Avoiding Trouble

After years of serving as an expert witness in construction-defect cases, Paolo Benedetti knows what can happen when contractors fail to deliver the expected results. Here, he covers a set of practices aimed at keeping builders on the right path — and out of the courtroom.

After years of serving as an expert witness in construction-defect cases, Paolo Benedetti knows what can happen when contractors fail to deliver the expected results. Here, he covers a set of practices aimed at keeping builders on the right path — and out of the courtroom.

If you spend enough time as an expert witness in construction-defect cases, you begin to recognize patterns.

It’s easy, for instance, to tell when a project was likely executed by the lowest bidder – someone who had to cut all sorts of corners to come anywhere close to making money on a job. It’s also pretty easy to tell when an inexperienced builder has gotten in over his or her head, encountered something difficult and made a mess in trying to figure things out. These are the obvious sorts of issues that can be uncovered in even a brief forensic analysis.

But there are other actions, sometimes on the part of the homeowner but more likely on the part of a contractor, that can lead to trouble. These aren’t necessarily subtle mistakes; rather, they are clear errors of omission or commission that produce construction defects that lead homeowners to seek legal remedies – and can put builders squarely behind the eight ball.

Many of these issues arise because watershape construction isn’t the easiest business these days, with complex systems and design details that call for high levels of professional skill. To achieve quality results, a modern builder must be well trained and educated and provide expert, attentive on-site supervision to make certain everything moves along as it should.

There’s lots of wiggle room here, so let’s start narrowing the exposure by taking a look at what can happen when things don’t go so well because a builder’s education and experience aren’t on display – and then take a look at ways to help things move positively toward quality results and project success.

INSPECTION WOES

Let’s begin with inspectors and inspections: All too often, homeowners (and even builders) will rely on the expertise of these officials to inspire or demand good performance. The trouble is, building inspectors in many parts of the country are much less concerned with quality and workmanship than they are with basic “life safety” issues.

To some extent, it depends on where you live and/or work. All 50 states have adopted the International Building Code (IBC) for structures, for instance, but many do not apply those rules to the construction of swimming pools. This has led some states, including California, to adopt their own more-stringent codes to address specific issues relevant to their perceived regional concerns – and some cities within these states to adopt rules that are even more rigorous.

In Los Angeles, for example, local codes require soils reports, structural engineering and even a “special inspector” to monitor shotcrete or gunite application. These special observers aren’t inspectors, who can’t be tied up all day watching a shoot; instead, these are deputies who are prepared to hang around and watch the process for as long as it takes.

Over in Florida, the rules require that plumbing systems be completely specified to demonstrate that the plans fully embrace good hydraulic principles including specified line velocities and total dynamic head. In this case, the state recognizes that properly engineered hydraulic systems save energy, run more quietly and result in safer bather environments because the submitted line velocities do not exceed the capacity of the pipes.

| Inspectors play an important role, but their focus tends to be on safety rather than on calling out workmanship issues that might lead to construction defects. |

But if a job site is located in a jurisdiction that doesn’t take such issues to heart, chances are good that the inspection some might be inclined to rely on will be no guarantor of a defect-free construction process. And even if it is located in a diligent place, the fact that building codes are regularly updated and that it’s easy for inspectors to fall behind should make it clear: Inspections are great in several ways, but depending on them to help steer clear of construction defects is asking too much.

The same holds true of local building or planning departments. Some municipalities do not even require structural engineering (even though IBC requires it), so the contractor is left to do the right thing. Unfortunately, that involves money and, too often, the application of a “Hey, I’ve been building around here for years, what could go wrong?” attitude that can get everyone in lots of trouble should anything unexpected happen.

And even where structural engineering is required, it may not be site specific, meaning that it may not be sufficient to overcome key issues found on a given site. If luck is on the homeowner’s side, the wayward contractor won’t encounter unstable upslopes or downslopes, setback issues, building or structural surcharges (that is, objects close enough to apply stress to the shell), high water tables, loose or unsupportive soils or any of a number of potential environmental surcharges (seismic events, vertical shear planes, snow loads, avalanches, mudslides, tidal surges, storms or wind loads).

Generic plans won’t address these issues, but many contractors, once again in the interest of saving money, will trust a plan that makes no specific reference to the site at hand. And given the fact that most of these conditions exist under the surface, hidden from view, there’s no way to know what’s happening until the digging begins – by which point the occurrence of construction defects may be inevitable.

A BETTER PATH

So far, we’ve highlighted areas where things can go wrong. Let’s turn it around now and look at factors that will help everyone involved avoid the sort of hiccups that lead to major errors on a construction site.

First, everyone should be aware of the need for and insist on obtaining the appropriate professional support. Few watershapers have degrees in soils or structural engineering; without such an education and the appropriate licensing, it’s folly to move forward with a project because nobody can know what’s required to build safely and securely on an unexamined site.

Look at it this way: The average swimming pool is like a basement filled with water. Would you and your family be happy living over that basement if the builder was just guessing about how thick the walls needed to be or what sort of steel schedule was required to enable those walls to withstand unknown pressures being applied to the outside of the shell?

That would be hugely risky (and a bit crazy) – but for some reason there are always contractors out there who think they know enough to get by. Again, as a professional watershaper who’s performed lots of forensic examinations of failed pools, I would never put myself in so vulnerable a position: Get real, science-based inspections – and use the results well.

| Pool construction is increasingly a high-stakes business, making it too risky to proceed on site without proper soils testing to guide a structural engineer’s recommendations. |

Second, play by the professional rules – even in states where licensing isn’t required. It’s tough going in Texas, for example, where contractors don’t face a licensing requirement and therefore pass no competency exams or post any sort of bond and the state neither registers nor investigates any complaints. The only recourse for property owners under these circumstances is litigation.

If I’m working in a jurisdiction of this sort, I do all I can to encourage prospective clients to be very deliberate about due diligence, checking with the Better Business Bureau and interviewing contractors’ past clients for starters, then digging deeper with detailed Internet searches that go way beyond the first couple pages of references. Check court records to see if the contractor has been involved in many lawsuits and contact the complaining parties for the reasons behind the suit. Sometimes the contractor will be in the clear, other times not.

And even though information sources such as Yelp! can be less than reliable, I suggest checking there, too, because any feedback at this point helps draw a clearer picture.

I also advise both homeowners and contractors to take lots of pictures of the construction process, starting on Day One. This step represents a sensible level of self-defense on both sides of the relationship. In fact, the construction defect cases that are the easiest to settle are those in which thousands of images have been collected. And it’s good to use a high-resolution smart phone or camera: The ability to zoom in for close looks can be most illuminating.

Large images also allow for comparisons of scale, which helps determine the precise placement of objects during construction and allows for accurate, adequate assessment of workmanship as well as the care used in adhering to plans and contracts. I also like to think that photographs are like sunshine: The fact that the process is being recorded is generally a good way to put a contractor on notice that someone’s paying attention now – and that more authoritative folks may be taking a close look later if things go seriously wrong.

Finally, images can obviate the need for destructive testing: If there are photographs that fully document the process, for instance, it’s less likely that it will be necessary to cut cores out of walls, floors and slabs to determine the quality and strength of the concrete or that it will be necessary to bring in a side-scanning radar to locate reinforcing steel and document its placement and depth. These are expensive procedures that can often be avoided if there are lots of good pictures on file.

BE PREPARED

Even if you’re a great contractor, things can sometimes go wrong. Photographs can be helpful in determining what has happened, but it’s also important to make lots of notes – and for both the contractor and the homeowner to maintain organized job files that include daily progress reports and highlight such details as weather conditions that might have had an effect on a day’s operations. This is also a helpful way to document scheduling commitments, change orders and project revisions.

All paper moving back and forth should be numbered and dated, including any drawings made on the spot to indicate a necessary variance from a plan. Emails should be saved and logged along with notes on any phone or in-person conversations. The results should be filed in a convenient binder – one that can be disposed of properly if everything goes smoothly but will come in handy if there’s a bumpy ride.

| Maintaining records and taking photographs is laborious, but in an environment where homeowners track the process daily in great detail, contractors need to step up and do it, too. |

I know lots of homeowners for whom maintaining this sort of process documentation comes naturally. By contrast, it’s rare for a contractor to be so organized. As mentioned above, however, this process is all about self-defense on both sides of the equation, and I would seriously recommend stepping up and becoming a diligent record-keeper no matter which side you’re on.

Who will a judge or jury believe? A well-organized homeowner or a confused and disorganized contractor who contradicts himself or herself because he or she failed to make adequate notes and keep adequate photographic records? I won’t let myself be caught at such a disadvantage. And again, I see a wonderful self-regulating, self-policing effect in knowing that everyone’s paying attention!

And speaking of regulation and policing, the importance of knowing and following applicable building codes is of great importance in watershape-construction. These codes are, in effect, the laws adopted by local governments to ensure use of minimum acceptable construction standards and are constantly being updated and expanded with a general trend toward becoming more stringent.

There are also industry and trade guidelines that serve as workmanship standards applicable to various trades and sub-trades. These are the law in civil courts: When a project experiences overt signs of poor workmanship, the legal system will ultimately get around to comparing what happened with what was supposed to happen.

Many of these trade standards are referenced in the building codes. IBC, for instance, refers to many of the American Concrete Institute’s standards, even going as so far as to incorporate them into the code. The same goes for plumbing, electrical, tile, masonry, shotcrete/gunite, plaster and other trades.

For purposes of this discussion, I’ll accept the value of minimum standards in clarifying performance on a job site. It should go without saying that a quality business will exceed those minimum standards in the course of delivering quality results. In this context, standards form baselines – and all contractors who perform quality services will operate well above those marks.

PLAN ON IT!

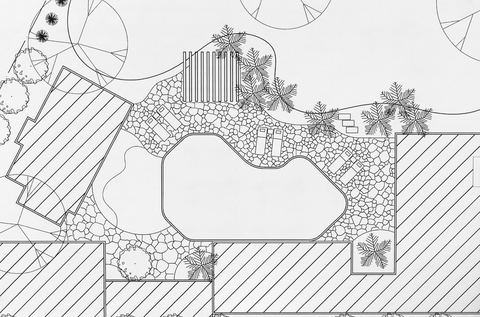

In some of my expert witnessing, I’ve come across projects for which the documentation consists of a plan that does little more than indicate where a pool and the associated equipment pad will be located on site. This single sheet is accompanied by a page of generic structural engineering.

Of all the elements that can help a project go right, there’s none more important than doing far better than that by way of project documentation.

A thorough set of plans should include the project layout or plot plan as well as: project cross-sections and elevations; grading elevations (both rough and finished); a surface run-off and drainage plan (and a special urban run-off plan, if applicable); and a gas and electrical service plan running from the street to the equipment pad.

| This plan seems nice enough, but it only has value if it’s backed up by dozens of pages of supporting documentation that serves to take as much wiggle room out of the construction process as possible. |

There should also be schematics for low-voltage and high-voltage conduits; suctions and returns; spa-jet suctions and returns, jet placements and placement of associated air lines. There should also be lighting schematics (covering placements and wattages) and a complete layout of the equipment pad, to scale, with a project-specific materials list.

The equipment pad sheets should be backed up by wiring diagrams, electrical load calculations and sizing notes for breakers and wiring. There should also be construction details, cross-sections and notes along with construction specifications, information on waterproofing measures and various project-specific notes on local codes as well as safety and anti-drowning features. Finally, there should be a comprehensive listing of applicable codes and standards, with full references and applicable dates.

If a project is this well defined and specified in advance of construction, the client has a tool to use in keeping the builder on track; flip side, it leaves the contractor precious little wiggle room and can play a major role in helping him or her see the wisdom of bidding properly and not cutting corners in ways that deliver a less-than-optimal product. As I see it, spending money here and working with well-prepared, thorough plans can save thousands later on in attorney fees, reconstruction costs and charges for loss of use and stress.

It’s an environment where, if you pay for quality, you only have to do it once. As one who has spent a lot of time testifying on behalf of aggrieved homeowners against contractors who tried to walk a different path, that guiding philosophy is sound – and should be applied in watershape construction no matter where it takes place.

Paolo Benedetti is principal at Aquatic Technology Pool & Spa, a design/build firm based in Morgan Hill, Calif. He may be reached at [email protected].