National Wonders

By now, the thought that watershape and landscape designers need to study nature if they want to replicate it in their projects is basically a cliché. Truly, if you want to mimic nature successfully, you must first know it intimately.

What many miss in all this, I believe, is a deeper level of “knowing” that goes well beyond simply observing nature as a source of techniques and ideas. Frankly, I think that as designers and as human beings, we are much better off when we also learn how to become nature – by which I mean letting the sights, sounds and smells draw us physically into the place.

In doing so, we engage in experiences so profound that the mere mentioning of that place will set us off with memories we will share enthusiastically – or can use as parts of our latest projects.

No matter how often I visit natural places, I’m always amazed at the interactions that take place among the basic elements of water, stone, soil, plants, sunlight and wind. I know I will never be able to comprehend all of the complexities and nuances that have gone into shaping what I’m seeing, but by witnessing these places and reveling in these experiences, I come away with a greater, more intuitive understanding of the dynamics of the natural world and have, I trust, better prepared myself to approximate its features in my own work.

In my case, I seek these experiences with regular visits to national parks. It’s easy where I live in the western United States: Some of the most spectacular environments on the planet are being preserved here within easy driving distance. For years, I’ve seen these places as being among the most valuable assets we designers have – an awesome embarrassment of riches for anyone who values the natural world.

In this pictorial feature, I’ll demonstrate what I mean by sharing my perspectives on just four of these magnificent places: Yosemite, Zion, Bryce Canyon and the Grand Canyon. Each in its own way, these parks offer any visitor treasure troves of beauty and inspiration. And for those of us who are also designers, they offer invaluable lessons in the ways water sculpts the land.

Yosemite

Established in 1890, Yosemite National Park covers more than 700,000 acres – about 1,000 square miles – in the mountains of east-central California. Famous for its biodiversity, trees, geology, abundant waterfalls and crystalline streams, its beauty has inspired artists for generations.

I’ve visited Yosemite regularly for more than 30 years now, starting when I first moved to California. Nowadays, I go there at least once a year, encouraged by the fact that there’s always much more to see. Indeed, it’s one of those places you could visit monthly (or even weekly) and still never grow tired of it.

Yosemite was formed by a glacier in the last Ice Age. It consists mainly of a massive U-shaped valley with cliffs soaring above forested slopes and the valley floor. When you first reach the core of the park, you’re stunned by its sheer grandeur, even if you’ve prepared yourself by looking at photographs: You simply can’t anticipate the scale and drama of the place until you see it firsthand. (The same is true of all four of these parks, so I’ll make this point here once and for all.)

Everywhere you look, the scenery is defined by the presence of water. One of my all-time favorite Yosemite hikes is the Mist Trail, which follows the water pathway leading to the Vernal and Nevada falls. All along this trail, you see evidence of water’s work: boulders cleaved by ice; gravel tumbled into shape by spring runoff; tree roots exposed by brisk flows; and fallen trees that have changed the course of the river. There are also small alcoves with moss growing on the granite roof from which small, perfect droplets of water that has traveled through the rock for years finally form and drip – a process I reproduced on a boulder in a teahouse project of mine.

The specific “lessons” to be taken away from a single hike of that sort could become an article many times the length of this discussion. Indeed, an examination of the forces of erosion alone would do that: how the water naturally breaks down the landscape, exposes parts of subsurface formations, creates various types of cascades, waterfalls, pools and streams and weaves together an infinite tapestry of sight and sound. If you also consider the juxtaposition of materials, colors and textures, the experience can readily be translated into designs of all types – not just the naturalistic ones.

I’ve been here when there were roaring torrents at every turn and then returned months later to find dry streambeds. Both extremes are useful: You can witness the aesthetic variations created simply by the volume and velocity of moving water – or you can study the stone structures that water creates and feel its presence even when it’s not there.

Most visitors to the park are satisfied to be blown away by views from a distance, but I recommend getting right up close to examine the interactions of stone and plants, stone and water, water and plants and, occasionally, of all of them with the animals that live in the park. If there’s any space on the planet that holds up under that sort of close scrutiny, it’s Yosemite – quite simply one of the most spectacular places I’ve ever seen.

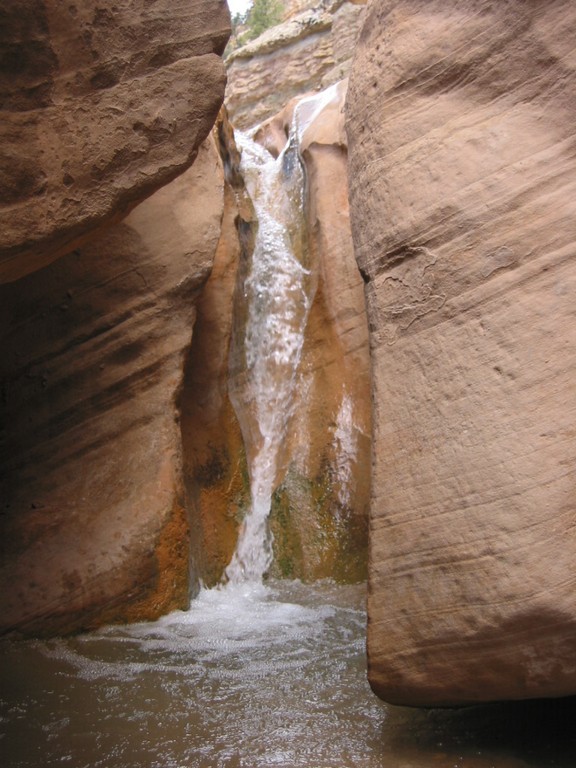

Zion

Set in southeastern Utah on the northeastern edge of the vast Mojave Desert, Zion National Park was established in 1909 largely to preserve the homeland of the Anasazi tribe of Native Americans. It’s a relatively small national park at just 229 square miles, but that’s enough to encompass Zion Canyon and the north fork of the Virgin River.

In terms of its influence on the art of watershape and landscape design, Zion may well be one of most dramatic examples of unfolding surprises that you’ll ever see. To get there, you drive across seemingly interminable miles of flat grassland – a barren wasteland that is the antithesis of beautiful and remarkable. You then enter the park through an impressively long tunnel, emerging into the midst of an oasis defined by huge rock formations, evergreens, ferns and scores of different flowering plants.

What Zion lacks in scale or pure grandeur, it makes up for with endless subtlety and constant revelation. As is the case with Yosemite, Zion is a complex study in stone, plants and water, but it draws added significance from a fascinating layering of visual features. In particular, Zion includes some of the most interesting erosion patterns I’ve ever seen anywhere.

One of the easiest hikes in the park leads you to a place known as Fern Grotto, which is completely hidden until you walk into it. This beautiful space includes sheer cliff faces through which water seeps to create a spectacular pond. As the name implies, the entire scene is defined by thick ferns that drape across the rocks as a natural hanging garden. When sunlight filters through the ferns, you experience visual explosions in vibrant, deeply soothing green.

The entire park is a treat, but this one enclave is a perfect example of how your emotions and perception of a greater space around you can be instantly transformed by entering a compact, comprehensible space where the sights and sounds of water and plants infuse the landscape with intensity, volume, scope and life. And there’s much more, because Zion offers other surprises spaces at almost every turn

Bryce Canyon

Bryce Canyon National Park is another treasure of southwestern Utah, and although it’s just 50 miles from Zion, it might as well be on a different planet. Established in 1924, the park covers just the 56 square miles atop the Paunsaugant Plateau – and the star of the show is a sloping semi-circle defined by hoodoos, one of the most unusual rock formations found anywhere in the world.

With respect to direct design lessons to be learned in national parks, Bryce Canyon offers the least of any of the four parks covered by this discussion. In my estimation, however, it’s just as worthy of a visit as the other three simply because it is so strange – and so uniquely beautiful.

Rising to 9,000 feet at its summit, the area is sparse in plant material beyond a few pine groves, and there isn’t much open water to speak of. Instead, the key to Bryce Canyon is geology and the hoodoo formations carved there by water, wind and ice. Indeed, when you visit the park and catch a glimpse of the hoodoos for the first time, you feel as though you’ve stumbled upon a completely different world filled with towering rock spires and ridges that look like something an avant garde sculptor might create.

Beyond these fantastic, dominating forms, the careful observer begins to pick up on the colors of the stone: Layers of bold orange, bright yellow and brilliant white provide some of the most surprising vistas I’ve ever seen and have inspired me more than once to be more daring in working with colors in some of my designs.

As you hike through this landscape, your sense of being on an alien planet only intensifies. Some of the hoodoos reach heights of 200 feet, and their scale makes them both awe-inspiring and a bit eerie at times. And the amazing thing is that these formations were not carved by rivers or glaciers but were instead shaped by the steady sculpting power of rain, snow and wind.

In practical terms, visits here may be most rewarding to modern artists, simply because the forms are so dramatic and unusual. Speaking for myself as a watershape and landscape designer, however, I’m satisfied by the fact that the place is just incredibly cool.

The Grand Canyon

Last but certainly not least in this tour is Grand Canyon National Park. Established in northwest Arizona in 1908, the park covers an area of more than 1,900 square miles while stretching across 277 miles in length and reaching down a mile at its greatest depth.

As with Yosemite, the Grand Canyon owes its entire existence to water and stands among the world’s most dramatic example of the power of water to carve the land. Words simply aren’t adequate to describe its natural majesty: It is, in short, an undisputed wonder of the natural world.

There are basically three ways to experience the Grand Canyon: up on the rim, on the walls or down on the Colorado River. I’ve done all three and prize the fact that each experience is totally different.

There are basically three ways to experience the Grand Canyon: up on the rim, on the walls or down on the Colorado River. I’ve done all three and prize the fact that each experience is totally different.

For anyone involved in using water in their designs, I see the Grand Canyon as an absolutely essential destination – but I say the same to non-designers as well. If you have any interest at all in geology or natural science, the canyon is an open book ripe for study and ready to see and touch. And at the bottom of the canyon are exposed rocks that are among the oldest on the globe, dating back some four billion years to the Earth’s infancy.

In every sense, the Grand Canyon is a study in extremes. On one of my trips, for example, it was snowing at the rim, which stood at a 7,000 foot elevation. I hiked down the canyon walls, and by the time I reached the base it was time for shorts and swimming before boarding the boat – a brisk, one-day experience of both alpine and desert climates.

| Knowing Destinations

In my visits to the four parks under discussion in the accompanying text (and countless others), the idea I’ve had most profoundly reinforced is that human beings are fundamentally at their happiest when they participate with nature. By extension, when we as watershapers and landscape designers set a scene small or large, we are creating places where people get involved with their surroundings – and that’s true whether the scene is the most naturalistic or most architectural. We are in the business of creating spaces where people experience life: where they rest, where they exercise, where they break bread with friends and family, where they grow, where they grieve, where they pray, where they socialize, where they formulate ideas about their future and where they sometimes make love and maybe even die. We create venues of human experience, and that’s a huge responsibility. This is why we should all visit our national parks, because in these places, we see the most dramatic examples of “place” to be found anywhere and are also occasionally in position to see how other human beings respond to and interact with them. Atop and maybe beyond all that high-mindedness, there’s also the fact that exploring these parks is just plain fun. To me, these are absolutely the best places to vacation with loved ones and share experiences with them you’ll all remember for the rest of your lives. These are, in short, wonderful places to rejuvenate your body, mind and spirit. And if you come home with an idea or two that will come in handy the next time you sit down to design a space where people will spend part of their lives, well, so much the better! R.D. |

One of my favorite all-time Grand Canyon hikes led me all the way up to rim, where I saw a tiny rivulets of water emerging from a massive rock formation. I followed along as this tiny flow coalesced and combined with other, unseen flows. As I worked my way down, I observed this force of nature cutting its path through the rock, creating deeper and wider slot canyons, showing where, through the ages, time and water have carved some of their most sensuous and spectacular forms. And the light through these canyons is just awe-inspiring!

In exploring all of this, I was utterly amazed by the thought that, sources unseen, all of this water gathered into larger and larger flows until it reached a point where the trickles had amassed into a 25-foot-wide torrent pushing over a massive waterfall.

It’s a place where you can see the most delicate flowering plants emerge from seemingly impenetrable rock faces; where you can relax and soak in the vast beauty or fully test your physical limits; or where you can experience nature on the grandest scale imaginable or study the tiniest aspects of a spectrum of ecosystems. You can absorb the grace of the most delicate tendrils of water and plant material – or dive from ancient rock formations into the bone-chilling waters of the river.

Again, the value of such visits and experiences isn’t always in the design ideas you might take away from the park; rather, it’s about what you can absorb of the spirit and essence of the places in seeing them with your own eyes and feeling the effects of these experiences to the core of your being. If absolutely nothing else, you’ll walk away with a dramatically amplified appreciation of nature, its sublime delicacy and its raw power.

Rick Driemeyer is founder and president of Both Sides of the Door, a watershape and landscape design/build firm based in Oakland, Calif. His design career began in Ann Arbor, Mich., in the early 1970s, when he became a specialist in interior landscapes and watershapes. After moving to California and expanding his work to include exteriors, he established his current company in 1981, deriving its unusual name from the fact that he now works with both interior and exterior spaces. An Arizona native, Driemeyer traveled extensively as a child with his family and has lived in Florida and Pennsylvania as well as Michigan. He credits this exposure to different types of landscapes and his parents’ love of the arts and nature as primary design influences.