Glass Works

All artists and designers have to come from somewhere, creatively speaking. In our case, we came to watershaping via the world of glass arts and crafts, a starting place that led us first to create unusual sculptures in glass and light – and then to carry our work out into landscapes and especially into settings that feature water.

In collaborating mostly with architects and landscape architects and designers, we at SWON Design in Montreal have found what we believe to be an incredibly rich vein of aesthetic potential. Indeed, we have come through the years to recognize with greater and greater profundity that water and glass are a natural pairing: What light does with water and what light does with glass are similar in many ways.

To be sure, all of us at the firm appreciate other materials. These include stone, for example, which can be used beautifully, elegantly and artistically but is, in our view, ultimately a static medium. By combining glass, water and light, we’ve found a more dynamic niche that enables us to create wonderfully original and endlessly intriguing combinations of visual effects that range from the subtle to the startling.

NEON ON STEROIDS

We started a firm called Skunkworks in 1991 and focused, exclusively at first, on neon art. We set out to break the rules of artistic conformity by creating exterior installations well outside the traditional gallery and formal-arts settings in a form of “guerrilla art”: We set up exhibits in all sorts of places, from staircases and abandoned buildings to architectural façades and even cemeteries.

The bent, twisted and arcing pieces of neon-filled tubing that made up these early installations were meant to stand for no more than 24 hours. We’d invite the public and managed to kick up quite a stir among those who took the time to show up. Looking back, it was all terrific fun, and we ultimately managed to capture a good share of attention in the media and within the more traditional arts community.

What we did grew out of our near-compulsion to use large architectural environments as canvasses for our hand-blown neon-lighting installations in riots of form, color and light.

| We started as renegade neon artists, setting up displays meant for 24-hour exposure in unusual environments – such as, in the case seen here, in a cemetery. |

Steadily expanding our capacity to confront conventional expectations, we began doing permanent neon-lighting installations in a variety of commercial and public settings in North America and Europe. In the background, however, we were experimenting and looking for new applications that involved neon and sculpted glass.

This process led us to increasing involvement with architects, landscape architects and designers: As we began working in a greater variety of settings, we started seeing almost limitless creative potential for glass in the landscape, especially when the setting involved water.

In 2001, we reformed our business and adopted its current name, and we’ve now expanded our repertoire to include work with cast, blown and flat glass. With this expanded palette, we’re bringing a fuller measure of the excitement and vibrancy of glass art to each and every one of our projects.

In designing our pieces, we rely heavily on organic shapes and textures. Our aim is compositions that complement both natural and architectural environments, and we’ve found that combinations of glass, water and light are remarkably adaptable to that mission. Glass in particular has both formal and informal qualities, depending on how you work with it and particularly on how you establish its relationship with other elements in a setting.

FINDING A WAY

Our work is highly “experimental,” meaning we engage in a tremendous amount of trial and error as part of the developmental process.

We have studied art history as well as natural forms, and by now the registry of creative influences we bring to bear is quite vast. We’ve also kept pace on the technical side: In working with glass, it’s crucial to have a firm understanding of materials science and to be able to accommodate its physical characteristics. So while we hang things out over the conceptual edge, we do so with careful planning that takes into account such factors as structural loads and stresses.

|

Boon Companion The vast majority of our raw material is purchased through a New Zealander who lives in Corning, N.Y. Louis Olsen is a brilliant chemist, engineer and glass blower, and we’ve never met anyone as knowledgeable as he is about glass and the gas and electric furnaces used to melt it. Olsen has been instrumental in our work almost from the beginning. In fact, he designed and built the electric furnace we now use. (We chose electric power because it’s more efficient than gas and is more precise.) Our furnace holds about 500 pounds of glass in a crucible inside the furnace body. Depending upon the application, we can heat the material to between 1,800 and 2,500 degrees Fahrenheit. — M.B. & A.B. |

In these areas, the community of experts is a fabulous resource. We work in collaboration with other glass artists and engineers and all share technical information about techniques and the characteristics of different materials that basically keeps all of us out of trouble.

Even in a creative environment filled with experimentation, however, we follow a pattern in the way we do things. Our design process, for instance, starts with the environment in which the installation will be placed, basically because we’re convinced that the setting dictates almost everything.

Whether we’re working with watershapers or landscape architects or directly with clients, we engage in extensive discussions about their desires. We generate piles of preliminary drawings to home in on the basics of the design until everything is clear. We take great pains at this stage for an obvious reason: Glasswork is so precise and painstaking that it’s very difficult to change directions midstream, so we work very hard to be sure that all the principal players in a given project are on the same page before we begin fabricating anything.

Once the direction is set, we start generating glass samples and play with colors, textures and shapes. We pass these samples to clients so they can follow along and see how materials will relate to the environment. Once that stage is complete, the production process begins and all components are assembled.

We generally do our own installations, because we’re quite picky about how our sculptures are set up in the field. And if we don’t do the installation ourselves for some reason or other, we’ll always have one of our designers on hand to supervise every step of the installation.

PROGRESSIVE VISION

To date, the response to our work has been decidedly encouraging, and we’ve been emboldened by this acceptance to expose our work to a broader audience.

In doing so, however, we’ve run into a problem familiar to those who try to break new ground: It’s difficult for others to envision the full spectrum of aesthetic effects that can be achieved using these combinations of glass, water and light. So what we see as limitless, others still view in conventional terms and have a hard time stepping beyond what they know and into the experimental realm we’ve been exploring.

For all that, we’re confident that as more people see what we and other glass artists are doing, acceptance will grow alongside a willingness to step outside the box. And as we’ve seen, the area for exploration beyond the bounds of convention is vast indeed.

Fluid Applications

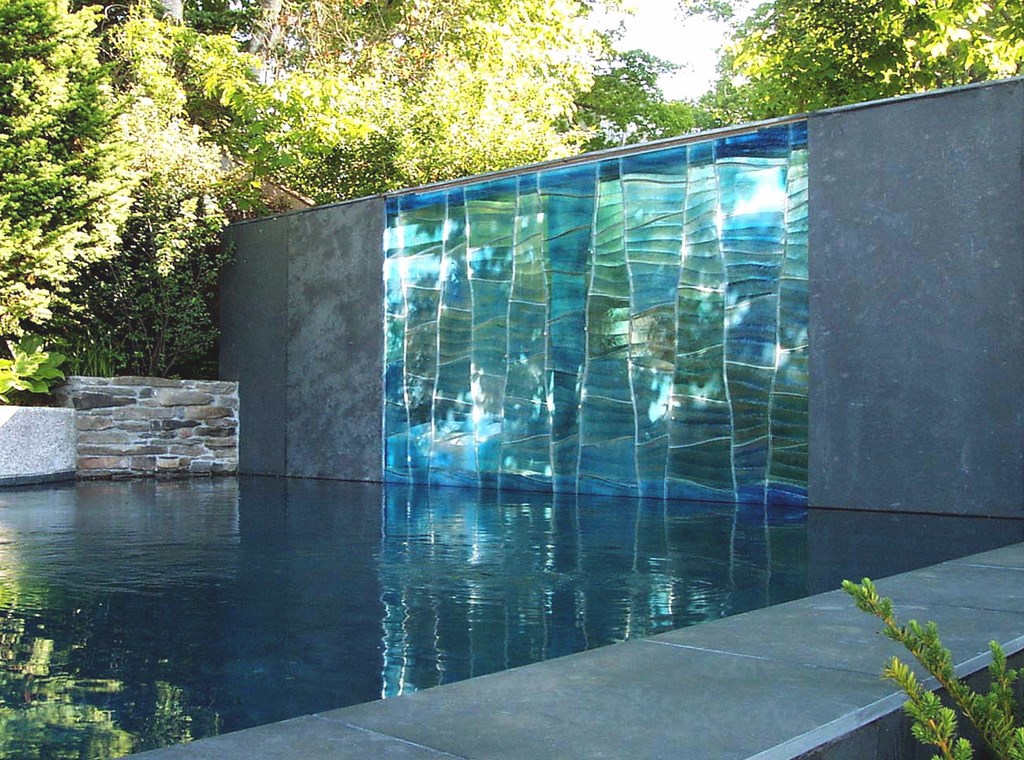

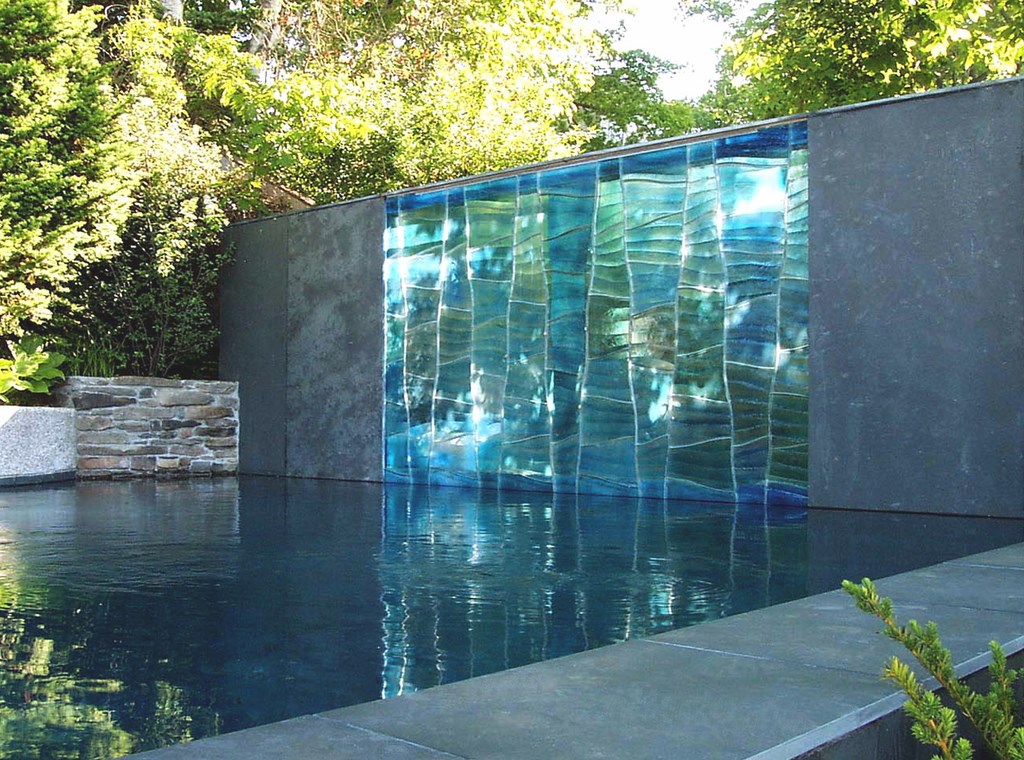

It was a beautiful swimming pool design, with slate-gray materials, a vanishing edge and a beautiful architectural design – and it’s also where our work with water officially began.

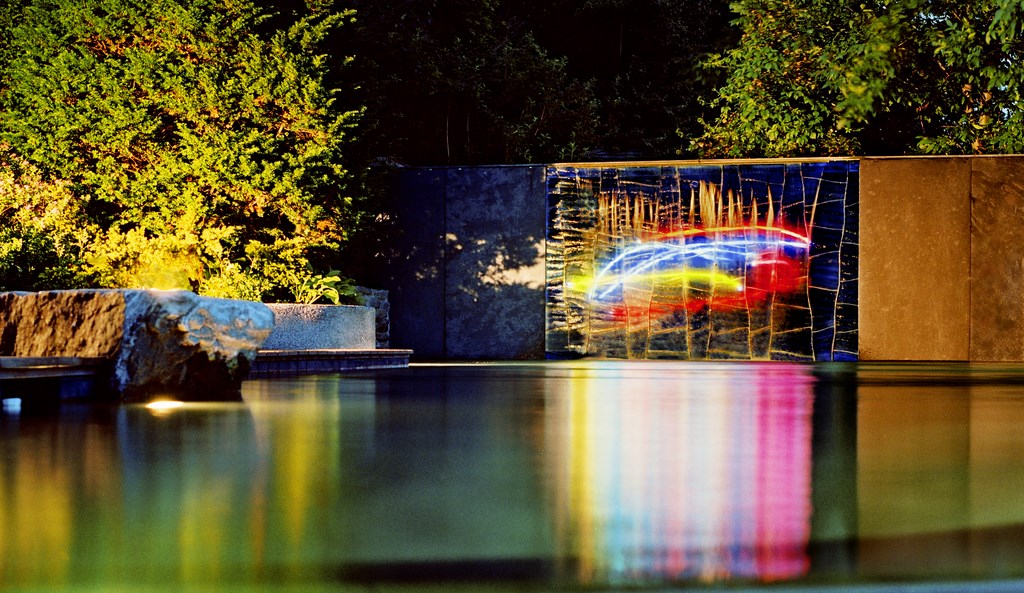

Our piece consists of a large, freestanding wall with an inset glass-block panel. There’s a weir that sends a sheet of water over the glass portion of the wall, but what we did was set things up in such a way that it looks as though water is flowing even when the water is turned off.

The tessellated, differently shaped blocks include aquamarine, greens and blues, but each of the 77 units in the wall has its own hue and color density. Much of the light that penetrates and reflects back through the glass distorts and reinterprets the views of trees and landscape – especially early in the morning, when there’s an interplay of light and glass and surroundings that is truly surprising and exciting. As the day goes on, the wall takes on a different appearance until, in early evening, it reflects warm colors and takes on almost-pink colors. And when the fiberoptic lights are turned on, the composition takes on an entirely different quality.

We drew inspiration for the tessellation from the mind-bending works of Swiss graphic artist M.C. Escher, who used the technique extensively in his mesmerizing designs, but we’re also thinking of quiltmakers and Moorish architecture in creating a wall that stays away from conventional, repeated squares and creates truly dynamic visual patterns – even within individual blocks.

The work is durable, too. This project is set near Lake Ontario and has been subjected to radical swings in temperature with no signs of cracking or damage of any kind. While many people think of glass as a fragile, breakable material, it is in fact remarkably tough when used on this scale.

Glass Hills

In this project, the design was determined entirely by the setting on a 28th-floor penthouse terrace in Toronto. The space was very long but narrow; the client wanted something sleek and modern that could be enjoyed both day and night.

The composition started with five-by-five-foot sheets of half-inch plate glass. We designed what we referred to as “contoured rocks” from those sheets, using forms based largely upon rocks used in Japanese gardens. The panels were cut into these organic shapes and then set upright, with 3/4-inch gaps between them, in a channeled metal frame buried under river rock and glass stones.

The piece consists of three “rocky” masses and measures 14 feet long by four feet wide. The individual glass panels were contoured in subtle, seductively flowing shapes, and a shallow sheet of water covers the base to create reflections and the impression that the massed forms are islands. All the fiberoptic lighting comes from underneath the glass, giving everything a soft glow.

It’s amazing how much the appearance of this piece changes in the course of a day, sometimes in ways we didn’t anticipate. We didn’t know, for example, that some mornings condensation would form on the glass and give it an unusually, opaque quality – and were more than pleased that the resulting effect was so beautiful.

Diamond Light

This project, which was one of several submitted by artists invited to create art for a garden setting, was installed in conjunction with an international design festival at the British Arboretum in Westonbirt, England, about an hour’s drive from London.

Basically, we went nuts with the opportunity. Adding to the fun was the fact that we were collaborating with an amazing landscape designer named John Thompson, a good friend of ours, a great artist and one who had begun his career studying traditional Japanese carpentry and working as a temple builder for several years.

For our sculpture, we crafted five 6-1/2- to 7-foot glass panels, each with a thickness of 3/4 inches. We used what is known as “float glass,” which has a texture on its surface, and applied silver nitrate (the same material used on the back of mirrors) to the glass before placing it in huge kilns for 24 hours.

We removed the panels and washed off the silver nitrate, which left behind a beautiful amber-colored hue. The glass looked fantastic: While they retained all of their translucence, when sunlight hit the glass they took on a phenomenally rich, warm glow.

We placed the composition in a large, shallow pond within a spectacular landscape dotted by all sorts of wonderful pieces supplied by other participating artists.

Andrey Berezowsky is co-founder of SWON Design in Montreal. He is an artist and designer whose experience spans some 30 years and whose passions have included furniture and industrial design, stained glass and glass blowing. He worked in Germany for five years with some of Europe’s finest glass and neon artists and has developed a knowledge of materials and processes that has allowed him to work in a multitude of mediums with refined skills and a knack for creating beauty. Michael Batchelor is the other co-founder of SWON Design. He worked as an assignment photographer for 17 years in an operation with offices in Montreal and Toronto and has worked for some of the top advertising and design firms in North America. In addition to his award-winning work as a still photographer, he has been involved in the film industry and also worked as a design and communications director for Sonnet Media, where he honed his skills in design, marketing and product development.