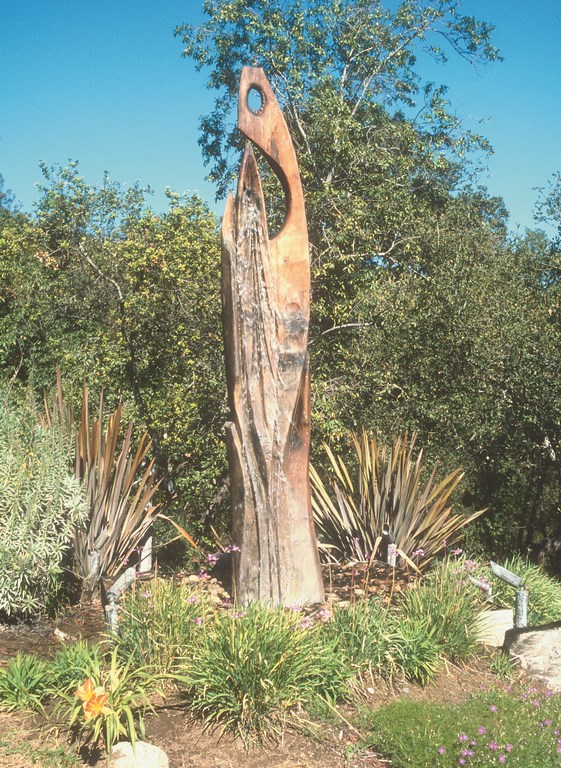

I’ve worked with downed timber for 30 years, seeking the inherent beauty of its grain and prizing the durability of its wood. My works are not the traditional chain-saw forms you see so often along country by-ways – the ubiquitous bears, or the seagulls on posts. Instead, I create redwood waterfeatures that have a distinctly contemporary feel to them.

As far as I know, these unique abstract/contemporary sculptures are the only ones of their kind – and testament to the fact that I never grow tired of the beauty and delight that can be found by combining water and wood.

I started out as an engineering student but quickly switched over to pursue a metal-sculpture major at California State University, San Diego. My fondness for the naturally sculpted driftwood I saw on the beaches of the Pacific Northwest led me to turn my engineering skills and an emerging appetite for artistic expression into sculptures that imitated natural forms – birds, dolphins, seals, and whales.

But occasionally, I put together the occasional copper-and-wood waterfall, and ultimately found myself following a new and uncharted path. I was enabled to follow that course courtesy of The Hawthorne Gallery, established by my brother-in-law, Gregory Hawthorne, in Big Sur, Calif. The gallery set me free from the usual constraints and mindsets and gave me liberty to design and create without much distraction.

Our first big waterfeature was a result of happenstance. A client in Taipei had ordered a large sculpture, part of which was to be several redwood columns. Economic setbacks led to cancellation of the project, and I was left with five huge columns of clear, old-growth redwood – so I ordered a chain saw with a six-foot bar and called up my youngest son, Terry.

As our work progressed, we were always thinking sculpture not waterfall, but for some reason we found ourselves being drawn into discussions of the possibilities. It was no more than talk until a year later.

Greg Hawthorne, who is an artist as well as gallery owner, has been creating and installing large waterfeatures in steel and granite for some time and had been asked by the Ventana Inn & Spa in Big Sur to design three water sculptures for the grounds. The Ventana stands in the wilderness among redwood groves, and Greg suggested that redwood waterfalls would be more appropriate. He called me, and we discussed the feasibility and durability of such a structure. Before long, we were engineering the pieces.

A dozen projects later, these graceful watershapes are still evolving, but certainly not without a fair share of challenges along the way. As with any sculpture in any medium, there are certain difficulties to overcome or problems to solve, not only aesthetically but practically. In the case of our watershapes, these included weather variables, safety precautions, wiring, plumbing and lighting – all issues that we’ve addressed and refined through the years.

GETTING TOGETHER

Greg Hawthorne’s role in all of this is crucial. Clients who come to his gallery often have unique ideas, and he does an incredible amount of preliminary work in helping those ideas take shape.

He often visits sites and discusses clients’ specific needs, and at the same time he’s carefully analyzing the situation and developing important information about the potential piece: how large, how tall, how much water, how loud the sound should be, whether the sound is for ambience or to establish a white background noise, and anything else about variables that may come into play.

|

Fading Away or Knots What about the durability of the wood in connection with water? That question often arises in our conversations with clients, and it’s a concern reflected in the fact that there’s no longer much of a market for wooden boats. I can name several instances, however, where wood is not only the most beautiful option to be used in connection with water, but it’s also the most practical. After all, many of our homes have wood siding or shingles and are surrounded by wooden fences and decks. In all such matters, the quality of the wood and the way it is treated are critical. To start with, the woods I use – redwood and cedar – are unusually durable. It can take up to 500 years for a five-foot-diameter section of redwood to completely decompose, the culprits being primarily fungus and bacterial action. To control both fungus and bacteria (and to take care of most mosses), all it takes is using slightly acidic water. Beyond that, the sculptures can be pressure-washed perhaps once a year and re-oiled as with a deck – although you’ll lose a little detail each time. Another way to forestall deterioration is to keep the wood from drying out, which is why I seek in my sculptures to start the water flow at the top to ensure that the entire piece is evenly hydrated. For all that, wood is a natural material, and a steady flow of water will alter its surface over time. As much as I set pieces up and try to manage the way the water flows, through the years the water will do what comes naturally and create its own courses. — S.K. |

He considers issues that clients might never see, such as wind exposure, appropriate plantings, debris levels and their effect on the system, the nature of the soil that will support the structure and any special maintenance the wood surface might require given the specific conditions he encounters. As I mentioned above, this arrangement frees me to focus on working the wood itself.

My creative process begins once I’ve procured the log required by the job as specified. I never go out and cut living trees, instead seeking out fallen timber. For one thing, it’s lighter – and in most cases the “curing” process has been completed. Redwood and cedar are my woods of choice, basically because of their excellent weathering properties. In some cases, the logs I’m dealing with weigh in the tons and must be handled very carefully – especially after the carving has been completed.

All of this requires big-scale equipment and a good deal of time.

I prefer to design the piece with the log standing up, starting on one side with a lumber crayon and working my way around the log. Once I’m satisfied with the design, I’ll lay the log down to carve it with a variety of chainsaws, chisels and other equipment to get the rough shape and then polish the surface.

When asked how long it takes to make a sculptural wooden watershape, I’ve been known to say that the process has taken me more than 20 years because it’s taken me that long to collect the tools and the knowledge – and for my son to grow big enough to help me.

Once the primary shaping work is complete, I spend a great deal of time just looking at the polished surface of the wood and evaluating and re-evaluating the way water flows over it: I know from experience that the smallest crack or bump can send the water off the mark and beyond the desired containment area. This also where I must be at my most creative, because the piece inevitably has changed in small ways from my original concept as a result of defects in the wood or the way the water actually wants to flow.

WORKING ART

It’s not a passive process: I definitely have certain flow patterns in mind with each sculpture and seek to capitalize on them.

I’ll sometimes carve a channel with my chainsaw as the water flows, making adjustments until I see perfection. There is much I have learned through trial and error, and I’ve used many logs as practice pieces; these days, however, I am reasonably confident that I can achieve the effects I’ve envisioned myself getting out of these wood surfaces.

Somewhere during the process, I’ll figure out which is the front of the piece. Moving to the opposite side, I’ll carve a groove about three inches wide and six inches deep and then chisel out a plumbing chase. The piece that’s been chiseled out is then trimmed down and wedged back in to hide the pipe.

Depending upon the size of the piece and the amount of water to be thrust upwards, I’ll sometimes lay in a piece of copper to cover the pipe’s top outlet, effectively forcing the water downwards and outwards over the top of the sculpture. Other times, I’ll carve out a small reservoir at the top of the piece to allow water to pool and then flow out through cuts and incisions I’ve made in the top of the piece, creating a relatively even flow over the entire sculpture.

My goal in all of this is to encourage viewing of the totem from all angles.

Once the piece is close to being finished, I make cuts at the base to create a square plug that will fit into a frame made (usually) from treated three-by-six-inch beams that serve to position the totem to the middle of the basin. More often than not, a double box in the middle of the frame will hold the entire sculpture steady; if it’s needed, however, the assembly can be bolted to stabilize it further.

The entire framework is then covered with a latticed steel grate over which either wood chips or small pebbles or stones can be placed for a more finished look. Leaving a small access door to the pump and valve makes adjusting the flow and basic maintenance and cleaning much less of a chore.

Jigsaw

The Jigsaw totem is so named because of the amount of carving it took to get the water flowing down the center of the piece in just the way we wanted. Ultimately, the babbling-brook sound thrown off by the wood makes up for the work involved.

This piece also uses stone in the form of a large granite base with a hole in the middle through which the water escapes and in which we set the one-inch feed line. For the moment, this sculpture sits next to the entrance of the Hawthorne Gallery, encouraging visitors and clients to see the great potential bound up in combinations of water and wood.

Triad & The Ancient One

As one enters the Ventana Inn & Spa from Highway 1, the road splits around The Triad. In music, a triad is defined as a chord of three tones. In essence, the music coming from this sculpture introduces visitors and guests to the property.

The sculpture itself has a totem feeling, but it is energized by a cascade falling freely around each piece and its channels and pockets. The sculpture’s impressive 16-foot height adds to the power of the piece as a whole.

Installation was relatively simple. Greg Hawthorne designed a six-by-six-foot basin, two feet deep, that he countersunk into the ground. We used a forklift and several able bodies to position the completed pieces and then dropped them carefully into slots I had made.

The next piece – The Ancient One – is positioned at the entrance to the lodge at Ventana. Positioned on a footpath and adjacent to the spa, we set it up to have a subtle-sounding waterfall created by hollowing out the bottom portion of the piece. The water drops three feet after flowing smoothly over the top lip of the sculpture, and the entire composition has a primitive and timeless feel – almost as if the water had done all the carving.

Wings

This installation, one of our most recent, sits on a private property in Big Sur and demonstrates the “evolution” of this art form with respect to complexity and sophistication.

The piece features two falls that cascade down the center of a hollow section of carved red cedar. Two 1-1/4-inch lines carrying the water up through the piece are hidden behind carved wooden slats capped with soapstone, which was used in several other areas to balance the design. We also added a copper screen to catch needles from the overhanging trees.

Special effort was required in placing this piece amid the large expanse of lawn. The open center of the piece allows a view of the Pacific Ocean: As we moved the piece into position, the client – also an artist – observed the process and helped us fine-tune the placement. A late observation, also by the client, noted that with a larger water flow, what had been a small ripple in the tank could become a major water element at the base.

We gratefully acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Toby Roland Jones of the Hawthorne Gallery, Big Sur, Calif., in preparing this article.

Steve Kuntz is a wood sculptor who lives and works in Coquille, Ore., where he searches local forests and riverbanks for fallen trees and driftwood that he uses in his unique modernist sculptures. His work focuses on the creation of free-standing and wall sculptures for interiors as well as on wooden watershapes. He and his wife, Lisa Hawthorne, an award-winning cloisonné jeweler, are both featured artists at the Hawthorne Gallery in Big Sur, Calif. Theirs and other one-of-a-kind pieces can be seen at www.hawthornegallery.com.