Making Headway

What happens when you take a large group of landscape architecture students and, for a solid week, rigorously school them in the fundamentals of watershaping? You might be surprised: Even though that seems like a short span, my charges took to watershaping like fish to water when I introduced them to the subject this past spring – and the results were both remarkable and inspiring.

As their instructor, I witnessed not only their keen interest but also saw ample evidence that they were applying highly refined design processes and quality design productions in their watershape-related coursework. So despite what some skeptics have been telling me for years, you actually can

teach landscape architects to design watershapes accurately and effectively.

When I began my contributions to “Currents” last year, I led off with a discussion of how ignorance of watershaping on the part of otherwise well-educated designers had created a self-perpetuating information vacuum in our school system. In summarizing my ongoing efforts to challenge that status quo, I reported on the progress I was making with the landscape architecture department at California State Polytechnic University in Pomona, which had allowed me to take a group of university students from all class levels (including some candidates for master’s degrees) through what amounted to a watershaping boot camp.

This “Water Module,” as we’ve come to call it, was intended from the start to bring students’ level of knowledge of watershaping up to par with what they were learning about, say, planting or irrigation. As it has unfolded, I have become more resolute than ever in my belief that this mission of educating landscape architects about water while they’re in college carries a potential for future development that’s far greater than most of the grownups in our industry would care (or dare) to believe.

BIG IDEAS

I’m constantly reminded through my efforts that students desperately want watershaping knowledge but have nowhere to get it unless they happen to be enrolled at Cal Poly Pomona.

I’ve found that when I give them just a bit of information, they clamor for more – something I’ve never, ever witnessed while teaching them drainage or soil erosion. And that makes sense, because watershaping is a romantic pursuit that carries excitement and opportunities to make amazingly positive impressions on clients and anyone else who might come in contact with the output. That’s strongly appealing to young people who have not yet fallen into the well of mediocrity.

And it’s become crystal clear to me that, given the right tools, students learn very quickly and quite effectively.

It has gone so well that my current dream is to take the Water Module on the road and travel from university to university like a latter-day Johnny Appleseed, awakening more of those young minds to the world of watershaping. This traveling “School of Water Architecture” wouldn’t teach anyone how to build a better pool: Instead, it’s about giving students the tools and thought processes they need to be better designers who can turn buildable ideas over to contractors in place of the all-too-typical, meaningless blue squiggles that haunt so many plans.

|

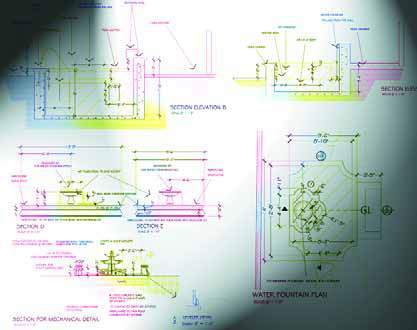

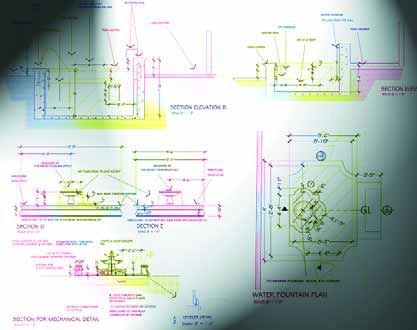

Many of the plans I receive even from professionals lack the level of information and detail needed to bid and built projects, so one of my focuses in the classroom is making certain students understand just how far they need to go to be certain they’ll get the results they’re after. (Drawings by Andrew Witschonke; schematic at the head of the column by Meliana Susanto) |

In other words, I’m after an idealized world in which designers actually design complete systems and builders are allowed to build instead of being left to improvise and compromise. The only ones who might be threatened in such an environment are those who thrive by taking advantage of the current lack of thoroughness in designers’ plans.

Cal Poly has been gracious in allowing me to develop this prototype water-architecture program, and I hope news of the success we’ve had in Pomona starts reaching into other landscape architecture departments across the nation. All I can say at this point is that my students have consistently exceeded my expectations in applying what they’ve learned even in this brief module, and I’m deeply gratified knowing that many of these students will carry this experience with them for the rest of their careers and will doubtless improve on the base of information they’ve gained.

It only takes a small dose of truth to spur inquiring minds to want to know more. I am sure that most of my students can now recognize watershaping for what it really is and will use what they’ve learned to their professional benefit.

The level of class success last spring was best revealed several weeks after the water module was over as I saw the way the information kept feeding back into my regular class of junior-level students. As part of a larger project, I had them design a simple residential pool – and the results simply blew me away.

THE PAYOFF

This class was a mix of students, some of whom had participated in the Water Module, some who had not. The students who had attended the module produced design plans of greater quality than many of those generated by licensed professionals who submit them to my own firm, Holdenwater in Fullerton, Calif., for review and revision.

One student even managed to devise a perimeter-overflow design that was remarkably close to workable – a level of skill that often eludes experienced pool builders and is certainly beyond the reach of most landscape architects.

As I have stated many times before, you cannot bid, obtain permits for or build from most landscape architects’ watershape plans. Though the design concepts may be sound and even outstanding, they come with little or no graphical/textual support. How different would things be if that situation turned around and we were an industry filled with designers who came up with good water-based ideas that came with documentation that made them buildable?

That’s a mind-boggling notion, to say the least – and wouldn’t it create an environment in which designers could command higher fees for their plans and construction processes would be more streamlined, efficient and cost-effective?

If the answer to that question is yes (which is, I believe, correct beyond doubt), then the financial implications alone should be enough to drive this evolution through its next phases.

Look at it this way: With our deflating economy and real-estate development approaching stagnation, it’s time for all of us to expand our horizons. For landscape architects, that means raising our skill levels, becoming more competitive in areas that really matter and charging more for our work – and one big way to do so is to tackle the water part of every job.

For builders (and I’m one of those, too), it means elevating technical skills, learning to do the hard stuff proficiently and opening ourselves to working with designers who generate more elaborate, more comprehensive watershape designs: These projects typically have higher profit margins, and everything becomes optimized when a project moves forward with less guesswork and better sets of plans.

UNCLOUDED THINKING

So what happened in this Water Module? What did it cover? As mentioned previously, parts of the class had to do with history and art history, hydraulics, engineering, conceptual design, materials, construction, industry structure and costs – a starting place that gave the class the background information and tools they needed to design their own watershapes in the final class project.

Along the way, I pointed them to manufacturers’ websites, helping them see what products/services were appropriate for water applications and how to initiate the specification process. That seems basic, but this was essential “stuff” for a group that basically didn’t know where to begin with water beyond swimming in it or drinking it.

I also ran the class through slideshows, lectures, laboratory sessions, a field trip, project work and, finally, a test. Within the module itself, their final project had to do with a water-themed resort property for which there was no stated budget.

In addition to a conceptual design, I expected them to figure out how the watershape worked and how best to communicate it graphically. I also added that the design had to be revolutionary and provocative or I would, as the client, immediately reject it. By that point, it basically went without saying (although I did bring it up) that I did not want to see any three-tiered fountains or kidney-shaped pools!

To spur them along, we took a field trip to an aquatic facility that includes competition pools, waterslides and a lazy river. While there, we visited a state-of-the-art equipment room – a bit mind-bending for students who’d never seen anything more than backyard equipment sets and an experience that let them know there were few practical or technical limits to what they might do.

I knew it was all working when one of them asked, “How do you backwash these large horizontal sand filters?” and another asked, “How much horsepower does this lazy river need to flow right?” That was deep stuff for a bunch of students who’ve never been expected to learn anything more than how to ask a contractor to figure things out for them.

The resulting designs covered an incredibly wide creative spectrum, with at least a dozen highly creative concepts and a couple that struck me as visionary.

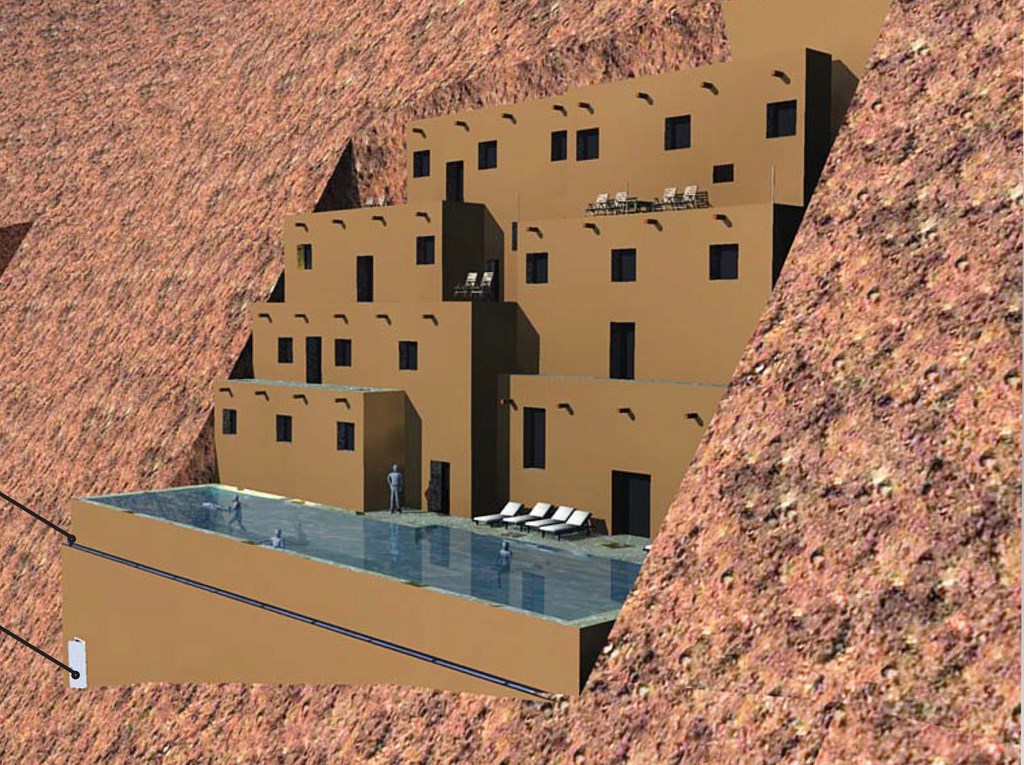

One of the most creative came from a design team that took inspiration from the Hopi Indians. Devising a spa resort on a reservation in Monument Valley, they captured the spiritual importance of water to the Hopi by drawing up cliffside dwelling suites and Hopi-inspired spas that defined connections between ancient and modern times – and along the way addressed myriad technical issues as well.

And that was just the start.

HIGH-FLYING

Just thinking back on these projects yields a proud, awestruck smile.

Another project was based on an appreciation of the pre-Columbian Maya, Aztec, Olmec and Chichimeca cultures. The team’s aquatic facility design used cenotes – the sinkholes found in the Yucatan peninsula – as their point of departure. These huge holes fill seasonally with fresh water and sometimes connect to form underground rivers. This team of water architects used that phenomenon as a springboard for developing a resort with a subterranean lazy river system accessed via naturalistically rendered cenotes that would serve not only for recreation but also as a means of transportation throughout the resort’s extensive, park-like grounds – truly ingenious!

| Translating ideas into technically sound design plans is a skill these students seem to latch onto with relative ease, and the outcome for them as professionals will be a far greater level of control over their projects – right down to getting the materials and equipment they’ve selected used in the construction process. (Illustration at left by Lee Krusa and David Fowler; images at middle left and right by Vladimir Berunza, Gabriel Gitierrez and Celio Ruvalcaba; illustration at middle right by Pavel Petrov and Ben Tamuno-Koko) |

Other projects took a more urban approach, including the one in which a water nightclub floated atop a high-rise building and another that featured a large wave pool. Then there was the one that dealt with the way our five senses interact with water in the confines of a Zen therapy/education facility.

All in all, these students took a defined set of process-oriented design principals and focused them on water – and what they came up with were amazingly creative ideas they were able to translate into technically sound design plans. Isn’t this the way the design side of watershaping really should be?

At a time when it’s easy to get discouraged by the way things are going in the economy, I can’t help thinking that breaking away from convention and mediocrity offers a forward-leading path and that educating a new generation of water architects is the key.

When I look at the output of the unclouded minds of students and see what they can do armed with only a basic information framework, I am hopeful about the future of watershaping. Indeed, if we can get this done and come to a day when watershaping is a standard module in every landscape architecture and architecture program in the country, then it is clear to me that the very best our industry will ever produce is still to come.

Mark Holden is a landscape architect, pool contractor and teacher who owns and operates Holdenwater, a design/build/consulting firm based in Fullerton, Calif., and is founder of Artistic Resources & Training, a school for watershape designers and builders. He may be reached via e-mail at [email protected].