WaterShapes

Sometimes the simplest ideas shine the most brilliantly. Take water, for example: For all the complexity of "shaping" it with hydraulics, chemistry, structural engineering and dealing with the hard-line issues of technology and craft, it's the hypnotic, aesthetic and even spiritual qualities of the material that ultimately

The history of modern swimming pools really dates back just a hundred years or so. Yes, there are examples of pools, baths and other watershapes from the distant past, but the swimming pool as we know it is something that truly emerged during the 20th Century, mostly after World War II. Before then, there were probably no more than 50,000 pools built in all of the United States - and most of those were seen as something quite special for their time. Nowadays, we're far enough into the development of "modern" swimming pools and other watershapes that a small number of "antique" pools have been declared historical landmarks, with those at Hearst Castle being

When asked what an "optical physicist" does, I sometimes reply that I'm basically a professional choreographer. What I choreograph, of course, is not lithe dancers in leotards and toe shoes, but rather the countless invisible balls of energy whose source, directly or indirectly, is our sun. That's a colorful description, but it accurately reflects the fact that I've spent my entire professional career coaxing, urging, manipulating and orchestrating light in a completely conscious manner with tools both simple and complex. Armed with a liberal arts education and majors in art history and American studies, I founded an industrial-laser company in 1983 and spent the next 18 years learning how to choreograph balls of energy into extremely precise line dances. There was nobody out there to teach us

I may be revealing a professional bias here, but ozone is fascinating stuff. In nature, it's among the most essential chemicals on the planet, existing most prominently as a gaseous component of our upper atmosphere. Formed there by sunlight's reaction with atmospheric oxygen, it collectively constitutes the famous Ozone Layer that protects us from the sun's ultraviolet rays and is crucial to the very existence of life on earth. Closer to the ground, ozone is widely used across a broad spectrum of applications. It's well known in the pool and spa market as a water sanitizer, for example, either as a chlorine alternative or an adjunct. It's also widely used in food processing and municipal drinking and wastewater treatment systems and plays key roles in the production of cosmetics and with air freshening and purification systems. For all that, one of the most interesting applications of ozone-generating systems in the past 20 years - and the subject of this article - is the use of ozone in the life-support systems for aquatic animals held in captivity or for

I've always been conservative when it comes to guaranteeing my work, which is why I only offer a 300-year warranty on my sculptures. I'm fairly certain that the vast majority of my pieces will last well beyond that span, but there's always the possibility one might be consumed by a volcanic eruption, blown up in disaster of some sort or drowned when the ice caps melt and cover the land with water. Those sorts of cataclysms aside, it's hard to imagine that the massive pieces of stone I use to create what I call "primitive modern" art will be compromised by much of anything the environment or human beings can throw at them. Ultimately, that's one of the beauties of working in stone: It possesses a profound form of permanence - and there's a certain comfort that comes with knowing my work won't be blown away by wind, eroded by rain or damaged by extremes of heat or cold. And given the fact that these pieces are so darn heavy, it's safe to say that most people are going to think at least twice before trying to move or abscond with them. Beyond the personal guarantees and despite the fact I don't dwell on too much, working with stone also has a unique ability to connect me and my clients with both the very distant past and the far distant future. Human beings have been carving stone for thousands of years, and many of those works are still with us in extraordinarily representative shape. There's little doubt that those pieces

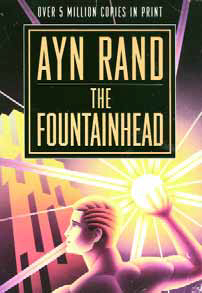

Every once in a while, I find it useful to read something purely for inspiration. Especially as the busy season heats up, I truly enjoy the thought of stepping away from the grind and getting lost in the pages of a good book. Most recently, I picked up Ayn Rand's classic, The Fountainhead (Penguin Books, 1994), and found not only a terrifically entertaining story, but one that I also see as useful on the professional front because of its many insights into issues of creativity, design and personal integrity. Let me start by saying that I'm not offering this unusual entry as an endorsement of Rand's controversial philosophy. There are plenty of ideas presented in this long, 700-plus-page book that don't align with the way I see things, and I have no intention here of commenting on Rand's "objectivism" in any way. To me, the core of the story is

In last month's "Detail," I discussed the beginning stages of a new project that has my partner Kevin Fleming and me pretty excited. At this point, the pool's been shot and we're moving along at a good pace. I'll pick up that project again in upcoming issues, but I've brought it up briefly here to launch into a discussion about something in our industry that mystifies me almost on a daily basis. So far, the work we've done on the oceanfront renovation project has been focused on a relatively narrow band of design considerations having to do with the watershape and its associated structures. This focus is

Think of it: Just below the surface of our ponds and streams is a wonderful potential for beauty, an amazing opportunity to open observers' eyes to an entire submerged "landscape" made possible by virtue of completely clear water. I like to picture it as an "underwater garden," which is why, to me, water clarity is an essential component of my ponds and streams. Too often, however, I run into settings in which it simply has not been a priority for the designer or installer. I'm further distressed when the subsurface views I treat as key design elements are left partially or wholly unconsidered. I think back to my family's trips to the seashore, where we would spend hours observing rocky tidal pools. Peering into the water and seeing a world of oceanic plants and animals at close proximity was a profound source of fascination and excitement. It is for me still – and, I believe, for most other people as well. What I see in tide pools is a perfectly balanced, utterly natural underwater garden filled with beautiful stone colors, textures weathered by the action of the waves and tides and a plethora of pebbles and sand mixed with bits of seashell. It is here that we may

Recent times have seen the introduction to the pool/spa industry of a new breed of hydraulic pumps that use what is known as 'variable frequency drive' technology. Here, watershaper, hydraulics expert and Genesis 3 co-founder Skip Phillips describes why he believes these devices, which have been used successfully for years in other industries that demand hydraulic efficiency, represent the future for pools, spas and other watershapes. For all the progress made in recent years to change the nature of the game, to this day I still see situations in which pumps, filters and other system components for pools, spas and other watershapes have, hydraulically speaking, been completely

Working in constrained spaces is entirely different from tackling projects that unfold in pastures where the only boundary might be a distant mountain or an ocean view. Indeed, in small areas that may be defined by fencing or walls or adjacent structures, the constrained field of view offers substantial aesthetic challenges to the designer in that every detail, each focal point, all material and color selections and every visual transition will be seen, basically forever, at very close range. When you're working small spaces, in other words, there's literally not much room for error. In this smaller context, each and every decision watershapers and clients make will subsequently be in direct view, and it's likely that each detail will take on special significance for the clients, positive or negative, as they live with the watershape over time. And on many occasions, what we're asked to start with as designers leaves much to be desired, including spaces already vexed by sensations of confinement, closeness or downright claustrophobia. To illustrate what I mean, let's take a look at two projects I recently completed in smallish yards for clients who wanted to