Graceful Reflections

In all my many years of working with water, I’ve never grown tired of its remarkable beauty and complexity – or of the variations it encompasses, the ways it changes and the endless fascination it offers to those who come into its presence.

At the heart of water’s ability to inspire us and rivet our attention is its capacity to reflect. There’s something truly magical about the way water mirrors the sky, a surrounding landscape, nearby architecture or a well-placed work of art. It’s a gift of sorts, a timeless bounty that has captured imaginations ever since Narcissus fell in love with

his own image on a still pool of water.

What’s so amazing about reflections is that, as watershapers, we have the opportunity to wield them in ways that will create constant delight and enjoyment for our clients. Whether it’s a simple pond, an architectural waterfeature or some other body of water, we can deliberately use the play of light on water to great effect. Some truly curious surprises await, however, unless we understand the consequences of setting what is virtually a mirror at our feet.

FROM THE BEGINNING

Using reflection to the greatest effect requires us, I think, to consider it from the outset of a project. In fact, when I visit a site for the first time and begin to feel the inspiration of a design materializing, I quite often focus on how reflections will work as the key feature of the entire composition.

This is no small task, because there are huge differences in the results that may be achieved depending upon the location of the water relative to the main viewing areas and the sun. As a consequence, issues of directionality and points of view become extremely important, as do edge treatments, surrounding landscaping decisions, associated rockwork and/or placements of works of art. There is often a trade-off between the need to use a particular location versus the spot where the best reflection will be achieved.

A great potential awaits that magical moment when a waterfeature is finally filled and takes on its role as mirror – but allow me to mention some of the pitfalls and a few of the mistakes or unintended consequences that commonly occur when reflections are part of the watershaping package.

For myself, I learned early on that reflections are a two-edged sword that can be used wonderfully well – or will amplify design flaws. As an example, I once installed a pond that had a beautiful, curved wooden bridge crossing over part of it. I love the way architectural elements such as bridges are reflected and thought this particular bridge would add beauty to the whole scene.

| Reflections offer extraordinary optical options: One moment the water surface can be viewed as water continuing to the very edge, then, with a blink of the eyes, the image changes to one of an upside down landscape or structure. The situation is such that the water surface seems to expand and contract at will. |

As it turned out, all sorts of conduits and plumbing had been run on the underside of the bridge – a not unreasonable way to conceal such items. When we filled up the pond, however, all of those unsightly colored pipes and lines were vividly reflected on the water’s surface, and we ended up having to encase them all to solve the problem.

That was an easy correction, but finding solutions is more difficult when the problem has to do with a failure to consider the way the edges will be reflected. As already intimated, reflections shine a particularly harsh light on basic mistakes. If, for example, you have rocks at the edges that are not seated below the waterline, you can end up with a reflection of the underside of the rock on the water – a startlingly unnatural look.

As another example, if you have a band of rock or brick at the water’s edge, you can assume that it will appear twice as tall – that is, your well-proportioned, 6-inch band of brickwork will appear as a foot-high wall when reflected and may end up visually overpowering the entire pond. That’s not what we try to achieve in most cases, and the result is shrinkage of the appearance of a body of water that creates what I consider an undesirable, closed-in effect.

In similar fashion, I’ve seen situations in which nearby walls or fences are reflected in the water and inadvertently form massive blocks on the surface, resulting at times in a terribly dominating or unbalanced look. A rim or wall on the far side of a pond that slopes from left to right or right to left is an unnerving site, for example, and should be avoided: It makes the water surface seem tilted.

In other words, there is a premium on considering all structures that surround the water, including those that are at some distance from the water itself.

TO GREAT EFFECT

Avoiding such pitfalls and mistakes is really a simple matter of considering these issues as you plan the work and recognizing that the deliberate use of reflections raises the stakes for many of the design decisions you’re making. That in mind, the question then becomes not only one of how we avoid errors, but also and much more important, how we maximize reflective qualities to create the most beautiful body of water we possibly can in a given setting.

To me, the real work with reflections begins with edge treatments. As I’ve mentioned in past articles, I have a great love of brimming water. To me, water surrounded by steep banks and tall edges tends to look imprisoned, diminished in scale and half empty. This appearance is greatly exaggerated by the reflection, meaning one must remember that anything on the edge will double in size and can make a body of water seem much smaller than it actually is.

By contrast, when we work with water that rises to within an inch or two of the rim, we create the opposite effect, giving the impression that the water is free and unfettered. This brimming water also creates what is effectively a larger reflective surface and encourages our eyes to explore the transitions between the water and the surrounding landscape. We get the further sense that the water is the key to the landscape or garden and perceive a delightful augmentation of the dramatic essence of the space.

| There’s a reflective benefit to size: While stunning images can be mirrored in even the smallest of dark pools, truly large expanses of water enable the reflections to be clearly understood and greatly enhance the drama. In these situations, special effects may be achieved merely through the positioning of one object relative to another. |

This is one of the main reasons, by the way, that I always favor upsizing bodies of water relative to their surroundings. As suggested above, reflections of surrounding trees, architecture or other features at the edge may make the surface of the water look smaller. If the body of water is small at the outset, then a large, featureless object reflected in the water will make the vessel seem diminutive, even forlorn. Just as plants that encroach from the edges reduce the effective surface area, so, too, do reflections.

A quarter-acre pond located a few hundred feet away from a home or other significant viewing position is going to seem quite small and will offer little by way of compelling reflections. In that same setting, however, a half-acre pond will seem triumphant and capture reflections that will command attention.

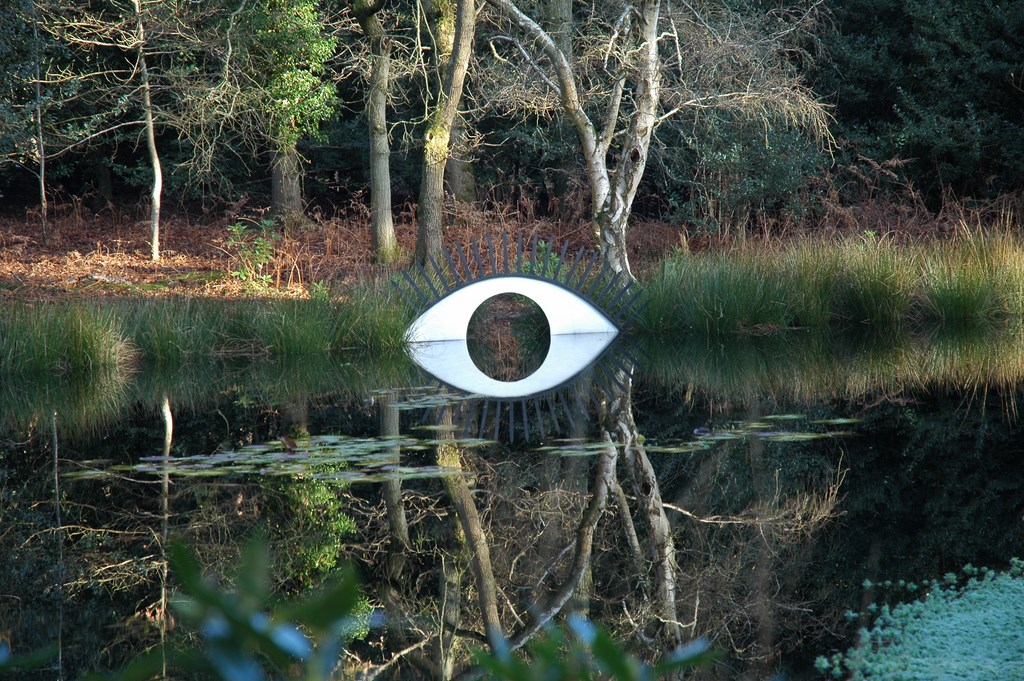

In a situation where the water must be enclosed by some form of raised edge – perhaps a small retaining wall to hold back a slope – then focus on making it attractive by using an interesting natural stone or brick courses or some other decorative treatment. Perhaps one could make the edge a sculptural element and use the reflection to complete a shape or pattern. In one project, for example, I used a reflection to form the bottom half of an eye I’d shaped in stone. It was quite dramatic and surprising.

Reflections and architecture are a particularly great pairing that has stood the test of time. In addition to the Taj Mahal and the reflecting pond on the Mall in Washington, D.C., it has found brilliant applications with modern architecture as well. In all these cases, reflections are used to enhance an already beautiful structure, adding substance and elegance to a scene that could not be achieved in any other way.

PROXIMITY ISSUES

Not quite hidden in this discussion so far is the observation that reflections and their use magnifies the need to pay attention to balance, scale and proportion in designing a comprehensive space. As noted above, designs that seem perfect in all relevant ways can be diminished if you haven’t considered the role reflections will play once the water is introduced.

Another issue concerning reflections that needs to be considered from the start is the simple matter of proximity to the water’s surface of both viewers and the objects being reflected – that is, the basic geometry of the setting.

| A pond thoughtfully positioned will be able to capitalize on the reflection of a nearby house or, as in this case, provide a view toward the unique ‘completion’ of an unusual sculpture. These are bonuses that come with the water’s primary role as focal point and mirror – and this potential must be anticipated in order to design landscape features that conduct people to suitable viewing positions. |

If, for example, you have a raised terrace or deck that hovers over the water’s edge, viewers in that location will be looking almost straight down at the water, and most of the reflection they’ll see will be of the sky – magnificent in its own right but not, perhaps, what you had in mind as a designer.

Conversely, if you put those same viewers on a platform that’s down at the level of the water’s surface and back some distance from the edge, the viewing angle is quite oblique and they’re only going to see the very low features on the opposite side of the water – and the sky will be reflected not at all. Indeed, it is the bank and emergent plants on the other side of the pond that will be reflected.

|

Black Water It has long been apparent that dark, acidic water carries beautiful reflections on its surface – in contrast to the pale, alkaline or chalky water of a white-plaster swimming pool that shows little or nothing by way of reflections. For years now, I’ve enhanced this contrast by using a product from Pylam Products Co. (Garden City, N.Y.) – a wonderful black dye that, in just tiny amounts, turns water a wonderfully sharp, jet black and thus dramatically enhance any reflections perceived on the water’s surface. It is non-toxic, doesn’t hurt fish or aquatic plants and doesn’t seem to stain the surfaces it touches. Of course, if the idea is to see what’s going on beneath the water’s surface, this isn’t the way to go. But if your aim is to create dramatic reflections, there’s absolutely nothing like it. On occasion, I’ve used it in a sleight-of-hand trick that lends a sense of drama to unveiling reflections for my clients: If you add the dye to water in just one place, it will spread slowly across the water, and as this happens, vivid reflected images will appear as though I am unrolling a huge painting. The effect of this momentary astonishment is quite unforgettable, but the lasting effect on the darkened water is a mirror-like perfection that is its own longer-term source of satisfaction. — A.A.W. |

In most cases, it’s not practical or even necessary to alter the lay of the land in service to reflection, but it is important to organize features that can play key roles here, including stands of trees, rock formations or edge treatments that are attractive to viewers on available lines of sight. We must always be mindful of the positions viewers will take, whether they’re inside the house itself or are standing or sitting in some location that’s been set up for relaxation.

By designing pathways and places of repose, we can essentially control where people will go in relation to the water and the angles at which they will see it. It’s these focal points that must be most fully considered: This is where the designer takes control and is given opportunities to surprise or reward those traveling along a path or reaching some destination. Perhaps that final position on a bench overlooking the water will be the only point in the yard from which the ideal intended reflection is seen.

This mandatory viewing point is particularly effective when your intention is to showcase a piece of sculpture or an architectural feature – the classic example being a half-moon bridge that forms a circle in the water only when viewed from a particular position on the shore. When done correctly, the effect is unbelievably dramatic, and I must say that this is an approach I’ve found myself increasingly interested in using. It’s not a new idea by any means: In fact, no matter the era, sculpture and water have always gone together in an almost symbiotic way.

GREAT EXPECTATIONS

Another point is raised by the story of the unsightly conduits under the bridge: On occasion, reflections will reveal something that’s not visible from the point of view of a person standing or sitting by the water.

I recall a situation in which a beautiful weathervane was visible in a reflection in the water even though it was hidden from direct view by a stand of trees on the opposite side of the pond. If you were to lie on your back in the middle of the pond and look up, you could spot the weathervane just under the line of trees, but from an observer’s normal position, it was hidden – and came into view only as its reflection in the water.

Again, this is an effect that can be used to great advantage – or it can be an utter disaster if what’s being reflected isn’t something you want anyone to see.

Of course, it’s unreasonable to think you can anticipate every single possibility along these lines, but the more you consider the viewer’s perspective and the nature of the reflected scenery, the more you’ll be able to control the consequences when the waterfeature is finally filled.

| Dark water forms a brilliantly reflective mirror, and indeed, the best reflections to be had anywhere occur naturally on black, acidic, peaty ponds. On ponds like these – or on man-made expanses in which the water is artificially darkened – the reflections on a still evening can be utterly breathtaking |

In that same vein, we must always be aware that reflections will reveal the undersides of “structures,” whether they are trees, arches, bridges or the eaves of a building. If these forms are attractive, the resulting reflection can be extremely positive; if they’re not, however, the opposite is true and you can find yourself with a reflected visual that in some cases cannot be altered.

Another fascinating piece of the puzzle has to do with the positioning of the body of water relative to both the house and the sun. In the Northern Hemisphere, for example, the north side of any house or building is usually in shadow. If that structure is tall, then a garden beyond will consistently be darkened and in the shade – unless, that is, we use reflections off water to change the situation.

Providentially, if we place an expanse of water to the north of such a building, suddenly all of the sunlight that falls on the trees or landscape on the far side of the pool or pond is reflected in the water. These may easily be reflections from a neighbor’s property that lies beyond the shade – thus giving a new slant to “borrowed” landscape: Now you’ve created a situation in which the sunlit branches are at your very feet and being reflected up into your eyes.

Moreover, all that brilliant light reflecting off the leaves and branches of the trees will bounce up through the windows and into the house, which leads to the observation that one can actually light interior spaces simply through the placement of a body of water. The upshot is that a view that is distant moves much closer and we’ve used the sunlight originating in the south to light an otherwise dark area.

DIRECTIONAL PLAY

This awareness of the sun’s orientation opens a rich cluster of opportunities to be achieved with water and reflections, but there are some cautions to consider.

If the water is located to the south of a building, for example, you’re likely to see pleasing ripples of light reflected onto the ceiling as the sun streams in through the windows. But the sun is shining from behind the water, so the reflections will be poor and confined to the dark silhouettes of whatever objects stand between the pond and the light source. Also, the brilliant sunlight will be reflected directly up into the viewers’ eyes, which is why it’s not unusual in these situations that the homeowner will end up installing shades or other window treatments to reduce the glare.

Although it is rarely my preference to work with water close to the south side of a home or some other major viewing area, I must say that this can actually be an advantage in northern climes: Essentially, you see two suns and the extra light adds warmth on chilly winter days. With that exception, however, it’s rarely advantageous to be looking south across a body of water if what you seek to exploit is reflections.

|

Reflections in Motion As a rule, working with reflections means working with still water. As we all know, however, when you drop a pebble into flat water, the spreading, concentric circles disrupt reflections until the ripples subside – and I, for one, have always loved looking at that effect, as when the first few drops of rain fall to distort reflected images with their spreading, undulating rings. By extension I have used this same effect when working on streams where there might not be much by way of clear reflections because the surface is riddled with the waves, ripples, eddies and currents of water in motion. Despite this diffusion of reflections, it’s still possible to create fascinating views. If you place a stand of trees that have brilliant foliage as a backdrop, for example, the reflection in the moving water will become bands of brilliant light similar to stripes hastily put down with oil paint onto a canvas. You won’t see the forms or textures, but the colors on the moving water can be truly spectacular in their own unique ways. — A.A.W. |

In the main, I prefer working with water either to the west or east of a home or its prime viewing spaces. If it’s to the west, there will be wonderful, cool reflections in the morning, and in the evening trees and landforms on the other side of the water will be revealed in exciting black silhouette with beautiful sunset colors behind them. Many people especially enjoy the sunset and twilight hours, and an expanse of water essentially creates a clearance in which trees or other objects do not block the light. Thus, the fading light bounces off the surface of the water and creates terrific views from a deck or outdoor cooking area.

Conversely, if the water’s to the east of the house, the rich golden evening light will provide spectacular warm reflections of foliage beyond. This effect can be truly spectacular in autumn and winter: When leaves turn colors in the fall, it’s as if the water is on fire with the warmth of reds, oranges, yellows and gold. And in winter, it’s easy to enjoy the terrific potential of colored stems, berries and bark. No matter where you are, as the air grows still toward dusk, there will be stunning images lingering on the mirror the water provides.

For this reason, it’s particularly important to be aware of colors in the landscape and the textures and forms of trunks and stems. Those issues are always important, of course, but with water to the east, you can never forget that the selections you’re making will be part of an amazing late-afternoon/early-evening spectacle.

In many situations, naturally, you’ll have no choice about where the water is located relative to the house, but it’s important to be aware of the effects of directionality and plan accordingly. It’s also useful to discuss these issues with clients as the work is being planned: After all, they need to understand how reflected sunlight will play into their daily lives.

IN THE EYES

When people ask me about reflections and how best to wield their mesmerizing power, I always say that the key is to consider them much more fully than one might initially think would be necessary. In a very true sense, reflection is at the very core of why being near water is so fantastic. This is why we, as designers, need to consider what we want to see – and recognize just as fully what we don’t want to see. Either way, the importance of reflections cannot be overstated.

| Once you begin thinking about reflections in a deliberate way, all sorts of opportunities present themselves. Take the case of monotonous masonry, which might have a restrictive effect on water sited close to architecture (left): In this case, a spout producing small ripples or perhaps some sculptural additions to a wall will alleviate this. In other cases, you might have the inspiration to add some organic object or a structure (middle left and right) – and sometimes you might be just plain lucky and find that nature has created a piece of sculpture for you (right). Such bounties can be exalted by providing a special viewing point for their enjoyment. |

Through thoughtful use of reflections, we have the ability to create aesthetic bonuses with water that simply cannot be achieved in any other way. Yes, there will be situations in which the reflective quality of the water is not the focal point, including cases where the “underwater landscape” is the star feature ( a wonderful topic for future discussion), but even in those cases, when viewers stand back from the water’s edge, reflections very likely will come into play.

This leads to one final point: Whether you think about what you’re doing or not, working with water inevitably means working with its reflective qualities. You don’t really have a choice, as it’s a matter of optical physics. So the question is, do you leave it to chance or consider its effects so that your watershapes embrace their full potential?

For me, there’s nothing quite like the feeling I get when I see reflections in water I’ve shaped for the very first time: It’s as if a curtain has been pulled back and a spectacular scene that’s never been witnessed before is unveiled. As long as my eyes are working, the thrill of seeing such reflections will never cease to bring me great joy.

Anthony Archer Wills is a landscape artist, master watergardener and author based in Copake Falls, N.Y. Growing up close to a lake on his parents’ farm in southern England, he was raised with a deep appreciation for water and nature – a respect he developed further at Summerfield’s School, a campus abundant in springs, streams and ponds. He began his own aquatic nursery and pond-construction business in the early 1960s,work that resulted in the development of new approaches to the construction of ponds and streams using concrete and flexible liners. The Agricultural Training Board and British Association of Landscape Industries subsequently invited him to train landscape companies in techniques that are now included in textbooks and used throughout the world. Archer Wills tackles projects around the world and has taught regularly at Chelsea Physic Garden, Inchbald School of Design, Plumpton College and Kew Gardens. He has also lectured at the New York Botanical Garden and at the universities of Miami, Cambridge, York and Durham as well as for the Association of Professional Landscape Designers and the Philosophical Society.