The Art of Finishing

The art of watershaping so often is all about the art of finishing. Certainly, every stage of any project is important, but the final steps leading to completion are what make most designs come to life.

The project pictured here, which I’ve covered in five of my “Details” columns during the past couple years, has been an undertaking of extraordinary scale and mammoth complexity. As I mentioned frequently in those columns (November 2003, January and February 2004 and January and February 2005), the lion’s share of the project management fell to my east coast partner and dear friend Kevin Fleming, who truly has endured a baptism of Tisherman-style fire as he

has marched his way through each successive step.

Time and again, Fleming and I have been reminded, painfully at times, that residential projects of this magnitude are unusual in rural south-central Pennsylvania, where most jobs involve off-the-shelf vinyl-liner pools or cookie-cutter concrete pools. Yes, custom watershapes have been built in the area, but it soon became apparent that the trades and sub-trades simply weren’t accustomed to working at this level.

With persistence and patience, however, the job is now nearly complete with the exception of the landscaping and application of a handful of aesthetic touches that will come with better weather in the Spring of 2006.

When the grounds have been planted and dialed in visually, we’ll finish up this long suite of articles with a pictorial on the finished product. In the meantime, let’s take a look at the final stages of a job that stands as one the most satisfying I’ve ever tackled.

LONG ROADS

Let’s reset the scene:

We knew going in that this project near York, Pa., would offer challenges with respect to both project management and execution. My partnership with Kevin Fleming in our company, Liquid Design of Cherry Hill, N.J., was relatively new when our work started, and in the early stages I traveled to the site every week or two.

For his part, Fleming was there constantly, grappling with the isolated conditions, innumerable supply problems and a shortage (with a few key exceptions) of skilled labor while he himself was learning about the importance of paying close attention to every detail from start to finish.

| The awesome view from the deck overlooking the pool, spa and waterfall also reveals the beach entry, the band shell (which is to be finished in a color that helps it blend more easily into the background) and the gazebo. But I enjoy moving down for a deck-level view, which gives a clearer sense of how this grand but neatly encompassed entertainment space works and will be used once our work is done. |

As it unfolded, the process proved to be arduous even when it came to things that should have been simple. Perhaps the biggest challenge we faced was the difficulty of finding local subcontractors skilled enough to do what was needed, which meant bringing in lots of people we knew from our projects in New Jersey and California.

This left us (mostly Fleming) to pay extremely close attention to each and every step and to manage things when corrections were required, as they often were in the early going. The deck drains, for example, are based on one of my favorite details in which we’d leave out the grout around a stone that would serve as a removable drain head. It’s a straightforward process, but we couldn’t find anyone who’d ever done anything like it before. This meant that I had to teach Kevin how to execute the detail so that he in turn could teach and supervise the sub-contractors.

We ran into the same sort of challenge when it came to setting the ledger stone and communicating exactly the way we wanted it to interface with the other materials. Before long, our guiding principle of super-close supervision applied to such commonplace issues making certain that decks were pitched toward the drains and that good installation practices were being applied in setting the equipment, building the forms and pressurizing the vast network of plumbing.

| The most finely detailed part of the project is the waterfall structure that flows from the upper level and down under the bridge into the plaza. The composition took shape in a number of stages once the pool and spa island were well under way, rising between massive bridge supports to become a multi-tiered, boulder-strewn, heavily planted and, ultimately, completely natural accent within a distinctly architectural setting. |

The glass tile finish in the spa was a particular challenge, and this isn’t necessarily a regional thing: Truly competent tile setters are simply very hard to find. After a long local search, we came up empty in our hunt for someone to install the small glass tiles in the spa and inside the band shell adjacent to the pool. At significant expense, I flew in my west coast tile installer, Willie Vallenueva of J.W. Designs in Los Angeles.

My long-time friend – one of the finest craftsmen I’ve ever worked with and an incredibly talented artist who understands what makes the difference between beauty and a visual disaster – Vallenueva knows all there is to know about various mounting techniques, floating the surface and working on radii and other tricky contours.

The tile we used is from Sicis of Ravenna, Italy – an iridescent silver glass in a custom, jog-jointed pattern. It looks amazing with the creams and grays of the Sweetwater stone with which we surrounded it. We also used flush-mounted eyeballs (impossible to find locally because apparently nobody ever uses them, so we shipped them in from California).

SUPER-SIZED

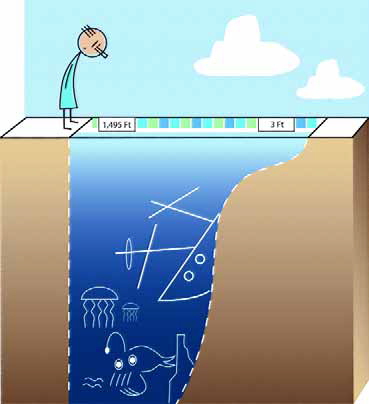

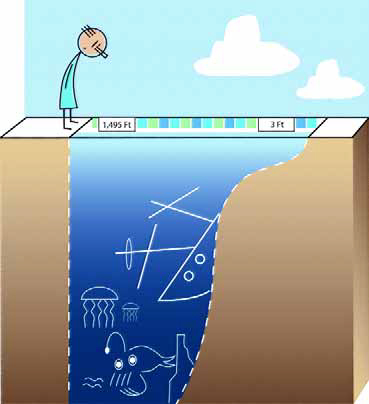

Beyond the basic management issues, we were challenged by the sheer scale of the project. The pool alone is enormous, at approximately 1,900 square feet, and then there’s the stone-finished concrete bridge; the island spa; a 20-by-18-foot waterfall feature finished in a variety of ledger stone, boulders and plantings; a tile-lined band shell; and a huge gazebo.

The entire design was conceived to stand out in a grand space, to make bold statements in a hugely opulent setting. This is a case, in other words, where subtlety was definitely not a goal: In this setting, draped in the shadow of a 40,000 square foot home, these watershapes could not be allowed to retire into the background.

| The finish work in the waterfall area was intense, as the span was to serve as a naturalistic link between a pond on the upper level and the entertainment-centered plaza below. There’s incredible detail in the rockwork, boulders and ledger detailing – and all will be softened and accented by plants that will grow in the pockets we established from top to bottom of the structure. |

Indeed, nothing about the project was understated. When we purchased stone, for example, we traveled the back roads of Arkansas to select literally hundreds of tons of material. What seemed at the time like supreme overkill was actually close to right on; indeed, only six of the hundreds of boulders we selected were not incorporated into our work on site.

The labor and attention to detail that went into the selection and placement of each boulder was enormous. We spent weeks in this painstaking work and had to maintain a constant vision of precisely what we were after at all times. We also struggled against the natural tendency in a repetitious process to cut the occasional corner. In one instance, we had a massive boulder fall out of its setting because the bottom of the boulder hadn’t been properly pressure-washed before it was moved into place. This was not an experience that recurred.

Time and again, people we worked with (and others who came on site to see the work in progress) told us that had never seen anything like what we were doing. The waterfall in particular was a source of curiosity and amazement: As it passes under a big concrete bridge, the water pauses in a variety of ponds interspersed within the structure.

| From the bridge looking away from the plaza, you can see the pond up on the house level. It seems to flow toward the waterfall structure (although the systems are completely separate) and down into the pool. This bird’s-eye view shows several of the planting pockets arrayed within the waterfall. When the greenery thrives, the whole system will seem more natural and visually accessible. |

The homeowners, workers, construction supervisors and everyone else saw us placing the multiple suction, return and bleed-off lines. They also watched as we set boulders to shape various weir details and cascades with a range of whitewater, serrated and sheet flows. There was one constant question: “Why are the pipes you’re using so much bigger than anything we’ve ever seen used on a pool or spa?”

They also were interested in the planting pockets we located throughout the waterfall structure – each with drain, lighting and irrigation lines – to soften the look of stone and the water flows. It was all very complex, with countless pipes woven in and around the big boulders, and what we were doing seemed to rivet the attention of anyone who happened by.

To be sure, you can only execute a project like this with strong manufacturer support. In this case, that level of commitment went well beyond the usual, particularly in the case of Chris MacDonald and Dave Kolstad of Pebble Technology (Scottsdale, Ariz.), who sent several technical staffers to oversee installation.

STARTING THE FINISH

When we were finally ready to fill the system with water and start it up, we ran into another odd hitch.

We called more than a dozen service companies in the area to find a start-up specialist. To their credit, they all showed up, but every single one of them took one look at the complex equipment set and its 13 pumps, four heaters and arrays of filters and control systems and told us they couldn’t or wouldn’t do the job.

| Returning to the plaza level and moving toward the waterfall, you pass by the gazebo, expansive decks and band shell, marking a progression from the architectural and artificial to the natural and free-form within a relatively compact space. |

One deeply confused technician told us he wouldn’t work on any pool that used saltwater chlorine generation, advocating instead the use of trichlor tablets in a floater or the skimmer. When he saw that we’d also used an ozone system, he was absolutely bewildered. If this hadn’t been a typical response, the individual episodes in the drama might have been amusing.

Finally, we found a company – Aqua Specialists of Mechanicsburg, Pa. – that was willing to take on the start-up. In fact, company owner John Sieck and service manager Ray Knepper, seemed to enjoy the challenge.

|

Regional Blues In the years since I started working extensively on the east coast, I’ve been disappointed by (and critical of) the mainstream watershaping industry there. Although I’ve run into wonderful exceptions, the basic mentality is that off the shelf is best (local outlets, for example, are still pushing the use of flex pipe for inground spas, a practice that hasn’t been recommended for 20 years!) and that quality in materials and detailing is an unnecessary and even questionable goal. I’d love it if this weren’t so pervasively the case. On the project described in the accompanying text, my partner and I burned countless hours teaching, reteaching, doing and redoing details and processes to develop a cadre of talented electricians, plumbers and masons who finally recognized what we were after and were willing to consider the possibility of doing things in new and different ways. As we move into other projects in the region, I’m hopeful that this process of learning and development will continue and that a more refined approach to the work will develop and become available to other designers and builders who need support at this level. The project seen in these pages is testimony to the fact that work at this level can be done: Perpetuating these approaches and transferring them to our projects and the work of others then becomes the overriding goal – the high tide that raises all boats. I’ve always said that, in the watershaping industry as in life, you look for the mistakes and the successes soon follow. You don’t pat yourself on the back; instead, you look for everything you can find that needs improvement, no matter how small and subtle or large and apparent. When you do finally solve all the problems, you’ll create gorgeous work. On this project, finding those solutions took a while, but everything came together at last. — D.T. |

Before we activated the system, we were understandably curious about how everything was going to work. We had a good idea that it would all go smoothly, of course, because we’d taken every conceivable precaution and done all we could to ensure a positive result, but the fact remains that whenever you start up a system with so complex a set of components and watershape elements, there will likely be a glitch or two.

In this case, we had a single frozen pump. We called Steve Markowitz at Jandy Pool Products (Petaluma, Calif.), explained the situation to his assistant in Steve’s absence and received a new pump two days later – just the attentive level of service we’ve come to expect from them. Once the replacement was installed, the system worked beautifully. And just as we hoped, the multi-level, multi-flow waterfall effects proved to be wonderfully exciting and complex.

At the time we fired up the system, there were some 70 or 80 people on site working to finish the home. When the water started flowing, everyone dropped what he or she was doing to watch the enormous watershape come to life. Many of them said they’d never seen anything like it in a residence before.

Best of all, in the weeks following the start up, we haven’t heard a peep from anyone: It’s all been working perfectly.

David Tisherman is the principal in two design/construction firms: David Tisherman’s Visuals of Manhattan Beach, Calif., and Liquid Design of Cherry Hill, N.J. He can be reached at tisherman@verizon.net. He is also an instructor for Artistic Resources & Training (ART); for information on ART’s classes, visit www.theartofwater.com.