Graphic Appeal

It comes as no shock that we remember things that surprise and fascinate us. Back in my days as a graduate student in fine arts, I was determined to exploit that very human tendency in creating nature-inspired artworks meant to evoke deep-seated memories and a personalized sense of déjà vu.

My first work along those lines involved creating a rail of ice with a central channel that carried heated air: The idea was to create a situation that reminded people of hot/cold experiences, such as the heat of a campfire on a cold night or the warmth of the sun atop a snow-capped mountain.

That project started me down a long path that eventually led me to create waterfall systems that use large quantities of precisely controlled droplets of water to “paint” kinetic graphics, logos and text – a concept I’ve continued to perfect through the past 30 years.

So far, these systems have mostly been used to display commercial messages at trade shows. It all makes sense: As deployed by exhibitors looking to amaze attendees (and by a handful of other high-profile commercial and public clients as well), the effect is meant to dominate a setting and attract maximum attention. To date, I’ve designed, programmed and installed more than 100 of these exhibits worldwide.

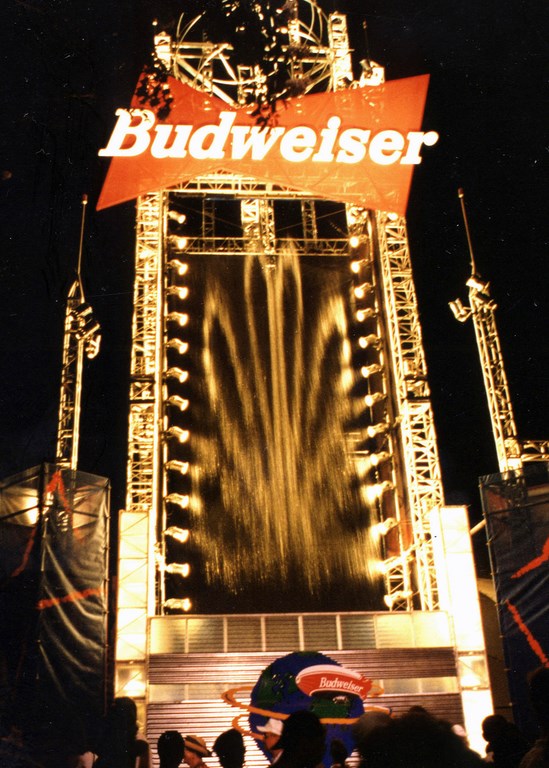

We’ve done some special events as well, including an installation seen by 24 million people who visited Atlanta’s Centennial Park during the 1996 Olympics and, ten years later, another display celebrating the 60th anniversary of the coronation of the King of Thailand – a Graphical Waterfall (as I call them) seen by five million people in the first ten days of the event.

PAINTING IN WATER

Even with all that exposure, these systems are still enigmatic – mostly, perhaps, because of the low profile kept by Pevnick Designs, my Milwaukee-based firm. Rather than promote what we do directly, we generally work through trade-show exhibit companies that are typically reluctant to tell anyone where or how they found us. Still, our level of activity has kept research-and-development money flowing and drawn enough attention to our Graphical Waterfalls to keep everything going.

From the start, these systems have always been about combining art and technology to create something unusual and visually arresting.

The basic idea emerged from a series of incremental creative steps that actually began with the ice/hot-air project mentioned above. Upon completing my Masters of Fine Arts degree at Washington University in St. Louis, I began teaching in 1973 at the University of South Florida in Tampa. Soon after arriving, I heard that the chairperson of the music department had obtained an early mini-computer (the kind run by a paper-tape operating system) that had been designed for composing and performing electronic music.

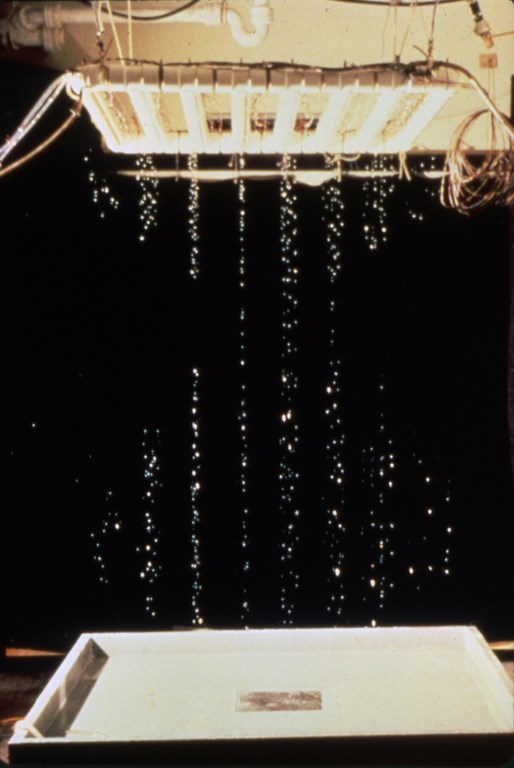

| The technology had a modest beginning with this 64-nozzle system, which produced my first three-dimensional, computer-controlled waterfall images. Completed in 1977, it depicted a diamond moving vertically through space. |

This caught my attention because, in one of my other student projects, I’d worked out a system in which droplets of water fell on five heated cubes. It was an interesting project (if I do say so myself), but I was never satisfied with it because I lacked a good way to control the droplets and create something other than a random pattern. (As I’ll discuss later on, even at this early point it occurred to me that it might be possible to create recognizable visual patterns in the streams of droplets.)

I asked the music professor if I might use the computer for the purpose of controlling falling water. He wasn’t big on the idea, but he said that if I used it for a musical purpose or at least to create a sound effect, he’d let me give it a try. I followed up with an idea inspired by the sound of falling rain – a project in which I would define a space by using the rhythm and percussion of water droplets falling on plants to create a sonic illusion of rotation in space. He loved the idea and let me schedule some computer time.

In 1974, I received a grant from the university that enabled me to take off a semester to develop the concept. In trying to create the sound effect I wanted, however, I ended up coding an algorithm that was too fast and produced a diagonal line of water droplets. My original idea of creating a water display now came back to me, and from that moment on I knew I could produce complete images in falling water.

At that point I changed directions and, with the help of a graduate student in the music department, developed the first software for the system. I then enlisted the help of a mechanical-engineering professor to design what would be the first three-dimensional, computer-controlled waterfall. Next, with help from a technician in the music department, I tackled development of the electrical interface between the computer and the valves. That first system ultimately featured a horizontal, four-foot-square array of 64 nozzles.

LEARNING TO SPELL

I continued working with this original system for about three years and, by 1977, had produced a vertical sine wave, a spiral and, finally, three-dimensional diamonds falling in space. I used a strobe light (also connected to the computer) to take photos of the early water graphics and discovered that I could animate the water-droplet-defined shapes and make them hover in space. I could also take a helix and make it hover – and then rotate the spiral clockwise or counterclockwise by adjusting the speed of the strobe.

After moving to the University of Wisconsin in Milwaukee (where I teach to this day), I installed one of the strobe-lit waterfalls at the Milwaukee Art Museum as part of a Wisconsin Directions show for Wisconsin sculptors, placing the waterfall in an inflatable black polyethylene structure so I could control the light.

After that show, I decided that I wanted to pursue the tradition of Western fountains and not use strobe lights: Their brilliance seemed to take the waterfalls into the realm of performance art, and I wanted to avoid the sense people might have that I’d shown them all I could. At that point, in fact, I was just getting started: I wanted my Graphical Waterfalls to be suitable for urban public venues as permanent installations.

| In the following years, I continued my research in valve design, always aimed at producing denser, more visible water droplets. By 1983, I had developed my first 576-nozzle module, which was capable of producing helical structures that appeared to turn as they fell. |

Soon I was given a Project Design Fellowship by the National Endowment for the Arts and used it to develop a square, 576-nozzle system that operated off a single modular valve. By 1982, I was on my way, finally able to spell out words.

A second round of funding from the National Endowment enabled me to expand the concept to a 2,304-nozzle waterfall. First put on display through the Klein Gallery of Chicago at the International Art Exhibition on Navy Pier in 1988, that waterfall was able to say “hello” in different languages and create series of helixes and other graphical images.

This trail-blazing display led to our securing a private grant from the Kohler Company that I used to develop a 12-foot-wide, 6,912-nozzle waterfall made up of a dozen of my one-foot-square units.

Kohler gave the grant to the University in exchange for my agreeing to exhibit my wares at two of their national trade shows each year. Once that relationship started, exhibit companies came calling and our waterfalls began appearing at trade shows both to display marketing messages as well as to draw attention to booths.

FOCUSED ATTENTION

I hadn’t ever considered trade shows as being the defining outlet or venue for these effects, but it proved a ready (and steady) market. As it turned out, the companies had no hesitation about funding the transport, set-up and dismantling of the systems while covering my other expenses.

To me, this was far more feasible than the prospect of participating in art exhibitions and hoping someone would notice. In addition, it soon occurred to me that some of the trade shows in which I was participating put my ideas on display in front of upwards of 100,000 people.

From the start and wherever we’ve installed these waterfalls, the response has always been strong. I often describe what happens as being similar to people sitting around a campfire: Once they lock the fire in view, they tend to spend a surprising amount of time just staring at it. Indeed, even when people are having active, animated conversations in front of my waterfalls, they don’t look at each other for fear of missing something – the next image, the next change.

It’s also like the proverbial hole in the fence at a construction site: Once one person has stopped to take a look, others tend to gather. I’ll often see the same person come back after witnessing the waterfall for the first time – but now with others in tow so they can have a look, too.

| As my experience with the technology grew, I was able to produce increasingly complex imagery – rain effects, letters moving sideways, random ribbon patterns and much more – all in my attempt to capture nature at very rare and beautiful moments. |

There’s no question these Graphical Waterfalls do as they’re intended: They draw attention and are appreciated because they do so much to increase booth traffic.

While most of the displays I’ve done will focus on commercial messages, I always insert what I call “kinetic graphics” (including various dancing ribbons, diagonal lines and waves) to hold the attention of passersby and create a “show” in which the company logo or message plays the major part.

As an artist and designer, I appreciate the value of mystery, so rarely do we give away the commercial message right at first. The more varied and complex the accompanying graphics, the longer people will spend looking at the display and absorbing its message – a fact that convinces booth sponsors to give me lots of creative leeway in programming their displays.

In these displays, my kinetic graphics are the art: They demonstrate the timing and grace that programmed falling water can have and form a link to traditional fountains. If one were to let marketing people run the show, I suspect the content would be like one continuous advertisement. My thought is that this would just make people feel as though they’re being exploited, so the way I do it, the kinetic graphics are the show and the marketing words and logos indicate the sponsorship that make the artistry possible.

A LOOK INSIDE

The element that attracts viewers to these displays is how “clean” the images are – a clarity that is the accomplishment of our exceptional computer programmer, Richard Bartlein, who has been with the company nearly from the start.

As letters and images fall from the nozzles into the catch basin, viewers perceive very little by way of degradation – and we’ve been able to achieve that degree of coherence with waterfalls as tall as 50 feet. In fact, taller is actually better with these systems, because height makes the water appear to fall more slowly – almost to the point where the droplets seem to be momentarily suspended in air.

Another point that surprises people is the optical depth these waterfalls have: We currently make systems with three, six, 12 or 24 rows of jets spanning the width of the waterfall, which gives us an ability to create amazing sensations of dimensionality.

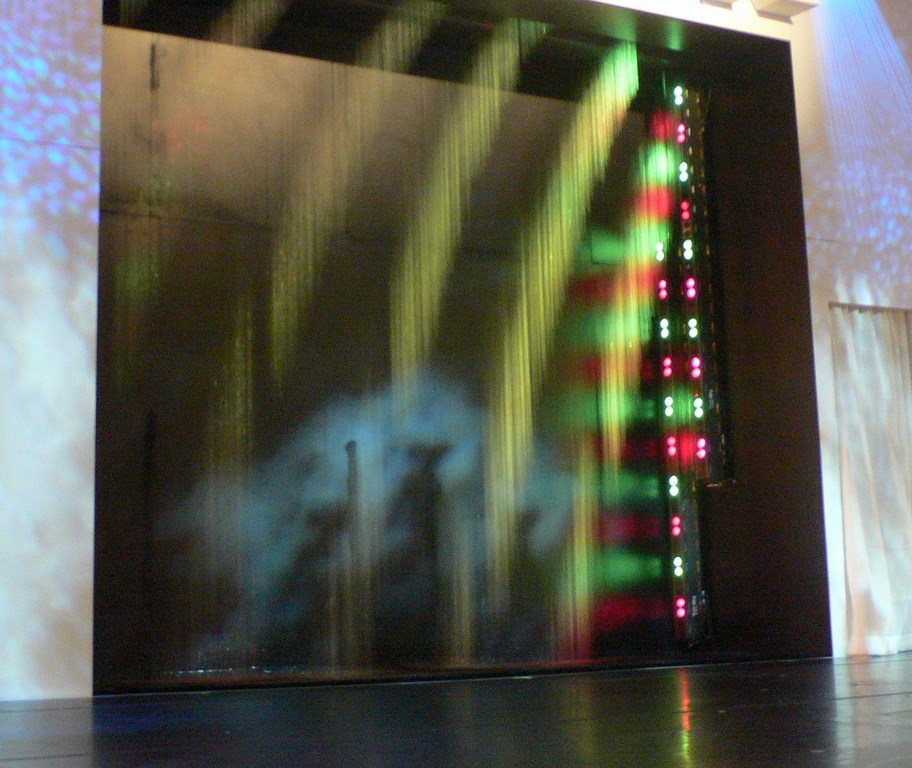

| While many of the displays I develop for use in tradeshows include company logos and brand names, the displays are typically varied and feature graphics, geometric patterns, ribbons and various other shapes to capture eyes and entertain passersby as they absorb the corporate messages. In the display shown here, the aim was to create a colorful, elegant backdrop for in-booth entertainment. |

There are, of course, limitations to what we can achieve with these systems. After all, we’re working with falling water!

In systems installed outdoors, for instance – including the one we set up for the Atlanta Olympics – wind can and does affect the image, moving it from side to side but leaving it both contiguous and legible. Actually, our largest challenge in Atlanta case was making certain we could replace the water blown out of the system so the pump wouldn’t run dry.

This sensitivity means that, as a rule, letters and distinct parts of images need to be at least two feet wide, meaning we can’t be too delicate in our presentations. Also and perhaps more significant, there are settings in which the effect doesn’t show up as well – particularly in places where there’s a light or bright background. (You can’t see images well, for example, against blue sky.)

And ironically, given the fact that the original system was developed using a machine designed to make music, we haven’t ever been able to synchronize my waterfalls to a musical score and have it turn out to be aesthetically interesting, even with the aid of specialized software. As a result, I’ve never set out to integrate a show to music.

Those constraints aside, however, the basic technology behind these waterfalls has thus far stood the test of time.

MAKING THINGS WORK

Units operate in a way that’s similar in some respects to inkjet printers, although there are no moving heads. I like that connection, however, because I’ve always found it useful to consider the droplets as being analogous to pixels and the clarity of the image as being a function of the size of the droplets and water’s surface tension. (The exact size of the nozzles and the droplets is proprietary information, but I do make them as large as possible.)

The water emerges from the nozzles under low pressure, so the rate at which it falls is attributable mostly to gravity. Thus, it is the speed of the valves’ operation that is the critical factor. Mine are actuated with needles that open and close the orifice at a very rapid rate; this is another case in which the way things happen is a closely guarded secret.

| The display we developed to celebrate the 60th anniversary of the reign of Thailand’s king show the technology at its most elaborate – in this case a 24-foot-wide, six-nozzle deep array that presented a variety of effects, including, as seen here, the royal crest and a saxophone (appropriate as the king plays the sax). It also conveyed best wishes for long life in Thai and English as well as dragons and musical notations. |

Lighting is another key to the success of these displays. Although it can be introduced from the top or sides, I’ve always preferred handling it from the bottom. Whatever the angle, I’ve worked with white lights and with colored lights in various configurations of fixtures, and I must say I’m very impressed with today’s LED lights.

Exhibiting indoors allows for better control of lights and lighting. Indeed, exterior placements are a challenge because of the sun and how way ambient light changes during a typical day in ways that make consistency of the visuals an issue. Graphical Waterfalls are rich in “information,” so contrast is important and people want to see more detail in them than they do in traditional fountains. With proper staging, these displays can be viable outdoors, but it’s not easy to do.

|

Self -Direction Through the years, I’ve run into the possibility of expanding Pevnick Designs and the reach of our Graphical Waterfalls by accepting investment capital or merging our operation with another company, but I’ve always chosen to maintain control of our research and aesthetic directions. As I see it, pursuing these opportunities might have the effect of diluting my control or would end up with me being relegated to a role as research-and-development manager for a larger company. This self-directed approach has probably led to slower growth than we might have achieved otherwise, and indeed, when we started out, nobody seemed to know just how much he or she needed one of our Graphical Waterfalls. Through persistence and steady progress, however, we’ve grown through the years and have really hit our stride in recent years, with lots of displays here and in Europe and generation of more media exposure. At each show or event, we run into other designers and get fresh feedback – occasionally of the crazy variety: Lots of people think, for example, that the images are projected onto streams of water, and at one show, someone even asked how I froze the water at the top and managed to melt it before it reached the bottom! — S.P. |

As a rule, the units run with local tap water, and the water is replenished at a rate of about a third of a tank each day as a result of evaporation. (Depending on where we are and local requirements, I’ll use a chemical oxidizer to kill bacteria.) At trade shows, these units run for just a few days and are thoroughly cleaned between uses, so scale buildup isn’t an issue. In permanent installations, however, there’s a need to monitor (and treat) water for mineral content to avoid problems with nozzle clogging.

The units are always hard-mounted to a support structure above an exhibit, which, depending on the structure, requires different types of rigging. No matter the setting, the units create a significant amount of vibration, so the mountings have to be designed to support dynamic loads with minimized vibration.

For simplicity (and given the fact that show displays are not permanent), water flow from basin to valves is handled using flexible vinyl hose with quick-release couplings. That’s important at trade shows and special events: If the connections are of the quick-release type, there’s no need to hire a plumber to set things up.

As specialized as these waterfalls may be, they do share issues with other effects that use moving water. Because they’re installed most often in show booths with carpeting and in tight spaces, for example, managing splash-out is a factor: Exhibitors don’t want their carpets or their shoes to get wet. I’ve tinkered with various catch-basin designs, but I’ve basically settled on using a fine nylon mesh to cover the basin: This can create a bit of mist at the base of the waterfall, but no water escapes once it flows through the mesh.

FORWARD MOTION

My studio these days is a 21,000-square-foot building just west of downtown Milwaukee. There, our waterfalls are researched, built, staged and programmed; sent out to shows; and received, cleaned and maintained after each show. In all, Pevnick Design employs ten and works with two consultants.

| The most ‘visible’ of all the graphical fountains we’ve done to date was this one, set up in Centennial Park in Atlanta for the 1996 Olympic Games. The 110-foot theme tower contained a 50-foot-tall waterfall 12 feet wide and 24 nozzles deep. Millions attended the event, and millions more saw the display on television (that’s NBC’s peacock, as you may have noticed). |

As I mentioned at the outset, I never intended for these systems to make their greatest impression in the world of trade shows, but that’s how it has worked out so far. I’ve always been hopeful that interest would expand and that these systems would find their way into permanent architectural settings – makes sense to me, and these systems would, I think, be great additions to shopping malls, corporate campuses and more. And I would be particularly gratified to see them used as public works of art.

Through every developmental stage, I have always been amazed by the potential of my Graphical Waterfalls. As I see it, surprise and wonder are at the very core of satisfying human experiences, and I see no limits to the creative ways in which this surprising and wondrous technology can be applied.

For me, fashioning these systems has been all about making art from kinetic shapes and forms. Given my experience so far, it’s more than likely the next path we take will be something I’m not even anticipating. And that potential, I think, will be more than enough to keep me going for years to come.

Stephen Pevnick is founder and president of Pevnick Design, a firm dedicated to creating Graphical Waterfalls, a unique system that uses precisely controlled water droplets to form letters, words and graphical symbols. Pevnick has an extensive background in technology and fine arts, including a bachelor’s degree in design and fine arts from Southern Illinois University and a Master’s Degree in multimedia, fine arts and sculpture from Washington University in St. Louis. A professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, he has won a host of awards and grants for his work in developing Graphical Waterfalls. Among his many notable accomplishments was the time in 1966 he spent working for legendary futurist and writer R. Buckminster Fuller. You may find further information by clicking here.