At Play in the Fountain of Life

From the start, this project was meant to be something truly special – a monument symbolizing the ambition of an entire community as well as a fun gathering place for citizens of Cathedral City, Calif., a growing community located in the desert near Palm Springs.

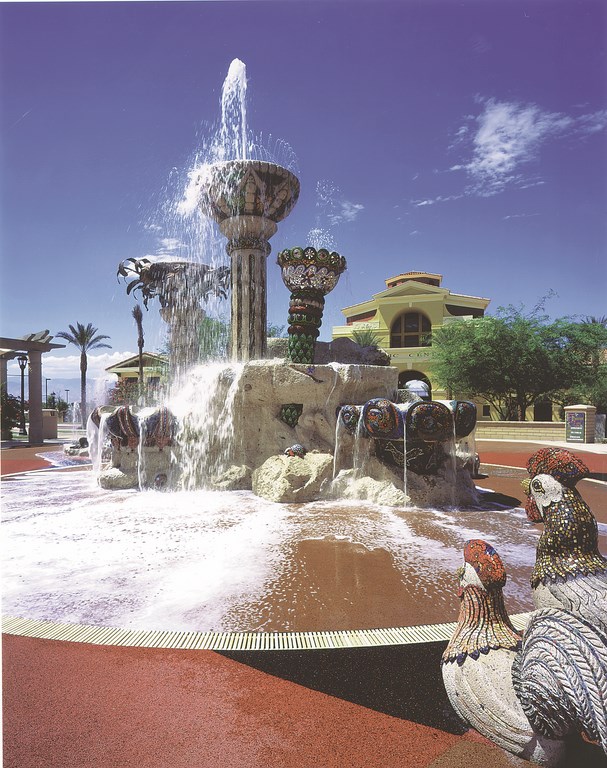

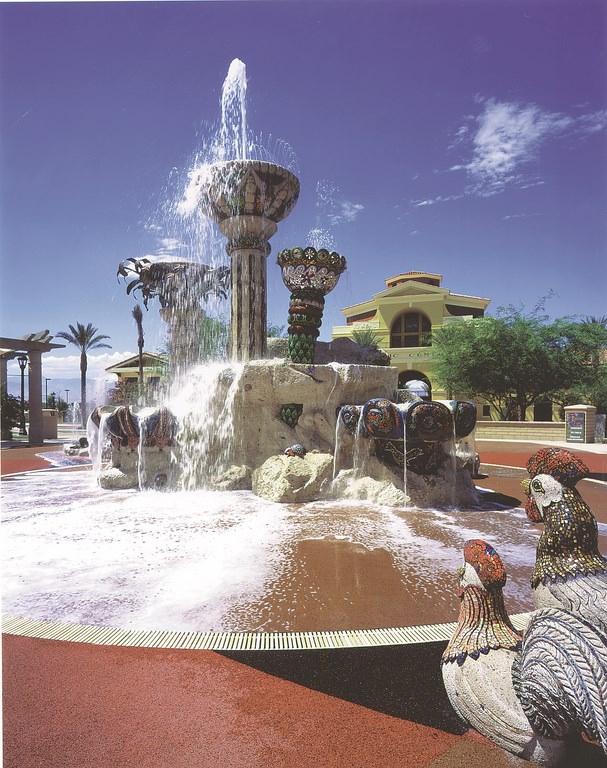

“The Fountain of Life,” as the project is titled, features a central structure of three highly decorated stone bowls set atop columns rising into the desert sky. Water tumbles, sprays and cascades from these bowls and other jets on the center structure, spilling onto a soft surface surrounding the fountain. All around this vertical structure are sculpted animal figures – a whimsical counterbalance that lends a light touch to the composition and opens the whole setting to children at play.

I’ve been building stone fountains for 18 years, and I’ve never come across anything even close to this project with respect to either size or sheer creativity. Making it all happen took an unusually high degree of collaboration on the part of the city, the artist, the architects and a variety of

contractors.

SETTING UP THE TEAM

Our firm, Casa de Cantera of Oxnard, Calif., was hired to provide the carved stone elements. That seemed a large-enough assignment, but we soon became involved in the installation as well in coordination with the general contractor (who also happens to be my brother), Glen Dobbs of Fountain & Landscape Enhancements of Bakersfield, Calif.

The project was the brainchild of Jennifer Johnson, a designer with the Palm Springs firm Cock-a-Doodle-Doo. Johnson and the city worked with the architect, Roe Young & Associates, also of Palm Springs. By the time we became involved in 1998, the design team already had developed detailed drawings and mock-ups.

Everyone involved knew that turning this grand-scale design into reality would require a tremendous investment of time and effort in coordination and negotiation of all the details. In all, there was a stretch of about eight months from the time the team was assembled until we were actually given the contract and the green light to proceed.

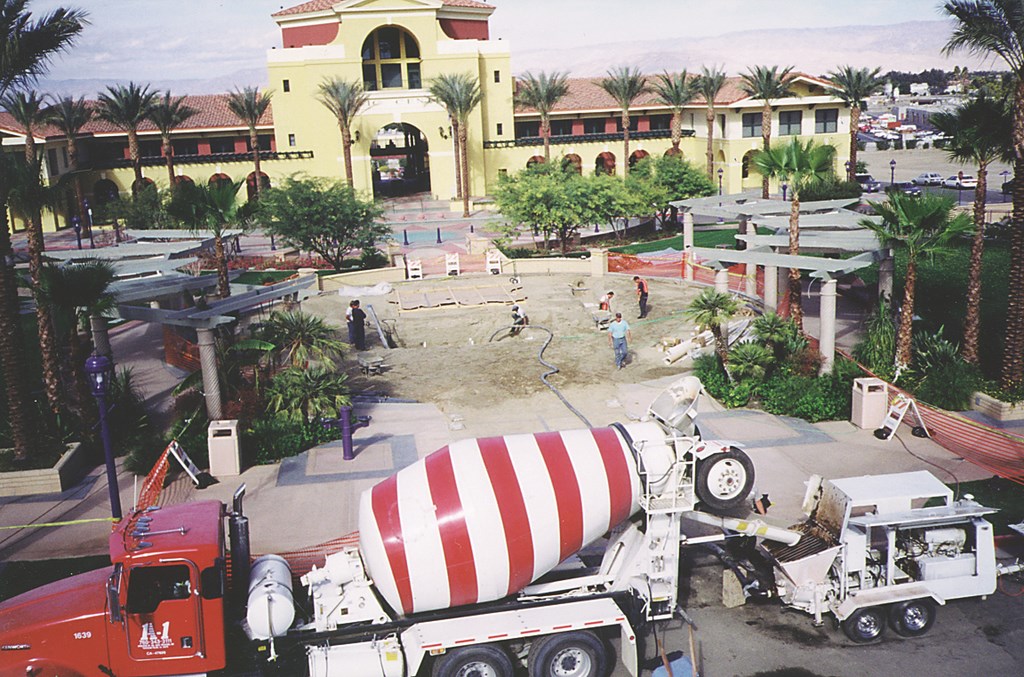

| SETTING A BASE: When we arrived on site (left), our first task (among many) involved setting up the substructure to support the massive watershape. We used a template to get the positions of plumbing and supporting columns to within tolerances (middle left and middle right) for the sub-base. Once that sub-base in and ready, we set up the metal columns that would support the fountain’s towers (right) and then poured another layer on concrete to complete the main pad. Setting one of the columns up at a slight (but structurally dramatic) angle was quite a challenge for crane and crew. |

As its name implies, the basic idea is that the fountain represents the interconnectedness of life in nature. The central structure includes three main bowl fountains at different heights, each level with various jets and cascades, and portions were to be decorated in colorful mosaic tile and other materials. Other parts were to be left bare, allowing the pale, beige stone to contrast with the brilliantly colored decorations.

Surrounding this structure are various animals – ram, turtle, fish, iguana, rooster and rabbit – all partially decorated in tile and many including water jets. The idea is that all of the animals are drawn to the central stone structure, which represents the earth or the water-giving center of life.

In down-to-earth terms, however, what the various figures and waterfeatures really offer is a clarion call inviting children of all ages to play and get wet.

TAKING SHAPES

All of the stonework – the central structure as well as the animal sculptures – is carved of granite mined in the vicinity of our factory near Guadalajara, Mexico. The specific granite we used is known as a light pinion – not rare, but not commonly quarried and carved.

After we received the order for the stone elements, we carefully sized up the pieces we’d need and went into the mountains to find the raw material. In all, the quarrying crew from our factory spent three weeks in the mountains, extracting pieces we thought could be carved into the various fountain elements. The center element alone, we estimated, would take 59 custom-carved pieces.

Believe me, removing pieces of this size is extremely labor-intensive and is achieved mostly with hand tools, leverage and gravity. In all, we carted approximately a hundred pieces of various sizes back to our shop.

| LAYER UPON LAYER: Once the foundation was set, we took full advantage of the fact that the fountain had been completely assembled in Mexico and had been clearly marked to simplify reassembly on site (left). It went up like a layer cake, one level at a time, and came back together according to plan (middle). At the same time we were active in building up the central structure, we were also working on the perimeter drain system and in preparing the area around the central structure to receive a spongy decking material (right). |

We started our work using the designer’s scale model and the architects’ drawings, and the carving alone took more than five months to complete. Our very best sculptors, all local craftspeople, focused almost exclusively on this project for the duration, and even I was amazed at their efficiency as the various elements gradually took shape.

All through this process, we were in constant communication with Johnson, the architects at Roe Young & Associates and representatives of the city. Johnson was particularly helpful, making suggestions that helped us understand her vision and keeping us on track. Of particular importance was the information she gave us on where to provide “relief” in the stone surfaces where she intended to place mosaic details: We all wanted the end products to be as smooth as could be.

Eventually, we were able to pre-assemble everything at the factory, making certain of the fits of connected components and also making doubly certain that the actual work reflected the model and plans. Once we made the final adjustments, we labeled all the pieces with care, packed them in crates and set up a truck convoy to cross hundreds of miles of Mexican highway.

ON LOCATION

By the time we arrived, a holding yard had been set up near the installation site, giving us enough room to unload and organize the pieces of stone. Nearby, a tent was set up in which Johnson and her tiling crew began applying the mosaics to the stone.

While this big job was under way, we pre-assembled the center element over a grid of railroad ties. This enabled us to slide sheets of plywood beneath the stone pieces and create an accurate template of the structure’s footprint. In turn, this template would enable us to fix the position of the element on the construction pad – a critical need in locating the plumbing runs and the conduits for lighting.

As assembled, the center element weighs in at nearly 100 tons, which called for a significant foundation. Structural engineer Paul Singer, also from Oxnard, specified a 12-by-14-foot pad, 4 feet thick. Given its sheer mass, we knew we there’d be no chance to go back: Everything had to be perfectly positioned beneath the fountain structure.

| MARKS OF DISTINCTION: As we were working away at the structural elements of the watershape, a crew of tile artisans worked on decorating various components with elaborate, colorful tile mosaics (left). One these components were ready (mostly anlimal forms, but also some key parts of the central structure), we moved them to their final spots in the fountain assembly or on the surrounding deck (right) |

Working with great care and always observing the old carpenter’s rule, “measure twice, cut once,” we established a center point in the template and cut holes in the plywood sheets to determine the exact locations of standpipes that would carry the plumbing and electrical conduits.

The pad was then set down in two pours, the first being the most critical in terms of placement of the conduits, which were routed through large iron standpipes ranging in diameter from 6 to 14 inches. Once the lower pad was set and we’d double-checked the standpipe positions, we poured the second tier to complete the base.

I’m making this seem like a linear process, but the truth is that a whole lot was going on simultaneously. As we built the pad, we were also digging out the equipment vault and assembling the structure while the tile was being applied to individual components. In addition, we were doing preliminary work on the pads and plumbing for the animal sculptures and preparing the deck for application of the soft surface material.

Around this whole area, we also set up for drainage via an encircling gutter system with a diameter of 60 feet. In effect, water from the fountains flows freely over and through the permeable, non-skid rubbery surface and is directed outward into the perimeter’s sub-grade gutter.

A LAYERED APPROACH

At last, it was time to install the stonework.

The center fountain structure was built as three levels. The first row was laid on the pad around the standpipes in a location precisely established by the template. Next, slots were cut into the bottom of the base stones. Here we tied in loops of rebar, cemented into place using a special epoxy/mortar mixture. Now holes were cut in the tops and sides of the stones for more rebar that would be used to tie everything together and provide stubs for the loops we would use to “stitch” this level together with the one above.

In the first two levels, we’d left a large void in the center of the stones. Once all the pieces were positioned and tied together, we filled the void with poured concrete, flush to the top. The second tier was placed in much the same fashion, all tied together with rebar and the special mortar and then filled before we moved on to the third level that crowned the structure. There’s also a fourth structural section at the back of the second level from which a series of interactive spray jets emerge and drench passersby.

Once it was all put together, the central structure was really one solid piece. At that point, we began adding the columns for the bowls, lowering each over its standpipe. (Note that one of the columns is tilted, an effect that took some careful structural planning – and tricky maneuvering with the crane.)

Much of the tile had already been added as we assembled the center element – and now we all began to see just how striking the whole composition would be. We all watched with growing pride and excitement as finishing touches were added, including the hammered-brass palm leaves on the shortest column.

| EMERGING FORMS: As all of the various components we’d worked on through a period of months began to come together in final form (left) – complete with the tile decorations that we’d so painstakingly made allowance for in our shop in Mexico – we witnessed the arrival of a monument to the power of water to shape arid spaces (right) and found satisfaction that comes only in working at the highest levels of creativity, collaboration and attention to detail. |

The positioning of the animals around the fountain was not as critical, but by this time we weren’t leaving anything to chance. We made templates of the bottoms of each animal and used those to establish the exact locations in a meeting with the city, the architects and the designer. Once we’d staked down those locations, we finished the plumbing runs and set up the animals’ supporting foundations.

That done, it was time to install the surface material, which is made of a combination of reprocessed automobile tires and epoxy resins. The surface is four inches thick at the center, sloping very gently to three inches on the perimeter. Water flows outward over and through the spongy material, eventually finding its way to the encircling gutter.

In the vault, we set up two 10-horsepower pumps that drive all the waterfeatures. The control panels and plumbing configurations were handled by Fountain Supply Co. of Valencia, Calif. In all, there are 35 different water elements with a variety of nozzles and spray effects in a system that holds approximately 10,000 gallons of water drawn from a sub-grade surge tank. Given the desert climate and large surface area, we set up an auto-fill system to compensate for rapid evaporation.

LOCAL FLAVOR

Unlike other portions of California that depend on aqueducts for their water supplies, all of the Coachella Valley’s water is drawn from local wells that tap a massive underground aquifer.

Despite the growth in the area, local geologists assure city leaders that water in the aquifer will continue to be available in great abundance, constantly fed by the watershed in local mountain ranges. As a result, the communities in this area are famous for their swimming pools, water-hungry golf courses and fog-misters that cool sidewalk cafes and outdoor pedestrian areas – and this fountain fits right in.

Dedication ceremonies were held in July 2000, a gala affair widely covered by local media. It was great to receive praise and recognition from the city’s leaders, but the greatest satisfaction has and will always come from watching kids frolic and play. As intended, the fountain has become a symbol for the community as well as a popular gathering and play area.

For all of us who participated in this magnificent project, it will always be a point of pride.

Eric Dobbs is founder and president of Casa de Cantera, a supplier and installer of custom carved stone products based in Oxnard, Calif. Dobbs has been in business for more than 19 years, providing beautiful custom stone products to contractors and designers working on a broad range of commercial and residential projects, including elaborate fountains that feature large sculptural figures as well as bowls and basins. The company operates a manufacturing facility near Guadalajara, Mexico, near where the stone is mined.