Now Showing

Last time, I described (at great length, as you may have noticed) what happens in the time between my initial phone conversation with clients and a point just ahead of my formal presentation of a design.

It’s an involved process that uses all of the information I’ve gleaned from my clients about what they want, what they think they need and what they ultimately expect to have in their backyard environments. It’s about understanding the underlying circumstances, deciding what should be done and, finally, assembling all of that insight into a

visual presentation they can understand.

This transition from a deliberative/collaborative/conversational process to a final unveiling of a design concept is obviously important: You can create the most elaborate, extensive design imaginable, but if it’s not right for the site or the clients can’t grasp what you’re doing and you haven’t been listening to them, there’s little point in making the presentation: They simply won’t follow through with you.

If everything’s in place, however, you can proceed to the presentation with reasonable expectations that you’ve hit the nail pretty squarely on the head.

WALK RIGHT IN

When each of us works with clients, we all apply our different personal styles and ways of working with people. Speaking entirely for myself, I dress casually and basically present myself as someone who is likely to become a friend in the course of our working together – someone who will have his own special coffee cup in the clients’ kitchen for the duration of the project.

That’s just me, and I appreciate the fact that there are infinite numbers of ways to approach these endeavors. Frankly, I don’t know how to approach people any other way. I am always professional, always dignified and distinctly focused, but my main goal in the presentation meeting (and in most other situations) is to make clients feel comfortable around me and let them know that I’m comfortable with them.

|

Visual Record During one or more of my early visits to a site, I invariably take “before” pictures and begin amassing a visual record of every phase of a project. I’ve done this with every job I’ve ever tackled, even in the days before digital photography made it easy. I do so for several reasons, not the least of which is that it helps me in preparing a design for presentation. It’s just too easy without photographs to look at a site from a bird’s-eye view and forget, for example, the ways established trees influence a site and therefore affect placement of a watershape or other elements of a design. The images are yet another design tool, and a valuable one at that. — D.T. |

At the same time, I make no bones about the fact that I consider myself to be a talented designer and that what they’re getting from me is a work of art tailored to their desires and needs. Despite the sneakers, that prime, overarching fact is reflected in the way I carry myself and in the information I present to them.

As I’ve mentioned before, if the project is for a couple I insist on both of them being there for the presentation – and I like it to happen in the morning, when all of us are fresh and undistracted and there’s greater likelihood I’ll be able to help them “see” what we’re discussing.

I’ve also noted previously that almost all of the presentations I make are based on the thought that I will be the one building the design. This is an important distinction, because it means that there will be a number of things I will not be presenting – namely, all sorts of technical drawings that would be needed to put a job out for bid. I also leave out things like plumbing schematics and complete sets of structural details – that stuff comes later, when and as needed.

My goal in presentations is instead very straightforward: I want them to understand and appreciate the design I’ve developed and get a sense of the interplay of various spaces and structures as well as colors, materials, lines, textures and shapes. At this point, I also want them to have a general idea of what the project’s going to cost based on my best understanding of site conditions and engineering principles.

With this approach, it’s all about simple visualization – not about rolling through layers of documentation that would be needed for someone else to build what I’ve designed.

IN HAND

When I show up for these meetings, I’m carrying a site plan, perspective drawings, some sections, relevant materials samples and a complete breakdown of the project budget based on sets of options we’ll be discussing (but excluding costs associated with the foundation, which can’t be factored in until the soils and engineering work is done).

I don’t believe in bombarding clients with piles of paper and observe that this approach is often used to make up for a lack of quality when it comes to renderings. In my experience, clients aren’t all that interested in the heavy, technical stuff, so instead of trying to impress them by the quantity of paper I can amass, I work instead to capture their imaginations with the beauty and artistry of our ideas.

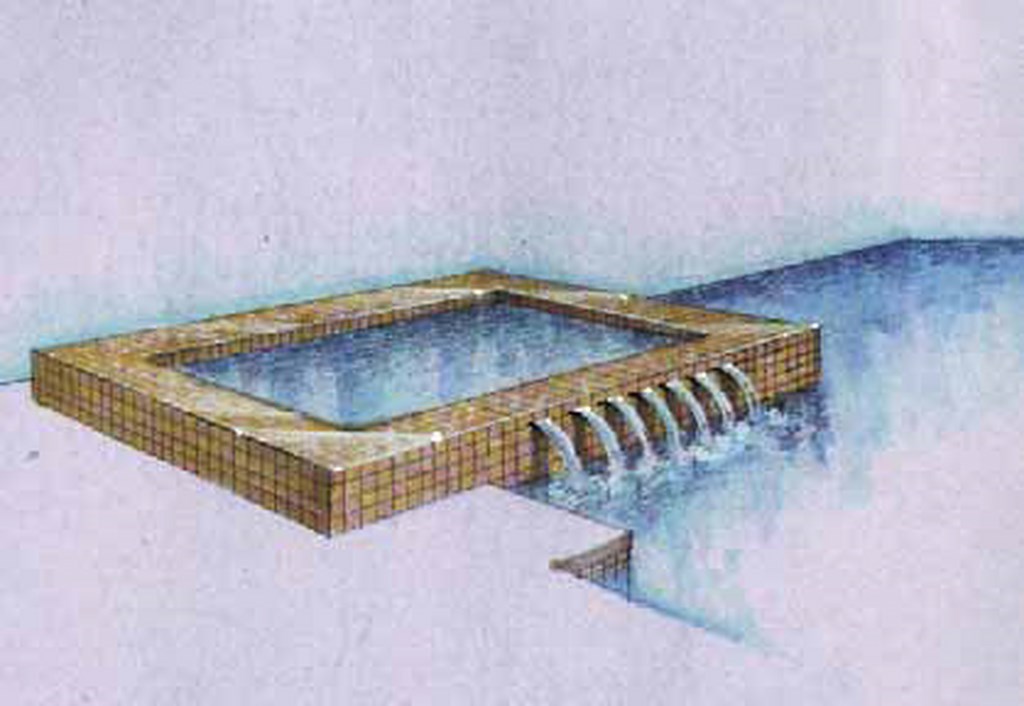

| I always start my presentations with a hand-drawn site plan, rendered in color. Its flat, bird’s-eye view gives my clients a huge amount of information about the basic physical relationships I’ve established for the pool, spa, deck and any other structures that might be involved. Only when they ‘see’ and understand what’s going on in this broadest possible sense do we move onto more specific details in our discussions. |

To that end, the site plan, details and perspective I present are always hand-drawn and done up in color. Not everyone can draw, of course, which has given rise to the use of computer-assisted design (CAD) as a presentation tool, but too often the use of CAD results in flat, sterile drawings that might even be counterproductive when it comes to helping clients appreciate a design and understand what they can expect.

It’s like a lot of other skills associated with watershaping and design. CAD is only a tool, and to use it effectively and flesh out its basic performance with a sense of visual nuance and communicative power, you need training, experience and a real understanding of system capabilities. If you can’t draw, CAD can dress things up, but it will never mask a lack of basic design skill.

| I come prepared with a couple of perspective drawings to give my clients a sense of the elevations and how specific details fit into the overall scheme. On this level, it’s all about giving my clients a sense of what they’ll encounter when they walk into the space. If they have any questions about how things might look if they were, for example, sitting inside this spa or looking at it from the far corner of the deck, I will produce a quick drawing on the spot to meet the need. |

Not to beat the drum too hard, but I know from experience that just about anyone can learn to draw to a reasonable level of competency. And if you just can’t, hire someone who can: I think the difference is that important.

In addition to the drawings, materials samples are a big and important part of my presentations. I bring in color palettes and samples of tile and stone that I’ve determined will be right for the project, usually in a couple forms and finishes – saw-cut, chamfered, tumbled, bullnose – whatever it takes to give my clients a full understanding of the visual power of the materials we’re considering. And I don’t use catalogs: There’s no way that pictures in a brochure can give anyone a true sense of what they’ll be buying.

(To follow up, my clients and I eventually will visit a stone supplier to get a full sense of what’s available, how it can be finished and what sort of variations of color and/or texture might be expected in a large field of stone.)

As for projected costs, it’s important at this point for my clients have a good sense of what we’re doing and how the aesthetic decisions we make from this meeting forward will influence costs. At the outset of the conversation, we may not yet have decided between, say, an all-tile or pebble finish. What we do know, however, is square footages to a degree where I can offer pricing breakdowns for various materials relative to one another and we can begin adding, subtracting, multiplying and dividing.

PERSPECTIVES

It’s important that these discussions be tied to reality rather than generalities. This is not about selling on price: It’s about advancing the design process and making significant choices among a defined set of visual options.

Indeed, there’s a practical side to these cost-related issues. At this stage, we all need a firm foundation for meaningful discussions about what is and isn’t going to be included in the project. On that level, it’s more about balancing the reality of the budget with the aesthetic aspects of the design – an entirely different process of understanding. (For more on the dynamics of this balance, see the sidebar just below.)

|

What Clients Need Through the years, I’ve been accused (probably with merit) of being self-important and arrogant. I can live with that, because I don’t know too many artists who don’t have an uncompromising sense of who they are and what they’re about. The few of us who work at a level where watershaping becomes art should be sure of ourselves. That whole psychology needs to be balanced, however, by the important observation that nobody truly needs a swimming pool. Nor are watershapers counted among those – including doctors, farmers or fire fighters – without whom our society would come to a halt: The hard fact is the world would go on even if we weren’t around to make pools, spas, fountains and waterfalls. What we provide is a luxury item imbued with senses of beauty, comfort, relaxation and pleasure. On that level, everything that artistically inclined watershapers do is related to giving people something they want rather than something they need. Despite that fact, lots of watershapers try to persuade clients to want items that they do not need and, when you get right down to it, don’t really want. For my part, I would rather offer a system devoid of bells and whistles and instead put the value in assembling design elements that are truly suited to my clients and the site. You can make a spa so complicated, so loaded down with features that the client may never be able to figure out how to use them all. I’d rather keep things simple, using water effects that fit the site and the clients’ desires. In other words, it’s not about packing a job with bells and whistles or worrying about leaving money on the table: Rather, it’s about exercising restraint and common sense and delivering a design that’s both appropriate and aesthetically pleasing. This is why design presentations are so important: They enable us to zero in on our clients’ value systems and assess their desires and wants. On that level, it’s about inspiration and passion, not about coming to the table convinced that a perimeter overflow or vanishing edge is indispensable. As I’ve been told, often it’s what’s left off the page that makes the brushstrokes we do employ truly beautiful. — D.T. |

With all of the visual presentation materials I provide, my prime objective is to get my clients to understand the way the watershape and other design elements work together in the context of the site. This is why I start off with a highly detailed flat plan: It’s bird’s-eye view shows the basic physical relationships I’ve established among the pool, deck, overhangs and other structures.

Once an adequate sense of the way things are arranged sinks in, we move on to the perspective renderings, which show the design from key focal points and enable my clients to grasp what they’ll see when they walk into the space. These sheets give them a sense of the way that the structures work within the contours and elevations on the site.

This is where being able to draw on the spot comes in handy. Often, for example, clients will ask what something’s going to look like from a reverse angle, how something will appear while they’re sitting in the spa or how certain intersections of materials will work. I am prepared, in other words, to meet specific questions with specific and helpful answers.

Moreover, in conjunction with the sample, these drawings give my clients a taste of what’s to come with respect to color palettes, the textures of various materials and the general role of landscaping. (I’m not a landscape designer, so I never get down to specifics; rather, what I show is the way planting beds interact with the pool and other hardscape or structural details.)

Once we roll through this basic conceptual overview, we get down to specific details and sections – information on key project elements that I want them to understand, such as the way the coping and the surrounding deck will interface, for example, or how we’ll hide the skimmer lid.

In all cases, I have blueprints on hand that we can mark up during our discussions. This allows us to refine the design face-to-face and helps me later on if I need to make changes when I return to my studio. I also usually have some simple sections on hand so we can discuss basic structural details – but it’s important to note that these are for illustration only: I never represent anything I’m showing them as “structural design.”

BOTTOM LINE

Through the years, I’ve found that this combination of flat plans, perspective drawings and materials samples is generally all it takes to enable us to talk and think in three dimensions and pull everything together in visual terms clients can understand. The goal is simple: I want my clients both to visualize the setting and appreciate what they’re getting.

When the complete picture unfolds, issues of price don’t disappear, but as a rule, by the time we complete our discussions they’re able to see a greater value in what we’re about to accomplish. They have, in others words, come to see what we’re doing as the pursuit of a work of art.

|

Finding Inspiration When I was teaching students to draw at UCLA, a colleague of mine said something very wise: “None of us will ever need to reinvent the wheel. Through our drawings, however, we can refine it.” I’ve always thought of myself as someone who fits into a long heritage of basic concepts that can be intelligently refined through design. This is why, in virtually every article and column I write, I credit the architects, designers and artists whose work has inspired me and whose ideas I have done my utmost to refine in my own designs and presentations. I see this kind of credit being extended by more and more watershapers who contribute to this magazine. I applaud the trend and encourage those who make it into print always to give proper credit to their sources of inspiration. Truth be told, I wouldn’t object to getting a bit more credit for ideas I’ve developed and refined through the years. Hugely more important, however, I am convinced that if we all identified where our ideas came from as a regular practice, we all will benefit as designers by opening new wells of ideas. Bottom line: The pace at which watershaping is emerging as a distinctive, energetic form of art will only accelerate into the future. — D.T. |

Most of the time, when I’ve finished my presentation and have completed a run through the drawings and samples, my clients simply say “It’s beautiful” and we’re good to go.

That’s my goal: No matter what specific discussions we might have about what features might go into a spa or which type of stone detail we’ll use on an edge, I want them come away with the thought that what we’re discussing is a beautiful piece of artwork.

I take great pride in the face that many times, long after a project is complete and I visit to check on how things are going, I’ve see the renderings I’ve done framed and hanging in my clients’ homes. This speaks volumes, telling me that the clients value the design itself.

And when they’ve come to see the work I’ve done in that light – as a work of art – they naturally place a greater value on the reality they see outside their back door.

It all goes hand in hand: Their ideas, my presentation of design and the product of our endeavors all come together in a beautiful environment that makes them happy and proud. It’s the culmination of a process that begins with our very first conversations, and it’s in the presentation of the design that they initially get the sense that they’re working with me to obtain something no one else has.

But I get ahead of myself: Between the presentation and the warm glow of satisfaction come a number of other important steps, starting with permitting and engineering – our topics next time.

David Tisherman is the principal in two design/construction firms: David Tisherman’s Visuals of Manhattan Beach, Calif., and Liquid Design of Cherry Hill, N.J. He can be reached at [email protected]. He is also an instructor for Artistic Resources & Training (ART); for information on ART’s classes, visit www.theartofwater.com.