Digging the Quarry

Tucked into a small cove in the mountains behind La Quinta in California’s lower Coachella Valley, The Quarry Golf Club is hidden, ultra-private and basically unknown to all but members of the golfing elite and the wealthy few who play the course.

First conceived by entrepreneur Bill Morrow and designed by renowned golf course architect Tom Fazio, the course is a prime example of just how beautiful golf courses can be – and of how critical a role landscaping and watershapes can play in defining their character and aesthetics.

Our challenge was to embroider the course’s 18 PGA-sanctioned, championship-caliber holes with streams and planted areas worthy of the setting. At the same time, we were charged with designing the streams and ponds in such a way that they could handle runoff from a hundred-year storm while protecting the club from devastation.

It was a tall order, and one that proved both exciting and rewarding through each step of the process.

GRAVEL TO GOLD

Long before we at Pinnacle Design Co. became involved with the project, Morrow saw the site’s potential for golfers after visiting a course called Black Diamond in Lecanto, Fla. – a Fazio project that had been built on an abandoned stone quarry. As the story goes, Morrow was inspired by the irony of installing a prestigious golf course on what amounted to a wasteland, and he soon began a search for similarly discarded locations.

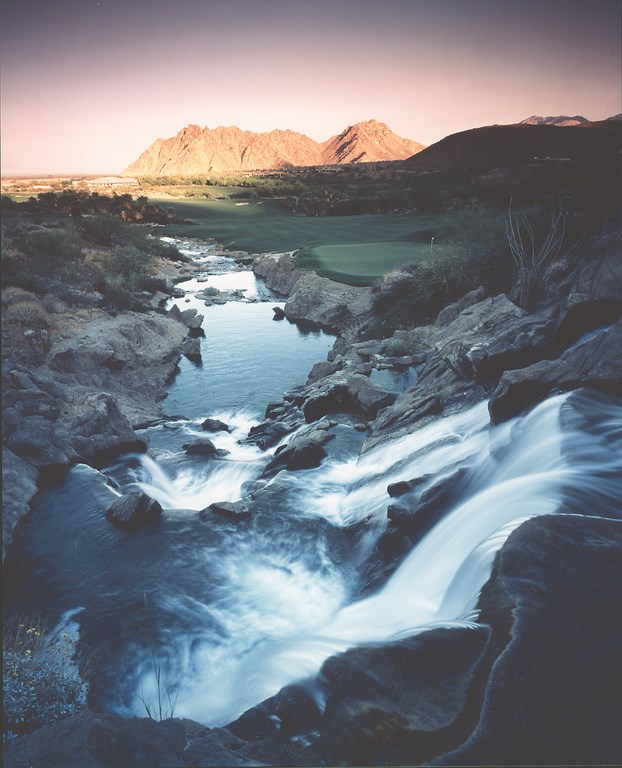

| RAGING WATERS: The waterfall is a system of artificial rockwork set atop a drop structure designed purely for function by the project’s civil engineers. As seen in the opening photograph (above) and examined outside the context of the golf course, it looks remarkably natural. Seen from a more inclusive angle here, with the deep greenery on the left contrasting with the high-desert foliage on the right, the naturalism of the waterway helps convey a sense that the golf course was draped over the land’s original contours rather than shaped and crafted in almost every detail. |

Morrow ran down his quarry in an abandoned sand-and-gravel pit that had been mined by Riverside County for more than 70 years to pave roads and highways. The ugly pit had been idle for years and was of interest to nobody but Morrow. After purchasing the land at a public auction (in which he was the only bidder), Morrow contacted Fazio, who immediately confirmed Morrow’s hunch that the topography and setting would make for a spectacular golf course.

Indeed, the course takes full advantage of its underlying landforms and now sits atop, on and below an alluvial fan that rises behind the exclusive enclave of La Quinta. Seven holes are on the valley floor, at the foot of the fan; seven holes are placed on the fan itself; and four upper holes are set in a cove that extends deep into the jagged mountainside.

In all, there’s a 300-foot vertical drop from the highest point to the lowest. This afforded not only some truly dramatic contours for the golf holes, but it also gave us spectacular topography to work with in setting up the “non-play” areas of the complex.

| ROLLING ALONG: There isn’t a lot of elevation change on the course’s lower levels, which gave us the opportunity to let the stream meander around the contours of the golf links in way that make everything appear more natural. |

Fazio and his design associate, Andy Banfield, decided that these three distinct sections of the course should also be equally distinct ecological zones reflected in the plantings and in the movement of the water. That in mind, we ultimately transformed a lifeless quarry into a riparian garden that features almost 4,000 feet of recirculating streams, four lakes, a massive waterfall run, hundreds of California fan palms and a rich palette of native and non-native plant species.

VIEW FROM THE TOP

Because of the site’s high degree of verticality and three distinct levels, we started by considering ways of moving the water from top to bottom – both the water that would be recirculating through the stream/pond system as well as the natural runoff that can appear, sometimes violently, in the form of the “gully washers” that hit desert areas.

Our overall strategy was to incorporate dry stream channels on the uppermost level along with functioning streambeds that would descend from on high to cross the face of the alluvial fan. Both the dry and wet systems would flow to a large drop structure and descend to the lower level, where a broad stream would feed a series of four large lakes on the valley floor.

| QUIET GRANDEUR: The fact that the lakes had to assist as catchment basins to accommodate the possibility of a hundred-year storm enabled us to take advantage of their reflective surfaces, letting them beautify the grounds as they serve their vital, practical role. |

This meant that the streambeds would have to be designed as aesthetic features that could double as drainage channels. The lowest of the four big watershapes on the lower course would similarly serve a dual role as a beautiful pond that would also serve as a holding basin in the event of a hundred-year storm.

The cove and alluvial fan offer spectacular views of lower portions of the course in the foreground as well as the date groves of La Quinta in the distance. Development of the previously undisturbed lower portion of the course was handled with great care so as not to disrupt the natural environment. To that end, access to tees, fairway drop zones and greens was all carefully cordoned off to minimize intrusions on the natural landscape. We also used the dry streambeds and other planted areas as “re-vegetation zones,” where plants salvaged during construction of the course were replanted.

|

Fine Lines The location and size of the water on championship golf courses is about more than aesthetics or irrigation: Indeed, what makes streams and ponds on golf courses a bit different from those in other settings is that water is part of the game itself. Because the water must serve as a hazard for players, there must be an extraordinary level of interaction and communication between golf course architects and landscape architects. That was certainly the case on this project. The overall design of the water systems is all based on lines of sight from the tees, fairways and greens and are set up in ways that influence the playability of the course. For example, streams on golf courses are typically located on the left sides of fairways so that right-handed golfers are less likely to hit their shots into the water. (Statistically, golfers at all skill levels will slice their shots to the right as opposed to hooking them to the left.) By contrast, the size, location and shape of still bodies of water such as the ponds and lakes typically seen near greens are carefully considered to provide enough of a hazard to make things interesting for top-flight golfers, but not to be so intrusive as to make the course unreasonably difficult for average players. — K.A. |

As you descend from the top level to the bottom of the alluvial fan, you move with streams that originate at dual headwaters adjacent to holes 7 and 16. We handled these headwaters in two different ways: On Hole 7, water emerges from a grotto set in the side of a slope; for Hole 16, a sub-surface return manifold fills a pond that spills into the stream.

Both waterways are small at first, representing only a small portion of a flow that is increased at several additional return points farther downstream. It’s a great illusion: Just as natural water gathers in volume and action as it moves to lower elevations, we wanted the streams in this system to increase in size as they moved to the lush areas on the course’s lower levels.

The streambeds are strewn with granite boulders of varying sizes, set in the water or arranged carefully along and near the banks. The plantings on this level are mostly indigenous and of more arid sorts than those found below, lending the space the feeling of a desert oasis. The streams and lakes are planted with a variety of aquatic grasses and other plants, along with several species of fish.

THE BIG DROP

From the start, one of the key components to the design was the 80-foot drop structure located on the face of the alluvial fan by Hole 10. The civil engineers who worked on the site designed the structure with a 50-foot weir that was capable of transmitting a five-foot wall of water to the lower elevations during a flash flood.

| THE WESTERN RANGE: Placed at key points around the grounds, bronze reproductions of Remington and Fraser originals lend an air of the Wild West to the golf club, hearkening back to people and events that might have been part of the fabric of the area’s life in its old mining days. |

As originally designed by the engineers, however, the structure was a drab, concrete eyesore of the kind you’d see in any number of municipal locations with similar topography and drainage requirements. To say this structure presented a challenge to the aesthetic integrity of the course would be a huge understatement.

We handled the issue as best we could, incorporating the dry structure into our wet design by using custom “rock cladding” to mimic the rock faces of the surrounding mountains and send our stream water over the weir. In this way, the structure could be used to create a dramatic set of vigorous, cascading falls in daily use while still being capable of handling a torrent under storm conditions.

The structure is further blended with the native terrain by virtue of thousands of square feet of colored concrete and rock formations made with gunite fiberglass-reinforced concrete (GFRC) sculpted and embedded with natural rock to create the effect of stabilized eroded-soil formations.

|

It Rocks We took all manner of approaches to rockwork at The Quarry. * The cobble and spoils used in the streams were all generated as a result of the screening process used to set up topsoil for the golf course. * More than 2,200 tons of limestone and granite boulders were imported to the site, where they were interspersed among indigenous stones in the streams and planted areas. * The artificial rockwork used on the drop structure consists mostly of pre-cast panels we made on-site using impressions from nearby rock formations. — K.A. |

As built, the drop structure indeed looks spectacular and is by most accounts a signature feature of the course. But if I had one thing to do over on this project, I would’ve worked to break up the linear appearance of the weir: As it now stands, its knife-edge is the only element in the watershape system that appears unnatural.

In any event, the stream picks up again at the base of the drop structure and eventually transitions into a series of four large ponds dressed in a variety of lush plantings. The flow terminates near Hole 9 in the largest of the lakes, where the water passes through a huge skimmer before being pumped back to the headwaters and other returns set up strategically along the way.

The streams re-circulate at a standard rate of 4,000 gallons per minute in (mostly) 18-inch plumbing driven by four 100-horsepower pumps that run on three-phase, 480-volt power service. When water is being added to the system courtesy of several nearby wells, the flow may reach as high as 7,000 gpm.

All of the water in the system is eventually used in irrigating the golf course and is continuously replaced, so there is no need for filtration. We did, however, use bottom-mounted bubbler aerators in the ponds to improve clarity and overall water quality. All of the pumps for the streams and the irrigation systems are in one location and controlled using a single computer system.

Well water is drawn into the system at Hole 10, just below the drop’s clubhouse. During summer’s blazing heat, the course requires approximately a million gallons of water per day for irrigation, with the need dropping to as little as a quarter of that level through the winter. Because all of the streams and lakes are designed to retain runoff from a tremendous storm, we set up considerable freeboard area in the form of broad, sloped shoreline contours that aren’t particularly noticeable to golfers who manage to hit their fairways.

All of the plantings are watered using drip emitters that are just wonderful for irrigating plants in an arid environment but also, as it turns out, are great at attracting wildlife – in this case, coyotes, rabbits and field mice who would routinely chew up the emitters to get at the water. For a time this seemed an unsolvable problem, but we finally decided to live with the animals and installed two small water sources and a couple of salt licks. Fortunately for the club and the animals, this strategy worked.

MOOD RIVER

Because of the way the course is designed, the watershapes reflect different moods in different locations.

The upper streams, for example, start out peacefully at a slow, meandering pace of 1,000 gpm between several intermediate pools. The streams gradually pick up in activity level as they approach the drop structure, where we accelerate things by adding water at a rate of 2,000 gpm to create a far more vigorous and active cascade.

At the base of the falls, things slow down again as the stream widens to create a sort of glistening, surface-riffle effect. There’s very little vertical transition at this level, and the streams move slowly toward ponds that complete the “narrative” by taking on a serene, reflective quality.

| OUT OF BOUNDS: Among the many objectives that made this project so captivating in a design sense was the amount of attention we were asked to give to non-play areas of the course. This helped us establish and communicate the three ecologies of the design program all around the fairways and greens and made it possible for us to let the land express its “natural” condition. |

The movement of water and the types of plantings tell their own story of how nature works in these sorts of natural settings. The indigenous, drought-tolerant plantings at the top transition through increasingly lush passages that conclude in the area with the most water. Here, we set up dense stands of California fan palms, flowering palo verdes, broad turf areas and a variety of ground covers and shrubs.

Much of the watershapes’ aesthetics can be enjoyed from the clubhouse, where the lakes spread out in a foreground view and reflect the surrounding mountains and beautiful desert skies. From there, you also see the waterfall’s dance over the drop structure in the distance. The streams trail back into the landscape, drawing the eye into the upper reaches of the course.

|

Group Effort The project described in the accompanying text could not have been completed without the skill and dedication of the following firms: * Fazio Golf Course Designers, Hendersonville, N.C. (golf course design) * Winchester Development, Scottsdale, Ariz. (project management) * Cook & Solis Construction, Escondido, Calif. (waterfeature construction) * The Larson Co., Tucson, Ariz. (artificial rockwork) — K.A. |

Although access is reserved to a handful of the private club’s members and guests, the golf world has nevertheless taken notice since the course opened in the late 1990s. In 2000, Golf Digest placed The Quarry among the top 100 courses in the United States – and it’s worth noting that the vast majority of the other courses on that list were established decades ago, with many dating to the early 20th Century.

One of the final touches on site was installation of a series of bronze replicas of famous bronzes by Frederic Remington and James Earle Fraser depicting wildlife and characters one might have seen in the Old West. The forms are elegant and whimsical and add grace notes to an exquisite setting.

These days, when I have occasion to visit the course at The Quarry Golf Club, I have a strong sense of pride and feeling of accomplishment in having taken part in creating such an inspired and inspiring landscape. Even more, however, I take delight in having helped to turn a lifeless and forgotten scar on the landscape into a captivating work of art.

Ken Alperstein is co-founder of Pinnacle Design, a golf-course architecture firm with offices in Palm Desert and San Diego, Calif. He is a 17-year veteran of the landscape-architecture industry and has specialized in golf course landscaping since 1989. Alperstein and his partners, Ron Gregory and Bill Kortsch, founded Pinnacle to serve the highly specialized golf course design industry. The company’s portfolio includes high-end championship golf courses, clubhouses and grounds throughout the Western United States – including several courses rated in the top 100 in the United States by Golf Digest and Golf magazines.