A Master at Work

I first became an admirer of Roberto Burle Marx while I was a student in landscape architecture at the University of Florida: His remarkable work, which combined a special brand of modernism with the lush potential of Brazilian settings, was incredibly powerful and the major formative influence on my own professional career.

I’d learned how to draw in school and had acquired the technical skills it took to be a landscape architect, but it was seeing how Burle Marx approached his landscapes and paintings – not to mention the way he lived his life – that gave me the spark I needed to define my own approach.

My personal relationship with him began soon after I graduated in 1981. I’d read an article in the Miami Herald about Burle Marx turning 70 and began writing to him in hopes he’d invite me to visit his home in Brazil. A couple of months later, I received a call from my friend Lester Pancoast, a well-known Miami architect. Burle Marx was in town and was staying as his houseguest, Pancoast explained, suggesting that since Burle Marx had a free evening I might want to take him to dinner.

My future wife and I spent a nice evening with Burle Marx, who was reserved but very polite and seemed all the while to be sizing us up. After dinner, we went to Pancoast’s home, where Burle Marx showed us

some amazing black-and-white etchings he’d recently completed and offered to sell them to us for $500 apiece. We immediately latched onto a couple, and it was obvious that he appreciated people who appreciated his art.

It was the beginning of a friendship that would last the 14 years until Burle Marx died in 1994.

GOING SOUTH

About two months after our first meeting, Burle Marx was passing through Miami on his way home and had apparently paid some attention to my requests to see his work in Brazil at first hand: I jumped at the chance when he asked me to join him on his return trip. When we arrived in Rio de Janeiro, I humbly asked when I might visit his home. Now, he told me, ushering me to his vehicle to join several other people in his entourage.

It was fascinating to watch the way he lived his life. He approached everything he did with the same passion and boldness that defined his work and loved being surrounded by all sorts of interesting, creative people including sculptors, painters, botanists, architects, writers, musicians and others who regularly spent time with the great man. We shared good food and fine wine and generally had a wonderful time.

He was one of those people who seemed to thrive at the center of an incredibly dynamic scene. I came to see being around him as participating in an ongoing celebration of all things artistic and creative.

| No matter whether the project was commercial or residential, large scale or small, Burle Marx approached each setting individually and had an amazing ability to approach a space without relying on formulas, conventions or preconceptions. This tendency toward originality showed up with particular clarity in formal architectural settings, where he played off rigid forms by using plants and water in immensely creative and imaginative ways. |

Experiencing all this at a young age really opened my eyes as to how a person could live an artist’s life. I was impressed, for example, by the way he ran his studio: It wasn’t in any way an oppressive work environment, but was instead a free-wheeling agglomeration of constant creative energy. His associates came and went with great freedom so long as the work was done. And that work was amazing, as he seemed by strength of personality to draw the very best out of his colleagues – all of whom seemed to have the same admiration for him that I did.

I never worked with him on any project, but I did have the privilege of visiting him at least once each year to recharge my creative batteries. I was particular happy to visit in August, when he’d host these massive birthday parties attended by scores of interesting people: They were, quite simply, some of the most memorable events I’ve ever attended.

Once the festivities were over, he’d lead us on excursions to study gardens or collect plants in the wild. Through it all, he was remarkably generous; in fact, only my mother outranks him as the most giving person I’ve ever known: He was an open book, always more than happy to talk about his work or share anything by the way of prints or sketches from his office or cuttings from his nursery or garden.

It was as if life was somehow bigger or more important when we were in his presence. Burle Marx truly was larger than life, one of the kindest people I’ve ever known – and a lot of fun besides.

PERFECT INFLUENCE

As much as I admired his passion for life, I can’t even begin to describe the depth of Burle Marx’s influence on my work.

Through the years, he always passed through Miami on his way to wherever he might be going in the United States, and he was often a guest in my home as a result. During those visits, I’d always show him drawings of projects I was working on, and if time allowed we’d also visit some of the gardens I had designed.

He was always completely candid in voicing his opinions and never hesitated to tell me what he liked and didn’t like. He had colorful way of expressing himself, but there was never any doubt about what he really thought. I learned a great deal from these vivid critiques – so much so that to this day, I still think in terms of what Burle Marx would do or say in a given situation.

To this day, however, I find it difficult to describe Burle Marx’s work in words: You really have to see and process several of his projects to understand his approach to landscapes. He was incredibly perceptive, always had a keen sense of how to dissect a given space and abhorred the thought that there could be any specific formula for design success. Always, he approached each space on its own merits and terms.

| The four projects in the top row are by Burle Marx. Although he used nature for inspiration, he wasn’t particularly inclined to mimic it directly. Instead, he used plants, stone and water to suggest nature in the midst of spaces clearly laid out and intended for human use. This is a tactic I’ve often used myself, setting up spaces (as seen in the image on the second row) that are clearly non-natural but using plants and water to tie everything back to common experiences of nature. |

His work is often described as modernist, but at the same time, everything he touched was obviously and deeply influenced by natural forms. He often used groupings of the same type of plant, for example, and was a careful student of botanical forms and structures. He also believed that, as a designer, he had an obligation to stay up to date and work with the best available tools and technologies.

Most of all, he was always inventive. He might, for example, take the stones from an old building to create a texture wall, but there was never a sense that this was mere decoration. He was appalled by neoclassicism, but there was still a timeless quality to his work. He believed that color should be applied for specific reasons and never splattered them about for their own sake. If he used red, for example, it was subordinated to the overall composition and usually served the specific purpose of drawing attention to a particular part of the design.

Despite the influence of nature on his work, however, Burle Marx never directly emulated nature. If he created a waterfall, for example, he’d use the stone material to shape architectural statements that he controlled. In effect, while his work always harmonized with natural settings, it was obviously man-made. In his warm minimalism, he revealed his mastery by blurring the boundaries between natural and built environments.

POSITIVE REFLECTIONS

I’ve never sought to copy Burle Marx in my own work, but his influence is certainly evident in almost every project I’ve ever done.

As he did, I believe very much in working with a contemporary, modern vocabulary and avoid classical forms. Unlike his gardens, however, those I design are often quite natural in appearance – visually strong, but carrying the appearance of naturally occurring phenomena.

I also draw contrasts by using architectural elements in much the way he did. My hardscapes tend to be very strong and clean, and I love the minimalism found in Japanese architecture and a number of contemporary architects and designers – Burle Marx chief among them.

I don’t work with formality of the sort seen in European gardens and, like Burle Marx, try to use the geometry of modernism to emphasize the natural elements in plantings, water and stone. Sometimes those spaces are “organized” and may seem formal, but my aim, which I’ve borrowed from Burle Marx to a large extent, is to create both harmony and tension between nature and structures arrayed in its midst.

| As is seen in the first three images in the top row, Burle Marx often used architectural forms in his waterfeatures, playing with contrasts between natural and artificial statements to highlight spaces and bring them into harmony with their overall surroundings. His sense of these shapes was well ahead of its time – he was truly one of watershaping’s pioneers – and his work exemplifies design insights and details I’ve translated and played with throughout my own career, as I trust can be seen in the photographs at top right and on the second row. |

In that sense, we have a similarly playful approach to two prevailing schools of thought: On the one hand, modern architecture is seen as a contrast to nature, but on the other, it can be used to fuse natural elements together with built structures. We work in both worlds, and the balances and sensations of integration can be truly sublime. A portion of a wall has a distinct form, but it never sits alone and aloof as a separate sculptural statement.

When I have the opportunity to work in a dramatic natural setting (on the seashore or in a desert or high in the mountains), striking those balances can be fairly easy because all I really need to do is to find ways to allow the beauty of the setting to invade the built spaces. Most of the time, however, I work in places that have already been touched by development, whether on the coast, in the suburbs or in completely urban locales. No matter where I find myself, the challenge is to establish gardens that bring the comfort and beauty of nature into the setting.

This is an area in which Burle Marx’s art was supreme: Wherever he worked, his desire for balance invariably overcame the human impulse to dominate nature (or even fear it).

INTUITIVE INCLINATIONS

As designers, we spend most of our time finding solutions to challenges presented by the spaces we confront, but to a large extent the process boils down to determining what we like and don’t like. That’s why no two designers are the same and, as much as someone like me can be influenced by someone like Burle Marx, the fact is that any design is the product of an individual designer’s intuitions and experiences.

Burle Marx is no different. As is the case with most great artists, his work was intricately tied to his time and place: When he was completing his early projects in the 1930s and ’40s, he was surrounded by the explosive influence of architectural modernism as it swept across the globe and its original forms were altered and expanded in response to local cultures, individual artists and interested architects.

In Burle Marx’s case, he was working primarily in Brazil through those years and is credited for pioneering modernism in his country, which is graced with incredibly bold landscapes loaded with spectacular mountains, lush flora, striking geological formations and amazing seascapes. In such settings, a designer with Burle Marx’s outgoing, engaged personality was naturally going to do bold and exciting things.

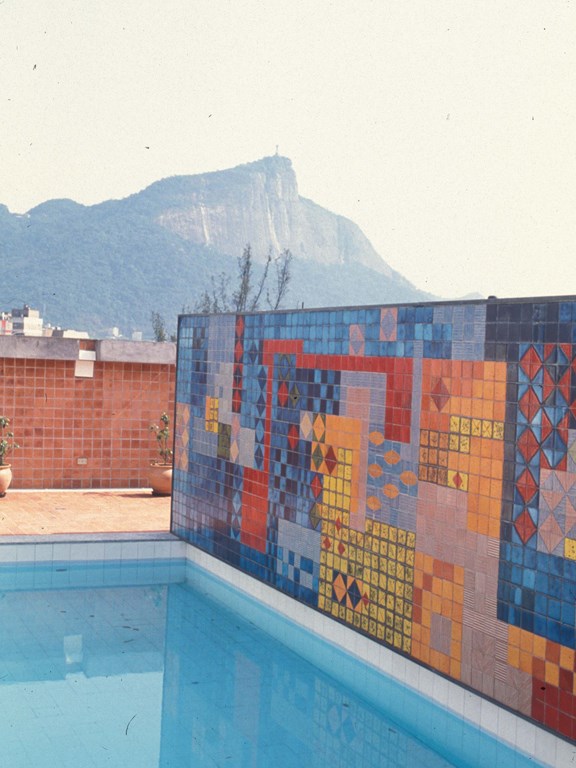

| When he explored modern styles and used more purely decorative forms, Burle Marx stepped well away from convention and emphasized the natural features of water, plants, stone and, in one memorable case, tile – even in formal or overtly geometrical settings. His work is seen in the left and middle left images on the top row. As seen in the other three photographs of my own work, I pursue the same general philosophy, which I see expressed not only in my projects but in the work of the likes of Ricardo Legorreta and Luis Barragan, with all of us striving to harmonize structures and natural forms as Burle Marx did. |

He’s renowned to this day for his use of grouped plantings, for instance. You don’t tend to see a single palm tree in the natural world, but instead of planting trees of similar size, Burle Marx would stagger their sizes to make it look as though the main trees had dropped seeds and established a colony. These plantings were a literal representation of what he saw in nature, but at the same time they brought visual structure to a space and helped observers understand the character of the plants.

Burle Marx is particularly revered for his bold patterns, but when you visit his own garden, the impression is all about softness and subtlety. I always admired him for that: These small contradictions have always kept people from packing him into any sort of conceptual box.

He was also generous in giving credit to artists whose work influenced his own. I asked him once if Japanese design had influenced him. He simply shrugged and said, “How can you go to Japan and not be influenced?”

Burle Marx also had a wonderful sense of how gardens and architecture work together. In that sense, his approach reminds me of Luis Barragan or Ricardo Legorreta, both of whom thoroughly combine their buildings with garden spaces. Their gardens aren’t particularly lush (their Mexico being quite arid compared to Burle Marx’s Brazil), but all three demonstrate a similar urge to harmonize structures and natural forms.

WATER SPIRITS

One of the things that Burle Marx had going for him was an encyclopedic knowledge of the plant kingdom and his special ability to conceptualize his way through all the possibilities in everything from lush forest settings to desert climes. (I remember asking him what he thought of Barragan; he smiled and said, “He needs to use more plants.”) No matter where he worked, Burle Marx carried that trove of information with him.

Burle Marx also shared the view with Barragan, Legorreta and others that water was a crucial design element and saw to its effective use in a large percentage of his designs.

Indeed, he used water as a fundamental building block, and I particularly admired the way he would divert parts of streams to create small pools that reflected the sky, surrounding structures and plants. He understood that water created powerful points of focus and that, as human beings, we’re all deeply affected by its presence.

In the tropics, where he did the majority of his work, water is an incredibly powerful presence both in the way it sustains flora and fauna and as a destructive force. He knew water to sooth and comfort, but he also knew it to excite and even terrify. At the same time, he knew in arid settings that the scarcity of water defines the landscape and that its presence creates oasis-like havens.

| Many of Burle Marx’s projects are overtly drawn from nature and the plants he found all around him in his native Brazil, as seen in the iamge at top left. There’s an elegance to it – as well as clear references to the great Japanese gardens he so admired – and an invitation to visitors to pause and relax. Again, this approach to natural forms fully engages my own creativity (as seen in the other four photographs) and has led me to develop spaces that pay tribute to Burle Marx and other masters who’ve gone before me. |

Burle Marx keenly understood these dynamics and used the reflective quality of water, its sounds and the structures he used to contain it to tremendous effect.

I try to do much the same in my own work, and I love to include relatively large bodies of water and use reflections to influence, for example, observers’ perceptions of interior spaces. In this way, I use water to conjure senses of grand dimensions even in small spaces that would be visually diminished without its assistance.

In a much larger sense, we’re able through water to connect just about any space to the entire universe. That may seem like overreaching, but when you see and understand the way Burle Marx and other great designers use water for just that purpose, a big, abstract idea becomes an entirely practical principle of design.

Burle Marx was ingenious as well in the ways he incorporated plants into his watergardens. Because he understood them all so completely, he was able set various species at precise elevations so their root systems took full advantage of his watershapes. In many instances, he set watergardens near swimming pools so those immersed in a fully architectural bodies of water would have a sense of connection to water in more natural forms.

THE POETRY OF SPACE

The work of Burle Marx is both powerful and effective, but it’s also so intellectually complex that it’s impossible to describe all of its nuances and the depth of his many achievements. The work is, in short, like the man himself – a personality so vivid and a knowledge so vast that capturing its essence would take volumes rather than these few pages.

|

More on Burle Marx The books on Roberto Burle Marx and his work are plentiful. My personal favorites include: Roberto Burle Marx in Caracas: Parque del Este, 1956-1961 by Anita Berrizbeitia (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005) Roberto Burle Marx: Landscapes Reflected by Rossana Vaccarino (Princeton Architectural Press, 2000) A Picture of Roberto Burle Marx by Lawrence Fleming (Editora Index, 1996) Roberto Burle Marx: The Unnatural Art of the Garden by William Howard Adams (The Museum of Modern Art/Abrams, 1991) The Gardens of Roberto Burle Marx by Sima Eliovson (Timber Press, 2003) The Tropical Gardens of Burle Marx by P.M. Bardi (Reinhold Publishing, 1964) — R.J. |

For my part, I’ll always feel his presence in my work and the way I approach my life. On the occasions when I had the opportunity to see him interact with clients – even when he was speaking Portuguese and I couldn’t understand everything he was saying – I could always tell how he affected people and perceive the respect they had for him.

There was always a feeling that something very special and important was happening, and he translated those sensations into the work at hand, weaving any space and the elements within it to create works of art that have stood the test of time. These spaces will become increasingly important as time goes by and more and more people become aware of and feel his influence.

There will never be another like him, but he certainly has influenced me and touched a great many other people through his work and in the way he approached his life. It’s all worth study by anyone who strives to create something special in designing and organizing spaces: Roberto Burle Marx may no longer be here in the flesh, but his spirit lives on!

Raymond Jungles is founder and principal for Jungles Landscape Architect in Miami, Fla. His prime inspiration and the key to his passion for landscape architecture stems from his longtime relationship with Brazilian artist and environmental designer Roberto Burle Marx, and his current practice is firmly rooted in Florida and the Caribbean basin with a focus on residential, resort and community design. Jungles’ work also illustrates his interest in and dedication to the preservation of natural habitats and the use of indigenous species. He is the recipient of more than 20 design awards from the American Society of Landscape Architects, including the prestigious Frederic B. Stresau Award of Excellence. He also was named Most Distinguished Alumni in 2000 by the University of Florida and in 2003 was honored as the Landscape Architect of the Year by the American Institute of Architects. He was elected a Fellow of the American Society of Landscape Architects in 2006.