Powers of Observation

Most people move easily through the world, enjoying the scenery without really thinking about what makes those surroundings visually appealing (or not).

Science tells us that the human eye can see about seven million colors and that our minds instinctively perceive depth and dimension. This visual capacity enables most of us to move around without bumping into things, some of us to swing at and somehow hit a golf ball and, in the case of a beautiful garden (we can hope), all of us sense pleasure and maybe a bit of serenity.

In contrast to these casual observers, we as designers must understand the nature of visual observation in a more sophisticated and deliberate way.

Through the years, clients and friends have asked me how I developed my design skills. I usually start by admitting that I have a great memory for the botanical names of plants and how they look and work in gardens and mention that I have reasonably strong drawing skills, all of which they understand immediately. They also get the fact that, as with any set of skills or form of professional acumen, years of practice simply make some things start to come naturally.

What hasn’t come naturally, however, has been my ability to see things in a particular way that enables me to dissect various portions of a visual plane, for example, or take any number of selections from a large palette of plants or hardscape elements and assemble them as visually balanced designs that appeal both to me and my clients. These skills, I explain, are learned over time and are constantly challenged and honed by looking at environments through a trained designer’s eyes.

ALL EYES

In my case, it’s taken years of observation to develop an “eye” for what works and what doesn’t. Through that learning curve, for example, I’ve become able to see which colors or hardscape materials go together (and those that don’t). The trained eye can almost instantly see which plants work together in a cogent design scheme and those that disrupt the sense of continuity in a given setting.

To be sure, these subjective determinations depend upon an individual’s sense of what works and what doesn’t. In some respect, this is about an intangible quality that can be called “aptitude” or “talent,” but it’s also a distinction that makes room for all of us and our idiosyncratic, individualized ideas and outlooks on the world around us.

Separated from talent and a welcome diversity of tastes and perspectives, however, is the fact that developing an eye for design and visual detail is something that can be learned. Every one of us can enhance the way we see and perceive our surroundings and can nurture our observational prowess as a skill that ultimately will lead to an ability to develop designs composed of elements that work together in harmony. In the world of exterior design, that means looking at the world around us from a variety of perspectives that would be lost to the casual observers we encountered at the outset of this article.

Also lost to many observers is the fact that landscapes are incredibly dynamic canvases: They constantly change with the time of day and year, so a garden in summer that is awash with color, flowers, insects and other creatures will settle into dormancy, lose its vibrant colors and surrender much of its visual appeal during the winter. The following summer, that same garden will be different than it was the year before – perhaps a plant will have died over the winter, or maybe something was added in the spring or grew to change the overall visual plane and our perception of the space.

For their part, most people outside the exterior design professions (including most of our clients, unfortunately) will tend to see a garden the same way every year. As designers, we don’t have that luxury of allowing ourselves to relax and simply live with any landscape: Instead, it’s our job to observe and anticipate changes and respond to them either by incorporating what we see into our design work or, in the case of a completed garden, by helping a client to understand what they need to do to maintain the visual balance we originally defined.

The most important thing to understand here is that to develop the observational skills needed to see things in this deliberate way, we need to get down to basics and begin by looking differently at simple objects.

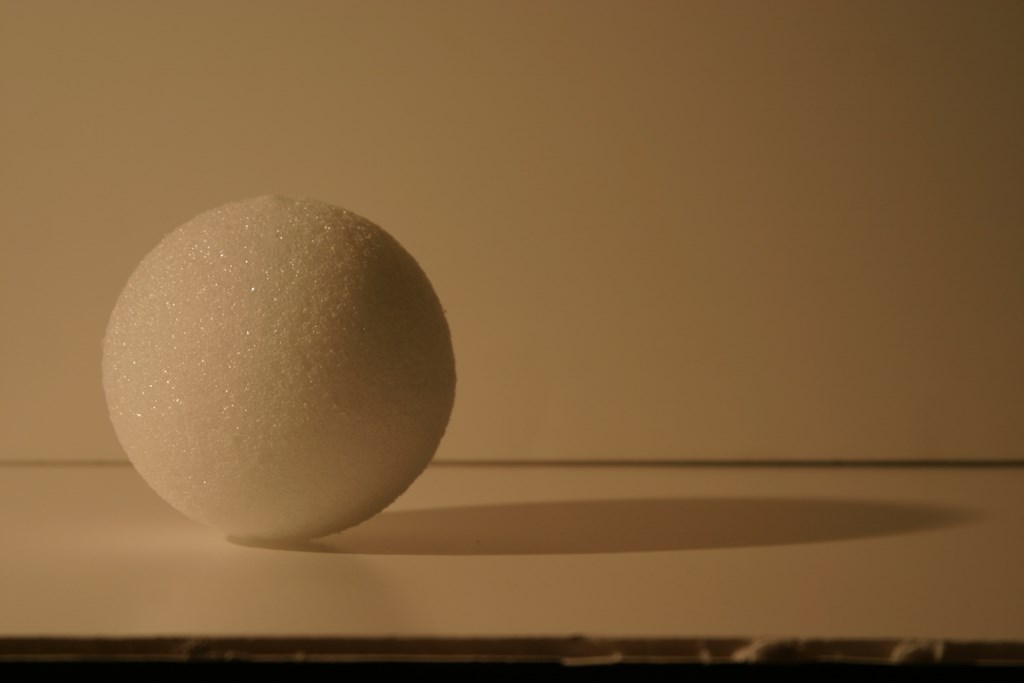

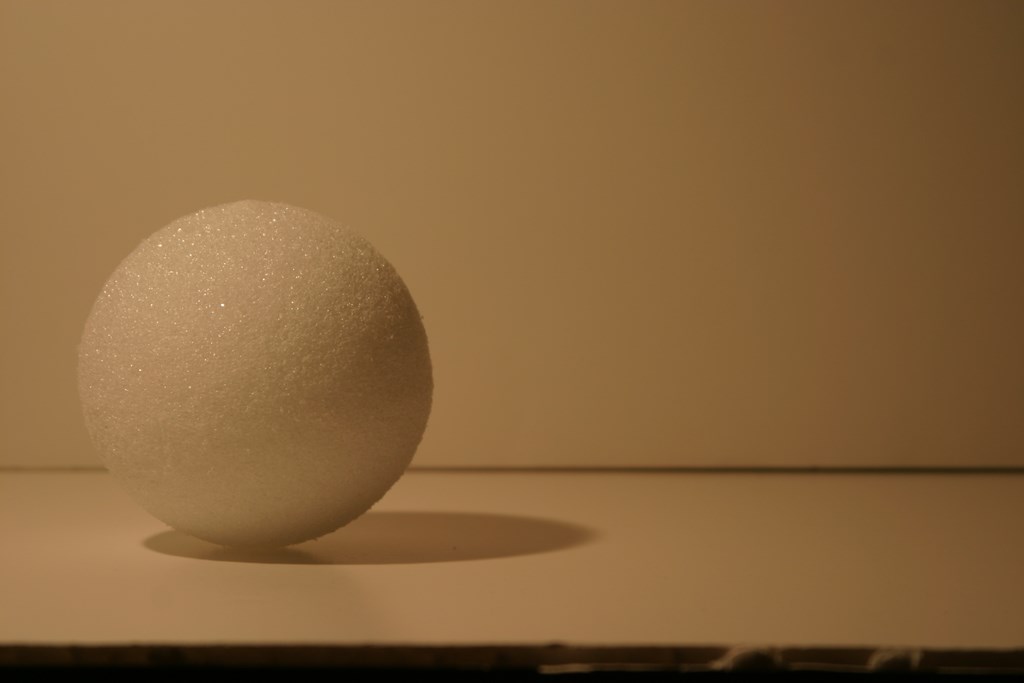

Take a ball sitting on a flat surface: When you look at it, the ball instantly seems round. The reason it does is because of the way it interacts with light. How the light hits the ball, in other words, determines the variations in color tones that our eyes will perceive in a way that gives the ball the appearance of being round and three dimensional.

ON THE BALL

Let’s keep looking at that ball for a moment: Where the color appears darker (that is, where a lesser amount of light is shining on it), the surface of the ball appears to move away from the observer, generating and reinforcing the sense that it is a round object (Figure 1). The light and the angle at which it hits the ball also determine how and where and to what extent the ball casts its shadow, a detail that further enhances our sense of its dimensionality. Finally, in the absence of light we cannot see the ball at all and therefore perceive nothing about it.

| Figure 1: As you move the light source around the ball, you can easily see how the angle at which the light strikes the ball influences the perception of its shape and volume and the degree to which it casts a shadow. |

Go ahead: Take a ball and put it on a table. Now take a flashlight and shine it on the ball, moving the light source around to various points. You’ll see clearly how the tones on the surface of the ball change as you move the light source around – how the shape of the shadow changes, what happens when you shine the light down from directly above the ball and then what happens when you change the angle off to one side or stop pointing it directly at the ball.

This small exercise is important to the development of a designer’s eye: It’s critical to understand the importance of observing objects by surveying not only the objects themselves, but also the space that surrounds them. This surrounding area is known as the negative space – a zone around an object that has its own distinct shape that is the inverse of the object to which it is adjacent.

Figure 2A shows a shrub. In Figure 2B, the negative space has been colored to highlight it. I know this concept is old hat to many of you and probably seems overly abstract to the rest, but this simple observational skill is the key to observing spaces and perceiving the shapes of the objects they include. This is literally about thinking outside the box of common observation – and one more behavior that adds to your development of design skills. Ultimately, it will help you to do your job better.

| Figure 2: The concept of ‘negative space’ is illustrated by these two views of the same tree in a landscape. On the left is the tree in its setting; to the right is the tree with the background masked – a difference a designer needs to perceive in laying out a space. |

Now take the ball exercise and move it outdoors – without the flashlight if you’re lucky enough to have a sunny day. Approach any plant in a garden and start by observing individual leaves. Notice how each leaf is different from the rest and how the light hits each unique shape, each curl, each detail of venation. Notice how each leaf’s position and angle relative to the sun or your artificial light source is what drives how you perceive it. A dark leaf, for instance, may appear white when seen in the “hot spot” where the light hits it with great intensity. Conversely, it may appear almost black when caught up in shadow or placed indirectly in relation to the light source.

Now look at a shrub – a massed collection of leaves – and notice how it interacts with the light. Take a step back and notice how the angle of the light source determines how you perceive the overall shape of the plant. In a sense, you can now think of the plant as a ball, go back to the earlier discussion of light and shadow and understand what’s happening in a garden in a whole new way.

KEEP LOOKING

With this exercise under your belt, take the program to the next level by standing back and looking at the entire garden. Do so at different times during the day and see how the changing light patterns affect how you see the garden and the overall composition. Notice in particular how colors change in different ways depending upon the intensity of the light and the time of day – and how the shadows created by the different features of the landscape add depth and dimension to the visual plane.

To continue and valuably reinforce this education, repeat the exact same exercise at intervals throughout the year: Your perception of the effects of the angle of the sun will expand exponentially, as will your capacity to perceive the role of change and your ability to anticipate what it means to the impressions taken by the less-trained eyes of your clients.

Be aware, of course, that these exercises are steps in a process and that training your eyes to see things in this deliberate way won’t lead you immediately to churning out incredible, never-yet-imagined designs. Be aware as well, however, that by changing your thought patterns in these perceptual areas you will begin to incorporate your new observational skills into your everyday life and understand how it begins to train your eye as a designer.

For watershapers, these same skills can be applied to the surface of the water, the structures that contain it and its immediate surroundings. They can guide you in placing watershapes in landscapes by helping you see shadows and light in new ways and will inform your decisions about whether to go with shadow-rich cantilevered coping instead of shadow-defeating perimeter-overflow approaches. It really doesn’t matter what type of design we’re talking about: These skills translate to just about everything we do or can do.

One way I’ve found to hone my observational skills is to take walks. For a period of about ten years, I walked the same eight-mile route two to three times a week. Beyond the obvious physical benefits, I was actually doing plant and design research.

This exercise of walking by the exact same gardens over and over again while constantly looking at details and perceiving these spaces’ evolutions has enabled me to make educated recommendations to clients about the long-term performance of specific plants, hardscape details and design elements. Also, I was much more able to serve clients in the general area around my route, leading them to places where they might see certain plants and impressing them with the fact that I sounded intelligent about details most people simply overlook.

The idea is to begin focusing your eye to observe things that you’d normally take for granted. Clients all want to know that you’re a good designer, but more than that, they want to see it in practice and feel confident during the design process that they’ve made the right choice. It boosts your credibility to demonstrate your observational skills in the way you describe design elements and how they will harmonize and balance better in the landscape; it also helps to be able to show directly how these ideas have been put to work in a nearby setting.

Ultimately, it’s part of being a designer rather than just saying or thinking you’re one.

Next: Taking the next step and evaluating how contrasts in colors and design elements will affect a landscape.

Stephanie Rose wrote her Natural Companions column for WaterShapes for eight years and also served as editor of LandShapes magazine. She may be reached at sroseld@gmail.com