Design Time

When I sit down with clients for our first face-to-face meeting, we discuss a range of issues that will guide me when I return to my studio and get down to designing a watershape and surrounding areas for them. We’ll talk about colors, materials, the location of the pool, their preferences in art, the way they entertain and, perhaps most important of all, how they plan to use their backyard and swimming pool.

Let’s focus on that last point: When we talk about how a pool is going to be used, what I really want to know is how it will be used on a daily or weekly basis (for swimming, exercise, play or simply as a visual), not how it’s going to be used once or twice each year when they throw a big pool party. My thought is that these clients will

live with their watershape constantly, so the design needs to work for them every single day.

If I don’t pursue this point, I know my clients will in some way be disappointed. As a result, I do all I can to consider the everyday aspect of the program, begin offering some carefully qualified ballpark figures on cost and know from experience that these discussions will affect all aspects of the design, from the materials we select and the configuration of the steps and benches to the placement of the pool and the provision of shade structures, cooking areas and myriad other details.

It all comes into play, which is why I need to have so much information in my possession by the time the initial meeting ends and I head back to my studio. Using an analogy suggested by my good friend and fellow watershaper Paul Benedetti, it’s time to stop dating and get engaged.

CRITICAL STRUCTURES

By the time the initial meeting ends, I have established the need for the clients to obtain soils and geology reports, referred them to two or three experts who perform such studies and left them to follow up. Once they’ve shown their commitment by making arrangements to have the studies done (not to mention having received, reviewed, approved and signed a contract as well as submitting a deposit), I begin preparing architectural drawings for their review and acceptance.

Satisfied with their commitment, I start talking with my structural engineer. At this point, the design is far enough along that surface elements can all be developed with some precision – the shell, the decking, shade structures and the like. What can’t be known at this point is what sort of sub-grade support any or all of these design elements will require: For that, we need the soils reports.

The reason I jump into the structural engineering tasks before the soils and geology reports are ready is simply a practical matter of timing: There’s usually a three to four week waiting period in my structural engineer’s office, so hanging on until everything falls into place would prolong the project unnecessarily. It’s a shortcut, but it’s not a risky one.

Once the soils and geology reports come in, my first task is to submit them to the governing municipality for a letter of approval – a process that can take anywhere from three to seven weeks, for example, when I work in Los Angeles. Once that process is under way, I take the reports to the structural engineer as well: Now the final structural documents can be prepared using all available information about the soil conditions and what sort of support the various structures will require.

|

Borrowed Expertise As anyone who reads my “Details” columns knows, I’m an opinionated guy. One of the areas in which my opinions are strongest has to do with structural engineering, which I consider to be of the greatest possible significance in successful watershape design and construction. I have seen plans designers or builders have given clients in which there has obviously been no input from a structural engineer. Instead, what these builders offer is sheet after sheet pulled from books of standard details – maybe a dozen or even two dozen impressive-looking sheets that bear no direct relationship to the project or the soil conditions at hand. Instead, what the clients get is guesswork and supposition that rarely have anything at all to do with the site itself. To me, this is criminal behavior: Only a licensed structural engineer has any business acting as one, and the willingness of some builders to cut corners and avoid the expense of consulting with an expert almost certainly explains the startling failure rate of concrete watershape structures. To have any value at all, structural plans must be site specific. I say for this reason that one of the most important aspects of my design work is something I don’t do. My strength is creating designs that inspire my clients and occasionally rise to the level of art, but for all of my experience and background in design and construction, I am not, nor will I ever be, an engineer. If I offer clients three or four details for key features such as steel in steps to manage shrinkage or for a widened dam wall to handle spa jets, that’s a lot. But I back up the basic plan I offer my clients by working closely with the structural engineer to make certain we’re on the right path and that the construction documents that are being developed clearly reflect the design’s intentions and the clients’ desires. When I’m in California, I work with the staff at Mark Smith, AIA (Tarzana, Calif.), including Mark Smith, Jay Shniderman, Ron Soderstrom and Bill Bragg. When I’m on the East Coast, my choice is Rich Mullins of Damiano & Long (Camden, N.J.). I once had a client who insisted I use his structural engineer. Although a fully qualified professional, the man lacked any expertise in pool construction and working with him was an absolute nightmare. I will never put myself through such an experience again. If you take nothing else from this discussion, I implore those of you who develop your own structural details without an engineer to change your practices right away. Padding your presentations with standard structural details won’t cut it: You are hurting our industry, deceiving your clients and should be ashamed of yourselves. — D.T. |

These early stages of the process take weeks and involve lots of give and take and cross-talk: The municipality, for instance, can request clarifications at any time as it asserts its control over such issues as setbacks, daylighting of slopes and OSHA requirements; the structural engineer needs increasingly detailed guidance on exactly what we’re after; and I need to communicate effectively on at east those two fronts while keeping the clients apprised of any basic changes that need to be made or any revelations that will influence the sort of ballpark figures we’ve been discussing.

Once the dust settles, the structural documentation goes back to the geologist for review and approval, then the whole signed package goes back to the municipality for plan check and permitting. At this point, I am in complete charge in the event any additional information or clarifications need to be exchanged. I do not use plan runners for this purpose: I need to know exactly what’s happening in these crucial last phases.

While all of this is going on, I continue to pursue the formal design process by putting ideas down on paper in ways that will help my clients visualize their project’s potential. In most cases, this means that I’ll prepare two to four pages of illustrative information – basically, architectural details for the project’s main, permanent structures.

These are not structural details, and that’s an important distinction. Many of my projects include overhangs or shade structures, for example – elements that can be designed in any number of ways with crowns, perlins, plant-ons, spacers and any number of other visual elements. As the designer, I will make those architectural decisions and know what the spans are, but it will be a structural engineer (not me) who will determine the size of the required timbers (or, if reduced timber size is desired, of the wood-encased steel) as well as the dimensions of the bases or support structures.

I shepherd all of this information through the process by way of preparing for actual construction. When the municipality finally signs off, we’re ready to go.

NO GUESSWORK

Although I’ve defined the process so far as a sequence of separate steps, there’s a fluidity to design work that comes through most clearly when it’s time to put pencil to paper.

In other words, somewhere in the back of my mind (and often right up in front), I’ve spent a good bit of time rolling through possibilities, refining and visualizing details and generally preparing myself to perform for my clients. I’ve known for quite a while how the pool and backyard are going to be used, who’s living in the home and where the watershape will be located on the site. I also have a strong sense about materials selections, overall aesthetics and the specific details the clients have said they want or don’t want.

What I do now is let all that information guide me – and I have to say that I’m so well prepared that the drawings usually emerge freely and quickly when the time comes.

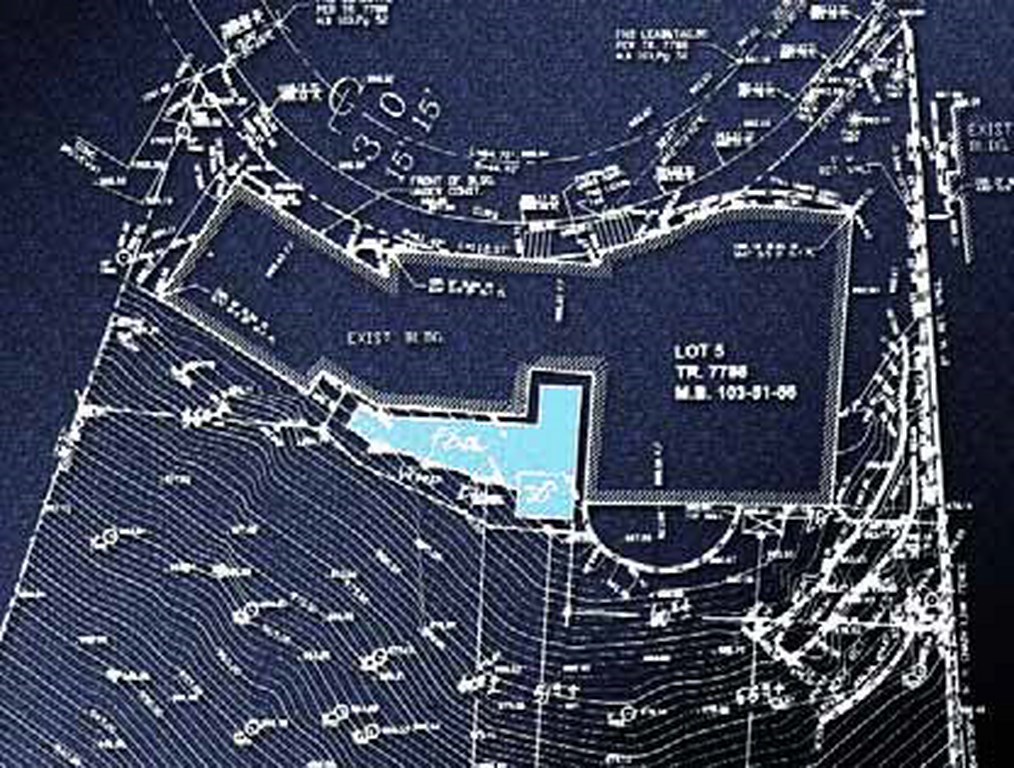

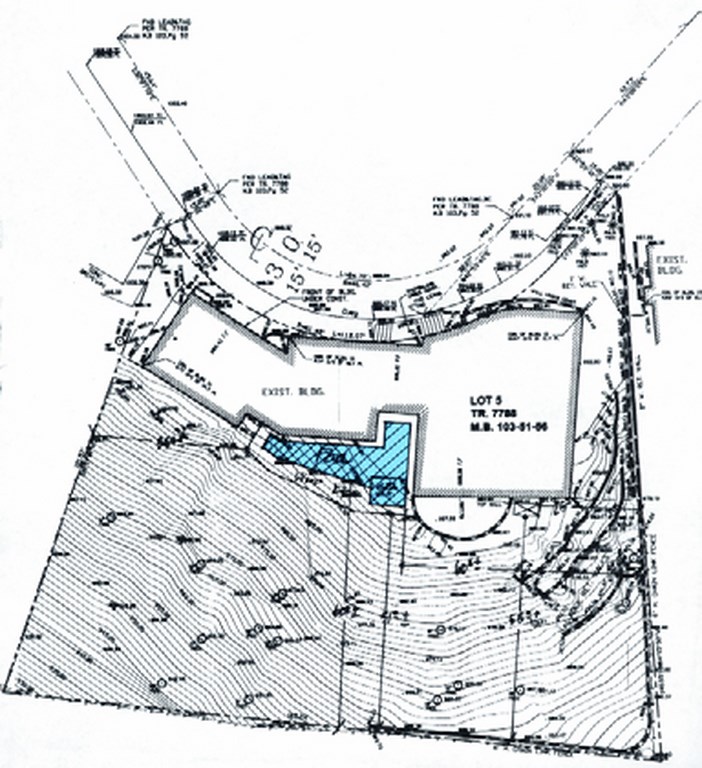

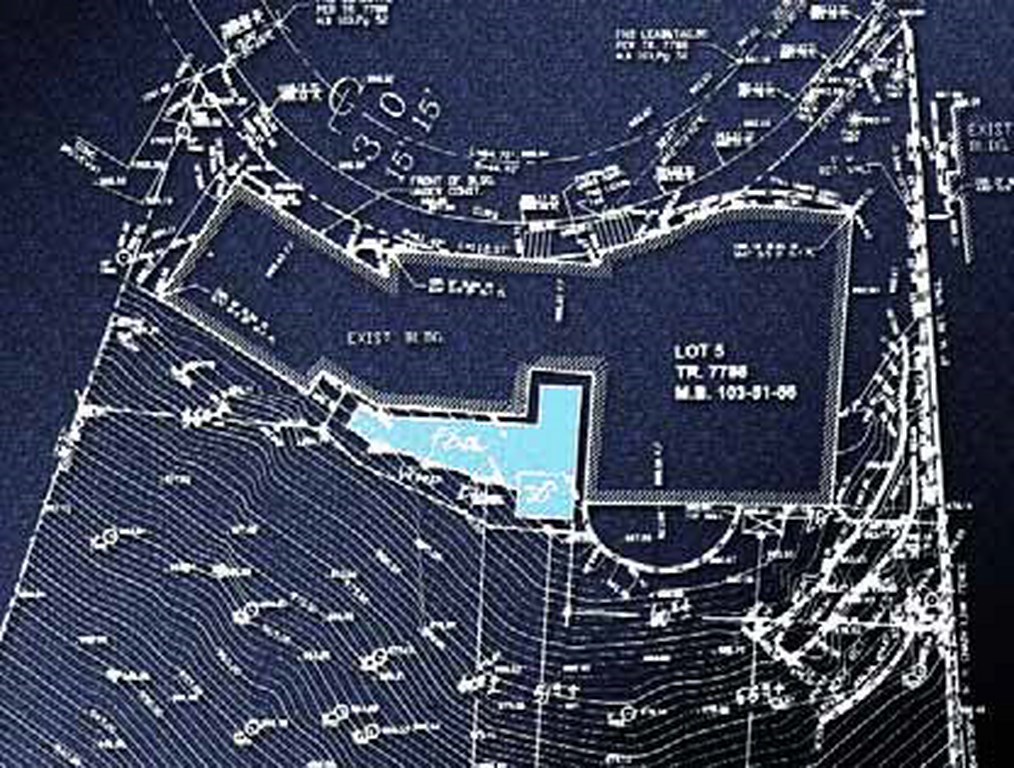

| Among the many things I make clear to clients is the need for basic site information. This includes full soils and geology reports as well as detailed topographic surveys such as the one depicted here. This information is always important to me – but it’s absolutely critical when it comes to proposed hillside construction. |

This directness is made possible by all of the pre-design work I’ve been describing in recent “Details.” If you don’t have that stock of information at your disposal when the time comes, you’re going to end up guessing about what your clients desire, and chances are you’ll generate something that won’t work to their satisfaction.

My own work in this scheme of things is greatly enhanced by the fact that I can draw – a point I’ve raised many times through the years. In meetings, for example, I’ll often start sketching out rough ideas in perspective to help clients visualize the details we’re discussing. As I see it, this is a great way to push ourselves past any obstacles on the path of clear communications.

On a recent trip to Mexico, for example, a developer and I were discussing his need for pools and outdoor kitchens for a large condominium complex, but it was clear he wasn’t visualizing or understanding a key detail I was trying to describe for him. I used an hour-long break in the meeting to retreat to my room, where I used a pad of paper, a pencil and an envelope that served as my straightedge to draw up a rooftop pool that was to be duplicated on each of five buildings as well as some other elements we’d covered.

When the meeting reconvened, I used the drawings to help the client envision the possibilities. No torrent of words would ever have been able to do the job: He just didn’t “get” it until the drawing clarified things for him – and he was hooked.

This is not the same as creating a design in clients’ living rooms – the sort of “sketch” volume builders will turn into a proposal that must be signed that evening. Instead, these in-the-moment sketches are strictly for discussion purposes, and when clients respond favorably to an idea they’ve seen me rough out on paper in front of them, I know that’s an element I’m probably going to include in my formal design work.

SYNTHESIZING DETAILS

Drawing is a big deal to me, which is one of the reasons I’m not a big fan of computer-assisted design (CAD) systems.

If you really can’t draw and you’re doing the right things and have been asking the right questions, CAD might be an effective way to work around your lack of skill with pencil and paper. In my experience, however, almost anyone who applies himself or herself to it can learn to draw to some degree or other – maybe not to the highest standard, but at least well enough to get by in a client meeting. It’s worth the effort, I think, and you’ll be surprised how much this ability can help you work through key issues with clients in a speedy way no CAD system ever will match.

However those issues are resolved, once all of this information falls into place I move into my studio and compile all of my sketches and notes – anywhere from two to five pages of detailed observations – and start refining preliminary ideas into an actual design at the same time the geologist is evaluating soil conditions.

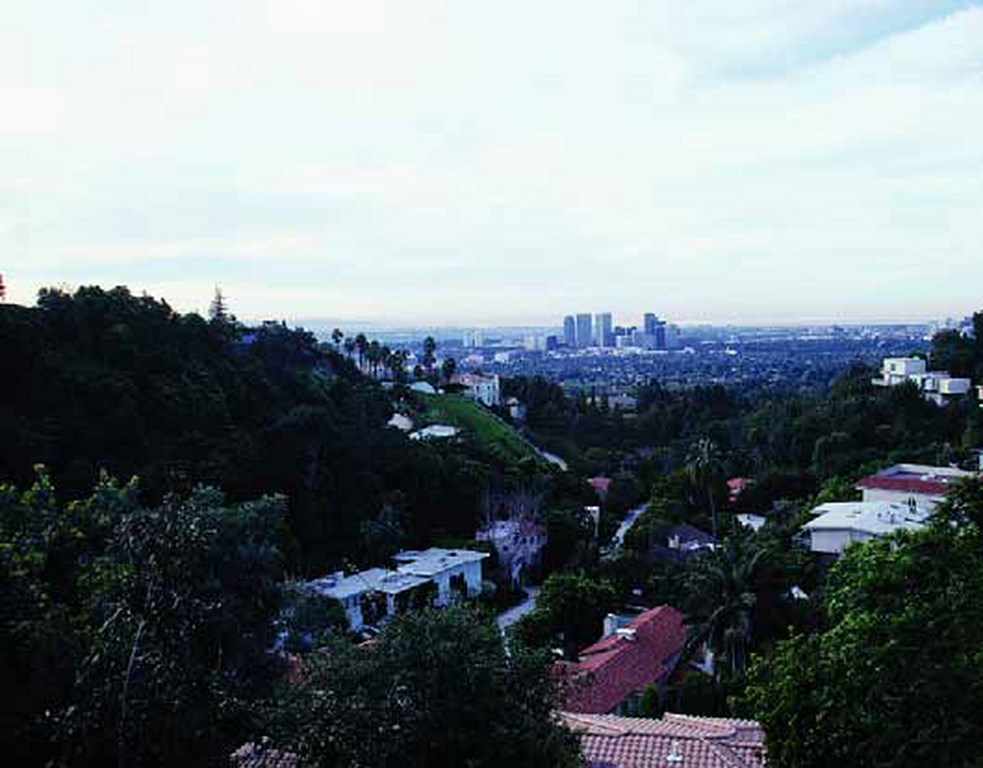

| In my initial client meetings, I pay considerable attention to the architecture of the home and the way it is furnished as well as the views (if any) that the site offers. In this case, the home’s modern style inside and out was a design-guiding factor – as was the billion-dollar view from a prime slice of hilltop real estate. |

This is when I start thinking seriously about scale, proportion, line density, texture, key focal points, materials, color palettes and architectural details such as coping and edge treatments. But it’s not at all like shopping at a “design supermarket”: I don’t walk down an aisle of possibilities and decide I want to use a cover and a vanishing edge and a fountain and tile and a pebble finish and 16-jet spa and a list of other elements I’ll eventually weave into a design. Rather, I compose each project from scratch, inventing a solution tailored to the site and the clients’ particular needs. It’s about invention and innovation, not selecting among a stock set of goodies.

So far in this discussion, I have focused mainly on clients and have not mentioned site issues – but now’s the time in the process when the site itself becomes a major (if not the major) factor. Let me illustrate how important the physical setting can be by considering whether a pool should have a vanishing edge or not.

Let me start by observing that, as wonderful as these effects can be, they are often misused, basically because designers have failed to consider a site’s constraints. In fact, vanishing edges may be the greatest phone-it-in, knee-jerk design solution of the past decade: If a pool is on any sort of slope at all, the temptation to use a vanishing-edge detail seems irresistible, even where it’s not the right move.

In aesthetic terms, vanishing edges work best when they lead the eye to a vista of water or a view or reflection of a beautiful landscape, either in the distance or near at hand. All too often, however, what they end up accenting are views of nearby rooftops, and that’s just wrong. (It leads me to suspect the industry is addicted to these treatments mostly because they drive up the cost of a project.)

My point is, a designer needs to think these site issues through with great care: If the view to which a vanishing edge calls attention isn’t the greatest, restrain yourself and do your clients a favor by pulling the focus back into the yard itself.

Basically, you need to be honest with yourself about what’s right for the setting. When you are, oftentimes you will find that vanishing edges (or perimeter overflows or large waterfalls) are not the best option. As elaborate as some of my projects can be, the fact is that great design often calls for great restraint and a sense of propriety in selecting which elements I’ll use – and which I’ll leave off the page.

IN THE STUDIO

At this point, everything starts coming together. My first task at the drafting table is developing a site plan – that is, an overview of the entire project. This rendering is an extremely straightforward page of information that shows my clients where the elements of the composition are located, their sizes and relationships to existing structures and lot lines, their elevations, the materials to be used and various material transitions. (See much more on these presentation materials in my next “Details.”)

It’s always helpful in getting started if architectural plans of the house are on hand. Many of my clients live in custom homes, so this information is commonly available and is a big help. Nonetheless, I always make it a practice to confirm measurements, just in case. I also shoot the site with a manual building level relative to fixed point to make sure I have the topography right.

Throughout the process – when I’m talking to the clients, suggesting details, looking and measuring the site and sitting at my drawing desk – I’m constantly visualizing the work in my mind’s eye.

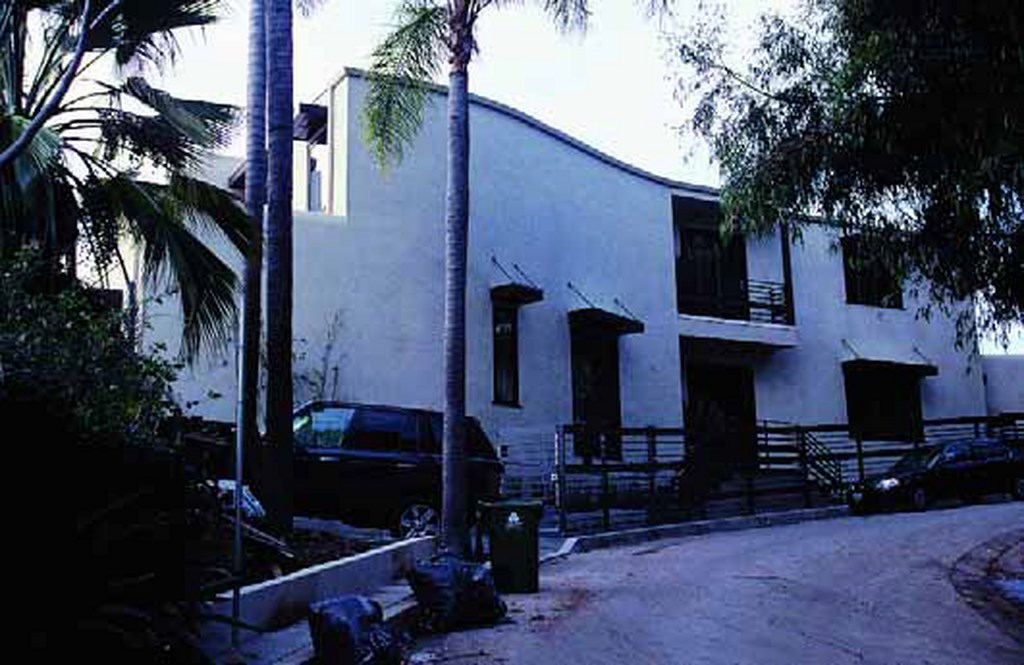

| Once on site, I evaluate all sorts of practical issues related to the construction process. In this case, I noted that access was obviously going to be an issue: The narrow strip along the side of the house would see lots of traffic as the project moved forward and we installed the massive structure that would be needed to support the pool, spa and decks we were to build. |

There’s a tendency to think of visualization as a vague, intuitive exercise, as though there’s some sort of mystery to it, but I don’t see it that way. Visualizing a design is a deliberate process that’s based on education and experience, and it takes practice: You need a firm understanding of how everything in a design works together, how materials will intersect, how things will look from key points of view, how things will balance visually, the role light will play with the materials and the water, how plants fit in – and literally dozens of other details and elements.

There’s a tendency to think of visualization as a vague, intuitive exercise, as though there’s some sort of mystery to it, but I don’t see it that way. Visualizing a design is a deliberate process that’s based on education and experience, and it takes practice: You need a firm understanding of how everything in a design works together, how materials will intersect, how things will look from key points of view, how things will balance visually, the role light will play with the materials and the water, how plants fit in – and literally dozens of other details and elements.

This stands in sharp contrast to builders who will come in and build a shell, then abandon the homeowner to take care of the rest with assorted subcontractors. The shell may be competently done, but it has been completed with no thought to how it will be finished, what the coping will be, how the decks will be arranged or about specific dimensions as they relate to materials. This is completely backwards and grossly inadequate: All such details must be known before a shell is built!

In other words, these firms present “plans” but assume no role in or responsibility for making them work. I can understand this impulse to dodge the hard stuff: After all, it takes a lot of mental energy to develop a comprehensive project vision. But like drawing, visualization is really a skill – and another one that can (and should) be learned and improved with time and experience.

For myself, I am most fully engaged when I sign on to build one of my designs. I know what information my clients will need to see and will generate perspective drawings of key details. These might include step details, material joinery and edge treatments – basically everything it takes to help a layperson visualize the space in real detail. And depending on the clients, this can get intense, right down to the appearance of the grout joints so they’ll know just what they’re buying.

As needed, I also provide sample boards of materials. We’ll talk about the various possibilities and, in general terms, their relative price points – nothing too specific, however, because at this point I haven’t contacted suppliers and don’t have adequate information about quantities, dimensions or applications. In other words, firm pricing is still a fair step down the line.

DESIGN AND BUILD

To this point, we’ve talked about projects that I’ve designed and also will build. That’s almost always my preference, because I hate the idea of my efforts being distorted or downgraded by builders who don’t know what they’re doing.

When I build my own designs, I know I’ll be using the best subcontractors and that the work will be done right. By contrast, when another contractor comes in and takes over the construction end of the job, I have no way of knowing what may or may not happen to the project, although my general suspicion is that the results will not be great.

On those occasions where I’m doing only a design, I provide the details described above along with a plumbing schematic, electrical schematics and equipment lists. If that’s all they want, we shake hands and I’m done. If they want more – structural details, for example – I will take care of providing those as well and whatever else they require by way of documentation, but I do not hang around or offer to supervise the installation by someone else: Odds are I’m going to be frustrated endlessly by scores of little things that are likely going wrong, and I won’t put myself through that ordeal.

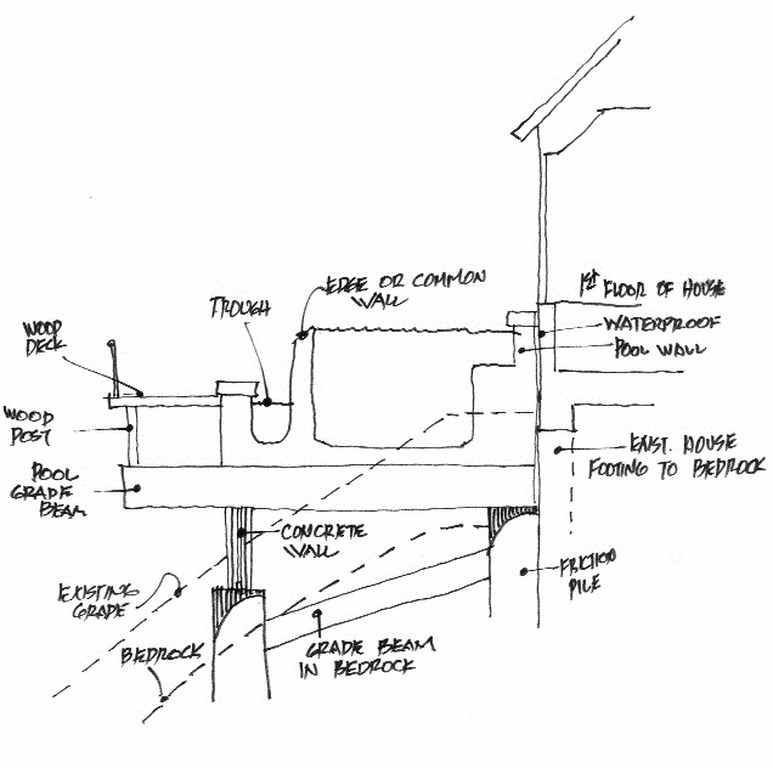

| In developing design ideas and explaining concepts to clients, the fact that I can draw in clear and communicative ways is a huge asset: It lets me work right through any roadblocks to their understanding of what we’re discussing, helps me explain details such as the importance of managing intersections of materials and in general allows me to help them visualize a project’s potential. |

In this context, I don’t ever represent myself as a “design consultant”: I’ll either design the entire project and walk away or, preferably, design the project and see it through to fruition. The subcontractors I work with are incredibly accomplished, so I have complete confidence that when I design something, it can be built (and built well) if my people are involved. By contrast, I just can’t have that same level confidence with people I don’t know.

As an example, my friends John and Luis Marquez at Tony Marquez Pool Plastering (Sun Valley, Calif.) have been with me for nearly 30 years. I know that when I specify a custom plaster color, whether it’s red or green or plum or yellow, they will create samples for my clients and then come through on site with a completely accurate final color. As a designer, knowing their capabilities and reliability gives me a confidence and freedom I’ve never been able to find elsewhere.

This is why I will fly my subcontractors all over the country or even across the globe when the need arises: If that’s what it takes to make certain a design is executed per plan and to everyone’s satisfaction, then that is what I do without a moment’s hesitation.

GOING PRO

As I’ve mentioned many times in these pages, there’s no shortcut in becoming a designer: It takes education, self-discipline and practice – and simply calling yourself one does not mean you are one.

My putting this thought in such blunt terms has upset people through the years, but I’ve never believed that being paid for design work is something that qualifies anyone to assume the title. If that were the case, the hacks who pull templates out of their briefcases would on some level qualify to call themselves designers, and nothing could be farther from the truth.

|

In the Ballpark I’ve often said that you cannot determine the exact price of a project without first knowing what the foundation structure will be based on soils reports and structural engineering. But that is not to say I won’t offer clients general ballpark estimates of what we’re talking about for a given project. Those estimates are always qualified, and I stress the fact that the engineering work might significantly change the numbers. At the same time, I don’t want to be spinning my wheels when I know a project might ultimately cost $500,000 when the client is looking for something for $100,000 or so. Yes, what I offer is guesswork, but these are well-informed generalizations based on nearly 30 years of experience. If I’m working on the New Jersey shore, for example, I know we’ll be building in sand and that everything will most likely have to be set on pilings. If I’m on a hillside in southern California, I know that we’re likely talking about major support structures, typically grade beams and piles. With this extensive background, I’m confident that my ballpark musings won’t be too far off the mark. But there are always surprises – weird soil formations including expansive bedrock and other conditions that can make anyone crazy – so I do all I can to let my clients see and understand the potential for greater costs. As I see it, these general discussions of price are part of the qualification process and a means of avoiding the wrong path. When it comes to anything approaching a firm price, however, I need all the information I can get – soils and geology reports, structural engineering plans, a complete materials list with all quantities indicated and complete construction documents – and even more as the situation warrants. — D.T. |

I have long been amazed at what some self-styled designers try to pass along to homeowners as “professional” design work: Shabby hand or CAD drawings that simply do not deliver what any client who’s ever worked with an architect (as a great many of my clients have) would expect. And padding thin design work with sheet after sheet of standard details doesn’t fill the gap.

Anyone who has studied art history, industrial design, landscape design or the fundamentals of architecture is generally self-aware enough to recognize gaps in what he or she knows, but the real advantage these people have is that they are also aware of what they need to do to address those gaps, where to go to get knowledge or advice or instruction. In that sense, designers are constantly aspiring to reach new levels and figure out innovative ways to use design as a means of creating works of art.

The key to all of this is not being afraid of what you don’t know: The moment you embrace your own shortcomings and start working to advance your knowledge, you are on a straighter path to becoming a true designer. And if you supplement practical experience with a good dose of formal design education, I firmly believe you’ll be surprised by what you can achieve.

Next: The formal presentation of the design to clients.

David Tisherman is the principal in two design/construction firms: David Tisherman’s Visuals of Manhattan Beach, Calif., and Liquid Design of Cherry Hill, N.J. He can be reached at [email protected]. He is also an instructor for Artistic Resources & Training (ART); for information on ART’s classes, visit www.theartofwater.com.