From the Beginning

Why isn’t the appropriate use of water a defining, central component in the education of landscape architects?

That question has rattled around in my head for a long, long time, basically because it has no adequate or satisfactory answer. I’m a trained landscape architect and, as luck would have it, for nearly 20 years I’ve had one foot in the pool industry and the other in landscape architecture – and I’ve always felt like a rare beast moving back and forth between two entirely separate worlds.

As I see it, this lack of affinity between these water-related industries has been a limiting factor in the advancement of the watershaping trades. For me, the lack of connection has always seemed nonsensical when it hasn’t seemed tragic.

As a watershaper, a big part of my work in recent years has been seeking ways to combine the best of both worlds and share what I know with university-level students in landscape architecture departments – students whose chairs I occupied some years ago and who still stand a good chance of graduating without ever having been taught anything at all about how water can

best be used in the environments they will be designing.

It’s a gap I feel compelled to fill by every means at my disposal.

FACING THE VOID

A longstanding frustration has been that only a few information sources have ever sought to pull these two related disciplines together – WaterShapes being one of the few. The reality is, absent undergraduate studies that serve to bridge the gap, the magazine fairly well stands as a lone voice in a field otherwise defined by silence.

As a first-year student in a landscape architecture program, I often asked my instructors when we would learn about pool and fountains. It made sense to me that we would, because I was working for a pool contractor at the time and saw the immediate, visceral connection between what I was doing professionally and what I thought I should be learning as a student.

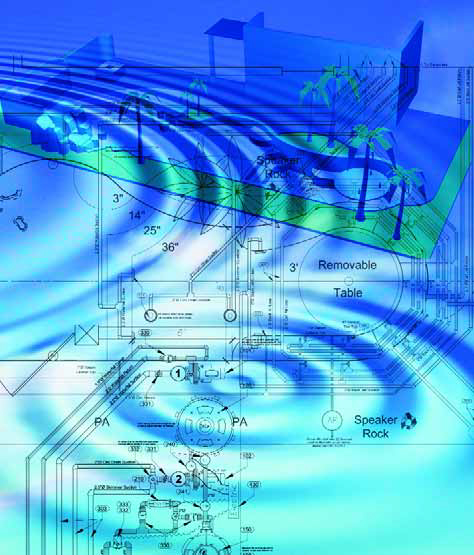

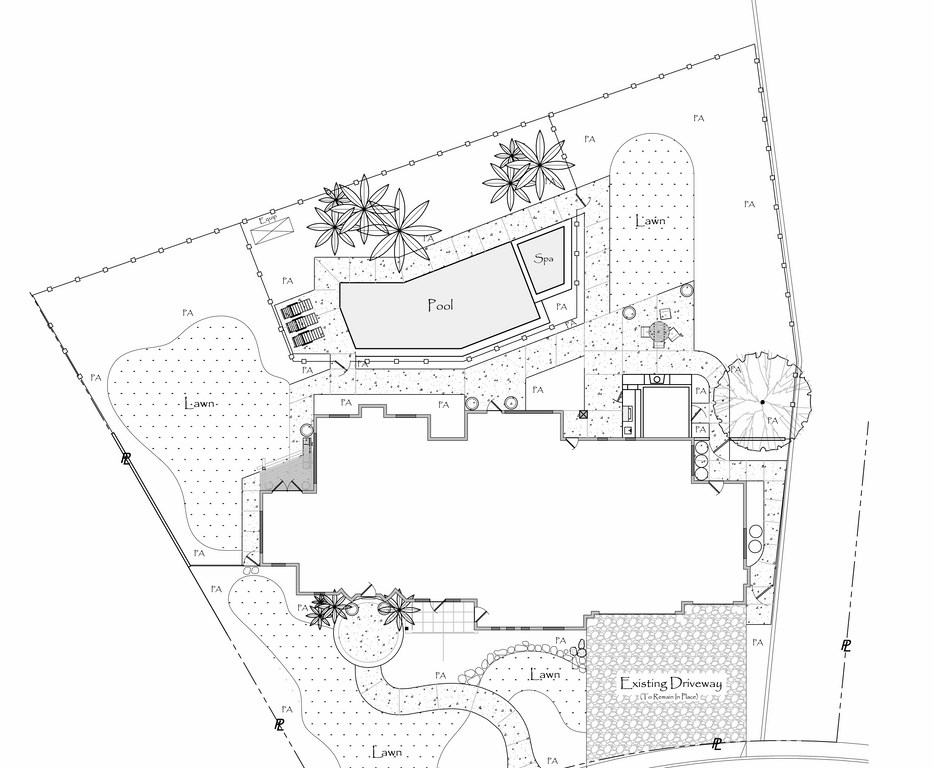

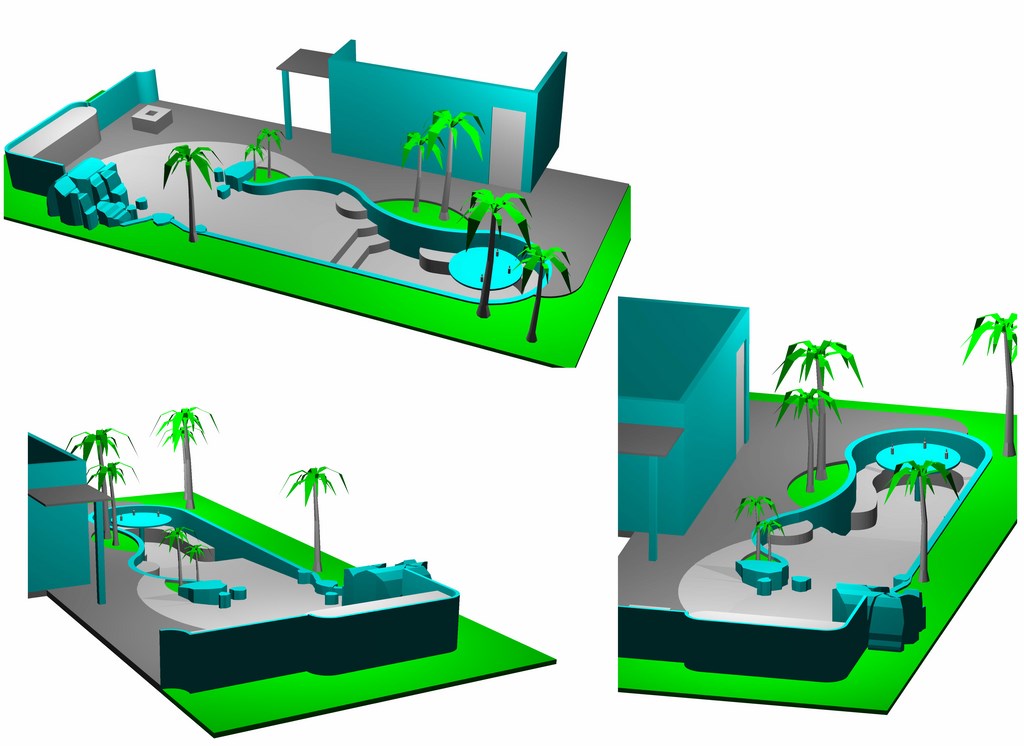

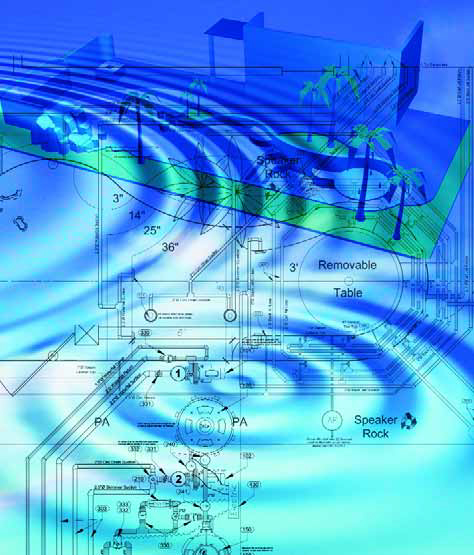

| All too often, landscape architects unfamiliar with the technical detailing of watershapes will relinquish control of that part of a project, gracing an otherwise elegant rendering with a detail-free suggestion of what a pool, spa or waterfeature might be – if, that is, someone else takes charge and figures things out. One of the goals of my new course is to dispel the mysteries of watershaping and equip future landscape architects with the tools and information they need to complete their designs with watershapes that can actually be built. |

Every time, however, the response came back that there was no formal water instruction for landscape architecture students. That response made me dizzy, and I recognized quickly that as a new student I knew more about water and its uses than most of my professors did or ever would.

The odd thing is that landscape architects are expected, both by the industry and general public, to be the stewards of ornamental water. The sad truth is, with very few exceptions, that these well-educated, well-qualified professionals lack any formal education in the arts of watershaping.

Indeed, in the context of landscape architecture, watershapes are typically designed, engineered and built by contractors and/or a handful of knowledgeable consultants who have been asked to interpret concepts outlined by these landscape architects. This leads to a wide range of challenges, not the least of which have to do with the language and vocabulary that reside at the very heart of watershaping.

The result is that developing an understanding of what it means to work with water has, for landscape architects, come slowly to most – and only as a result of experience rather than education. In an attempt to close this chasm between design and construction, my own firm, Holdenwater (Fullerton, Calif.), works for both landscape architects and builders and has established a set of standards we work by – rules of design that cover everything from hydraulics to standards of graphic presentation.

Again through experience rather than education, I’ve come to believe that these standards are very close in nature and scope to what any landscape architect should apply in his or her water-related design work.

THE STATUS QUO

The educational currents in landscape architecture have always tended to lag behind actual industry practice, sometimes quite significantly so. At this point, for example, the dominant portion of study time is spent learning quite a bit too much about civil engineering and such issues as road alignment, surveying and regional watershed calculations in seeming defiance of the real world into which these student/designers will someday be thrust.

It’s not that they need complete expertise – indeed, despite their training, landscape architects have been hiring civil engineers as subcontractors for decades. What they really need is familiarity with the basic practical vocabulary of these trades along with some direct, practical exposure to structural and geo-technical engineering, cost estimation, environmental psychology and, most important in this context, the design of ornamental watershapes.

| There’s no reason at all why landscape architects should be allowed to graduate from their programs without knowing the ins and outs of watershaping right down to understanding (and even mastering) details of plumbing and equipment specification. These project components are just too important to be left to chance. |

Despite the obvious need, educators designing courses have reflexively ignored issues and areas of focus that those of us working in the water world know are so clearly needed.

It’s my conviction that when water studies become mandatory for landscape architecture students, the watershaping industry will start to be taken more seriously in the broader universe of design professions. Moreover, landscape architects will stop asking builders and consultants to design their watershapes – a win-win situation if ever I’ve seen one, as builders will finally be allowed simply to build and landscape architects will be equipped to give them the documents they need to get the job done.

|

Open Ears For many years now, WaterShapes has offered me the ideal environment for presenting my beliefs and reaching out to both the design and construction trades. I’ve also come to see this magazine as a vehicle capable of driving the next step in the evolution of landscape architecture, but it’s my sense that I should not be pursuing this mission alone: As we compile and publish this series of articles, I invite any professional to contact me or the magazine with their thoughts and ideas on how landscape architects can become better watershapers. It will all happen faster if we do this together. — M.H. |

Consider how often pool contractors receive sets of plans from landscape architects that have no more than a ghostlike shape with the word “pool” attached to it and, at some distance away, another mistakenly sized box labeled “equipment.” To builders, this is a realm in which the divide between design intent and execution is at its widest. This is where variations in pricing and bids are rampant, because so much is left to interpretation and guesswork.

In my book, every landscape architect should be able to detail every fitting of a circulation system (including sanitizing components) down to every fitting and valve in the system. At this point, however, there is nothing in their pool or fountain designs that comes anywhere close to addressing these sorts of practical requirements. Lights, steps, tile specifications and a great many other specific issues are left entirely up to contractors who most likely will install what is readily available in the absence of more specific guidance.

This is where consumers’ faith in the entire watershaping industry is most seriously compromised: The result is apples-to-oranges bids and client questions about why the costs vary so widely. The overriding problem is that there are no specifications to bid, therefore no common ground or vocabulary. This can and must change.

MAKING HEADWAY

At this writing, no four-year university program offers any formal, long-term curriculum in watershaping, but a number of concerned professionals have endeavored through the years to introduce designers to the technical specifics and artistic nuances of watershaping through classes and workshops.

Perhaps most prominent are the schools and classes offered by Genesis 3, but there have also been occasional courses I’ve offered at universities including California State Polytechnic University at Pomona, where I went to school many years ago. These are wonderful programs that have advanced the industry, but they are not sufficient, I think, to advance a dedicated, thorough watershaping agenda.

Even in these limited settings, however, several of us have started initiating designers to their need (in fact, their responsibility) to specify products and truly design the guts of their watershapes. Along the way, a need for a more formal set of standards has emerged – principles that will tie the whole watershaping industry into a standard, repeatable approach to the design and construction of watershapes.

At Holdenwater, we follow a set of what we call “commandments” as we prepare construction documents for a designer’s watershapes – a simple list of guidelines we apply to every watershape we develop and that can be used by any design professional working with water. These guidelines include basic steps that assure landscape architects and all other watershape designers that they are providing their clients with a valuable, reliable service. They include:

[ ] Design Research: We embrace historical precedent and the work of past designers and apply an understanding of how humankind has manipulated water throughout history.

[ ] Site Analysis: We research, document and analyze all pertinent site criteria as a means of guiding the design to appropriate solutions.

[ ] Water Dynamics: We design and fully communicate all expectations having to do with how water flows and behaves in any waterfeature.

[ ] Feature Classification: We indicate if a project is public or private and then consciously decide whether or not the watershape will be for bathing, and if not, whether it will be a biological or sanitized system.

[ ] Materials: We fully specify all materials and are completely aware of their reactions to and performance in water environments.

[ ] Budgets: We have a basic understanding of the limits of available funds for any given element relative to project scope and expectations.

[ ] Safety: We establish a concern for human life, safety and well being as a prime directive that rises above every other factor in designing a watershape.

[ ] Engineering: We solicit, are aware of and heed all recommendations offered by geo-technical, structural, mechanical and electrical professionals.

[ ] Longevity: We make a significant effort to design features and specify products and services that will ensure our watershapes will have a longer life spans than their designers.

[ ] Construction: We never allow a contractor to build or value-engineer any design without providing them with full construction documentation ahead of time.

[ ] Design Consultants: We retain licensed design professionals capable of handling any and all aspects of watershaping that we cannot handle ourselves.

Each of these points is important in its own way, but all are needed collectively to complete watershape designs with any significant assurance of competency.

The default for every professional is the last item: When you don’t know what you are doing or sense that a project needs something you lack, call on someone who knows better. As a landscape architect, I frequently rely on surveyors and geo-technical and structural engineers. Hiring a watershaping professional should be no different – Holdenwater’s sole mission is to be just that sort of resource – and this is where the education of landscape architects comes fully into play.

BY EXAMPLE

In our firm, we consult and teach with every project we pursue. This way, the designers we work with start to feel comfortable with water and will use it more often because they’ve learned which questions to ask and, more important, know more and more about what constitutes “quality design.”

As I see it, the education of landscape architects and their increased proficiency in watershaping is beneficial to every associated trade and industry: There is nothing harmful about making landscape architects better and more thorough designers – unless, perhaps, your current business model involves taking advantage of their professional inadequacies.

| My belief is that this need for practical watershaping skills among landscape architects reaches out in all directions – not only when it comes to communicating on site with contractors who will execute the work according to plan, but also in understanding elevations and materials and rendering them in ways that facilitate communication with clients and crews alike. |

As I write this first installment in what will be a lengthy sequence of articles, I am also preparing to teach a new class at Cal Poly Pomona that will be part of my old school’s four-year program for undergraduates earning their degrees in landscape architecture. So far as I know – and please let me know if I’m in error – this is the first such course offering of its kind anywhere in the United States.

In this setting, we will be taking landscape architectural students through the guidelines listed above while shedding additional light on the dynamics of the watershaping industry. The goal here is to prepare a substantial group of designers to move into the real world armed with the tools and resources they need to create intelligent designs with water.

My hope has always been for specific water-related education to become a component of every environmental design department in the country, and my intention in preparing these articles is to create enough momentum that a dream can become reality. Students want this information, and the industry wants and needs them to have it. The time is now for our educational institutions to step up and join in watershaping’s growth and development.

This series will, I trust, help all of these processes on their way.

Mark Holden is a landscape architect, pool contractor and teacher who owns and operates Holdenwater, a design/build/consulting firm based in Fullerton, Calif., and is founder of Artistic Resources & Training, a school for watershape designers and builders. He may be reached via e-mail at mark@waterarchitecture.com.