Making the Wild Waters Flow

Graced by an abundance of beautiful, natural streams, cascades, rivers and lakes spread across spectacular native landscapes, Utah is a dream location for watershapers.

Not only is there a rising demand for crafted streams, ponds and cascades that look like they really belong, but the state itself is also a genuine design laboratory. Indeed, I send our crews out into the “wild” periodically to do nothing more than hike up and down local watercourses to see how Mother Nature does things. These waterways are easy to find, and the exercise (both mental and physical) keeps us all fresh.

The steady contact with nature is a big help in our creative endeavors: I’ve found that even the most talented and conscientious watershapers can fall into design ruts if they spend too much time with their noses to the grindstone and don’t get out and about to seek inspiration. Once the batteries are recharged, we’re ready to participate in projects we all see as functional works of art.

DOWN TO BUSINESS

My company, Bratt Water Features Inc., is a wholly owned co-operative with Bratt Inc., one of the largest landscape design/build firms in the country. We pursue both commercial and residential projects, mostly upscale, and about 60% of what we do is best classified as commercial. Reflecting that balance, two of our three crews focus on commercial work, while the other specializes in residential projects.

Most of our jobs start with our landscape architects, who conduct the initial meetings with clients, set basic project parameters and carry things through to preliminary drawings. Once it’s determined that a project will include a watershape of some kind, our waterfeatures division steps up and joins the design team.

At that point, I start discussing the project and various ideas with our architects, determining whether, for example, the watershape will have an architectural or natural appearance and getting some idea of desired flow rates and volumes, basic visual elements, key vantage points and, in a more general sense, the overall “mood” of the feature.

Case #1: A City Creek

Located in downtown Salt Lake City adjacent to the LDS Conference Center and across from the Mormon Temple, this project was challenging because we were working with a swath of land just 15 feet wide in which we were to create a meandering and believable mountain stream.

The system makes up in length what it lacks in width, running for 525 feet with about 20 feet of vertical transitions and three pedestrian crossings that provide key vantage points for the stream and its large boulders, big cascades and dense plantings. The key to pulling this off visually is tremendous variation in the size of the boulders and the way the pockets of plant material are dispersed amid the rock formations, along the edges and in the streambed itself.

Another integrating factor is that the rock came from a quarry owned and operated by the Mormon church – the same quarry that provided stone for the conference center and the temple. By using this material, we were able to visually align the stream with the landmarks surrounding it.

Often, we’ll move through three or four different options developed to the point where they’re discussed with the developer or homeowner, and ultimately we arrive at an overall design scheme. Generally speaking, these are free-flowing, immensely positive creative processes, and we use them as a means of setting expectations for how the project will proceed and what clients can expect to see once we’re finished.

We also develop the budget during this design/planning stage. To speed the process, we show clients photographs of past projects and use them to define levels of detail they want to see and enable them to align their desires with relative levels of cost. For large bodies of water, those details and costs can vary substantially based on the client’s wish list. Once this part of the discussion is settled, we begin developing more definite plans.

Occasionally, we run into developers and other commercial clients who’ve had difficult experiences in the past with large waterfeatures. This is actually helpful in the long run because they’re aware of the kinds of issues that can arise, but in the short term it puts us in the position of talking through potential problems in great detail by way of reassuring them that we know what we’re doing.

Usually, our belief that these are positive exchanges of information and that great things will ultimately be accomplished wins out: By the time we’re through, the topics of discussion change from what might go wrong to productive conversations about good hydraulic design, the achievement of credible natural aesthetics and getting the most from whatever budget has been set.

Another reason developers are willing to engage in the process of watershaping is because, despite any troubling past experience, there’s an increasing acceptance of (and demand for) water in public spaces, commercial settings and residential developments. In a nutshell, these entrepreneurs and enterprises recognize the part water has to play in distinguishing and adding value to their properties.

OF A PIECE

Our aim in the design/build process is to deliver a watershape that blends in perfectly with the overall landscape setting. As a result, integration is on our minds from the start.

We always think of what we’re doing as an exercise in working within the context of fully designed landscapes (often very large landscapes), and we see a clear advantage in placing the water elements within those settings in such a way that observers gain a sense that our watershapes truly belong where we’ve put them.

This is probably easier for us in our waterfeatures operation than it might be for firms who only do the watershaping, because we know and work with our company’s landscape architects all the time and know the control they have over the planting plan and the hardscape design. We use this intimate contact with the overall project to inform what we do with the water.

We’re all in the same co-operative, so we share ultimate responsibility for the way the project proceeds. And this is just as true in planning and designing residential projects as it is for commercial work – although it’s fair to say that we tend to find much more freedom on residential projects than we do on the commercial side.

Case #2: Provo Estate

This estate, which is draped across a mountain and part of an adjacent valley, was undergoing massive renovation when we were called in to install a waterfeature off to the side of the main house and near a patio for a greenhouse. There was a waterfeature there already, but it was little more than a trickling eyesore – so much so that the owner was hesitant about replacing it with anything substantial.

Once we overcame his misgivings, we set up a deck that cantilevers slightly over the main pond to provide a great view of the cascade, groundcovers and aspens. (The railed walkways were an afterthought and, in my opinion, detract from the overall appearance – although they do provide a level of safety.)

In an odd twist, a homeowner who originally hadn’t wanted a watershape decided that he wanted fish – but that the water could be no more than a foot deep because of his concern for his children’s safety.

After advising him that success with koi and other specimen fish required water that would be at least three feet deep in places, we compromised by digging the pond to an adequate depth for the fish, then filled it in with 18 inches of gravel. For now, the pond is both shallow and devoid of fish. Later, the gravel can be removed and fish can be added without any need to renovate the pond.

The system runs on two five-horsepower pumps that create an extremely vigorous flow over the falls. The pond’s overflow capacity was greatly diminished by the gravel filling; to meet the need for extra capacity in the short term, we located a holding tank off to the side below the deck.

Either way, it’s basically a process of defining basic shapes and the ways they all fit together in the allotted space and of putting those relationships down on paper. Most of the time, the finished product will differ, sometimes in significant ways, from our initial sketches or drawings – we are, after all, dealing with real boulders, stones, plants and free-flowing water – but through open communication we’re able to prepare our clients for the journey toward completion, whatever turns we all might take.

This works because our installers have become very good at designing fine aesthetic details as part of the flow of construction. Indeed, they’re required to display a certain spontaneity and a high level of artistic expression on site as we seek to mimic nature, and I’d go so far as to say that the more exacting the aesthetic details we create on site, the more believable the work ultimately turns out to be.

This attitude and philosophy gives our installation crews a great deal of independence in determining precise details of waterfall construction, edge treatment and headwaters configuration as well as integration of plantings and placement of rock material. We look at it this way: Every site is different, and being out there on the job gives installers a “feel” for the space and its viewpoints and a superior ability to understand the visual connections that can be made within the setting.

In other words, I believe we’re at our best when we develop a good, comprehensive, interpretable plan and can cut our crews loose and let them create – another reason I’m so intent on having them all get out, clear their heads and spend some quality hiking time in observing and understanding nature.

GETTING REAL

Improvisation with finish details is one thing, but we’re much more concrete at the planning stages when it comes to issues such as elevation changes, overflow designs, plumbing configurations, equipment locations, power service and site access.

These are issues that always must be sorted out ahead of time so that the installation can go smoothly and everything will work properly once the project is finished. In fact, all those issues can greatly influence our work on site, which means we place a premium on having them settled so our crews are free to consider the finer details.

Overflow capacity, to take one example, can have a significant influence on the volume of water the system can contain and thereby can affect the entire upstream design. The same is true of the extent and character of elevation changes and of location of the primary viewpoints. Once we’ve surrounded all of these issues and have established a general working plan for aesthetics, it’s finally time to roll in with the earthmoving equipment and begin shaping the space’s substructure.

Case #3: Executive Retreat

Part of the Provo estate covered above was set up for non-family use and now includes several cottages set up as a retreat for personal and business guests.

The overall property contains several beautiful natural streams, but none were near the guest lodgings. To change all that, we were brought in to create a waterfall/stream system that would fit in visually with the existing natural streams and add the soothing sound of water to the retreat. This stream stretches 400 feet up the hillside to headwaters tucked in a forested area. The idea is to draw visitors up the hill and into the wooded area.

In keeping with the contemplative mood of the area, this stream is less vigorous than the one at the main residence, offering gently babbling cascades that descend along a rocky streambed. All of the rock for this stream was harvested on site and used liberally in the stream course, and the result is a manmade watercourse that fits in perfectly with the property’s natural streams.

This is a time of care and precision: We set our benchmarks for elevations, mark precise locations for waterfalls, spray paint the basic layout – and maintain constant contact with the clients, architects and our own crews to be sure that everyone is visualizing the same things.

This phase is particularly important for projects with elevation changes, for the simple reason that water flows downhill. To be sure, the transitions can be set up with cascades that exploit the visual potential, but it’s also true that it’s possible to overstep the bounds and create cascades that are overly dramatic and end up causing unexpected problems with excessive noise and/or splash out.

Once we’ve excavated the site and are satisfied with the stream course and the location of the ponds, our next phase involves plumbing installation. We typically start at the top and work our way down to the pond or holding pool (or the surge tank, if we’re working with a disappearing stream).

Next, we lay down geo-textile fabric to help protect the 45-mil EPDM rubber liners we use, topping the liner with another layer of fabric for added protection. To be absolutely sure in places where large rocks will be set, we’ll also lay down a three- or four-inch layer of polystyrene padding: This protects the liner from being pinched or creased by big boulders and gives us some much-needed flexibility in shifting the boulders to expose their most desirable contours.

FLEXIBLE DURABILITY

As a rule, we work with EPDM liners rather PVC liners, but it’s largely a preference based on our local climate and our observation that EPDM liners stay more flexible at lower temperatures than do PVC liners. We also like the fact that EPDM liners last 20 years even when exposed to ultraviolet light: Our liners are all completely covered either by concrete or gravel, hence no UV exposure – and some extra confidence in the material.

The liners aren’t fragile per se, but we’re careful in placing them to avoid pinches and snags. And we’re particularly deliberate in thinking things through and making certain we aren’t creating points where they’re likely to leak or flood – especially important as we close out this phase of the project and start working with the stone.

Safe to say, the selection and placement of boulders is the key to the whole process of creating naturalistic waterways. As a result, we spend a great deal of time in getting things just right. We work primarily with granite and quartzite as well as some basalt and limestone. Everything is mined locally, and we generate some of the material ourselves through our excavation work on various projects.

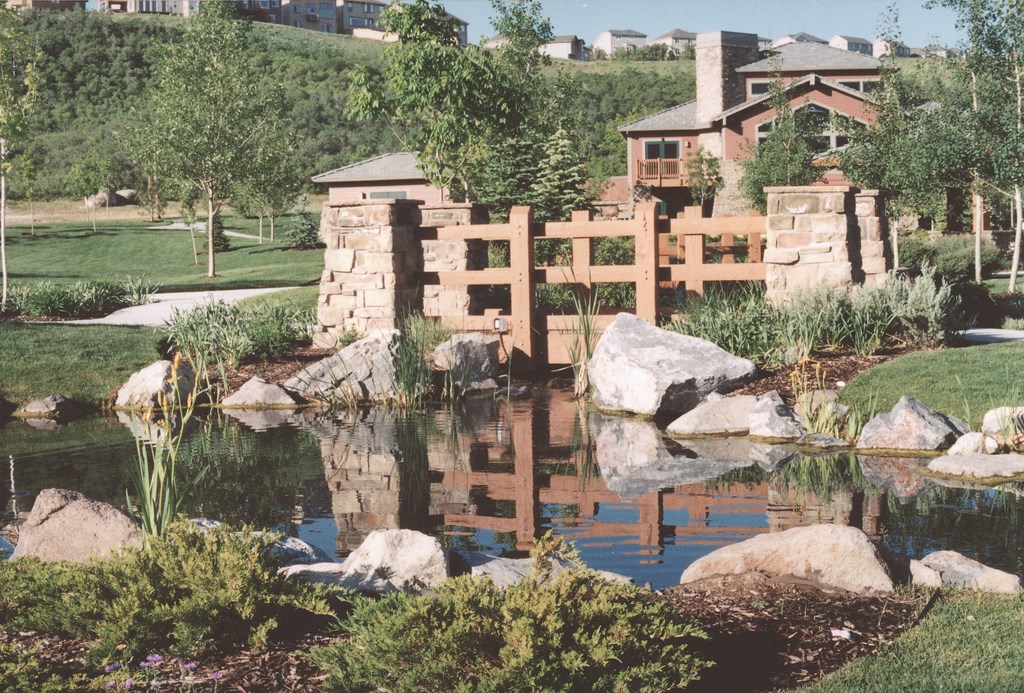

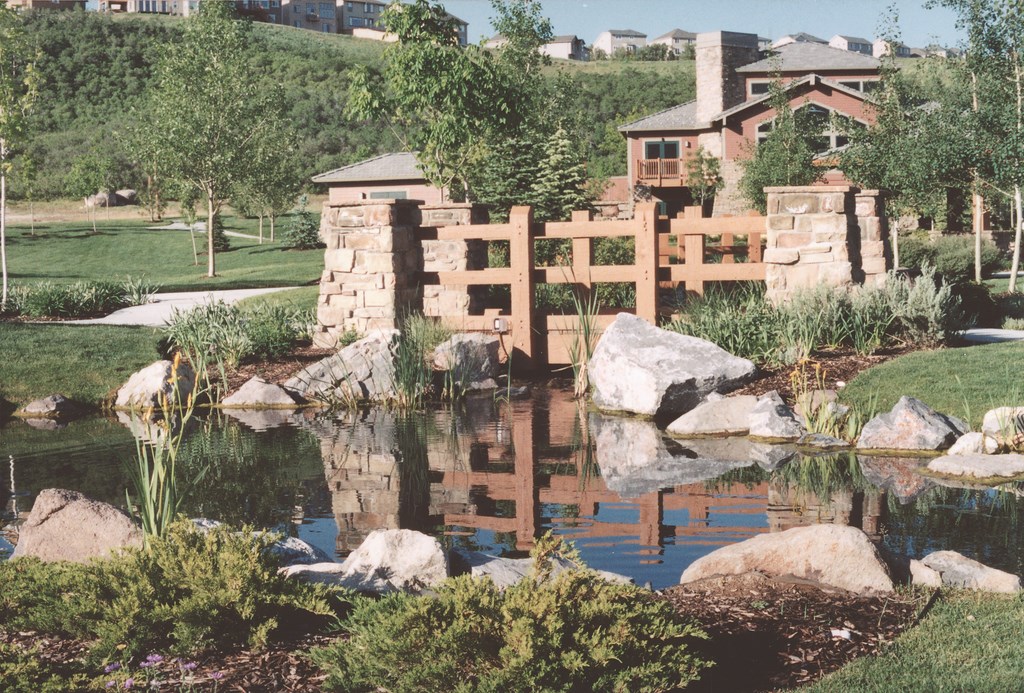

Case #4: Suncrest

This watershape is located near the entrance of a new residential development on a ridge above Salt Lake City at about 6,000 feet in elevation and constitutes a classic example of a developer seeking to use water to add interest and distinction to a space. The headwaters are near the development’s information center and offer visitors a spectacular introductory view.

Our goal was to create a setting that had a park-like, mountainous feel and would provide a place where prospective buyers might stroll and take in the surrounding beauty and tranquil waters. To that end, the stream operates year ’round, includes several large ponds and cascades and is stocked with trout. For a watercourse of this size, the flow is at a relatively modest 600 gpm – just what we need to keep the water from freezing. And in the thick of winter it provides breathtaking views of snow, ice and water.

Of particular interest, several hardscape features are also integrated, including architectural bridges, pergolas and stone walkways that cross over or offer great views of particular points of interest along the waterway. Landscaping was also critical to lending a natural feel to the overall surroundings. The rock was primarily a very hard limestone quarried locally.

We like using rounded granite boulders in streams because the overall impression harmonizes with the appearance of natural streams we see all the time in this area. But there’s a challenge in using mostly rounded material in creating cascades, because the water will tend to hug the surface of a rounded boulder and won’t “break” the way it will off sharper surfaces.

This is where the quartzite, limestone and basalt often come in handy, but there are occasions when only granite will do, which is why we’ve developed a technique for using a large track-hoe excavator to drop boulders on one another for the purpose of breaking them and creating flat planes we can use. This takes some care: The collisions can send shards of rock flying at high speeds in all directions!

We go to all this trouble because we want to avoid using flagstones to set our weirs. So often, a flat piece will be totally out of context, and it’s just too obvious that someone has placed a stone there to create a waterfall. Our creed in such matters is simple: The true test of the aesthetics of a stream or waterfall is how they look when there’s no water flowing at all. Flat weir stones simply don’t pass the test.

Once the boulders are all in place, we’ll come in with concrete and pour it around the large rocks and waterfall transition areas. While it’s still wet, we embed cobble in the concrete and then fill in any gaps with gravel. When we’re done, you can’t see any concrete or liner.

We do experience a great deal of cracking because of local freeze/thaw conditions – which is ultimately why we use liners along with partial concrete surfacing. This helps us control costs – and dodge the fact that it’s often hard to conceal large expanses of concrete in natural-looking ways.

STARTING THE FLOW

We apply the same attention we do in setting up natural-looking weirs to the job of establishing our headwaters. As a rule, we set things up with pipes that introduce water to the bottom of our upper ponds, covering the manifolds with rocks and allowing the water to well up and spill naturally into the watercourse.

But that oversimplifies things a bit, because deciding where the headwaters will be in the overall water system is crucial to believability. I’m disappointed, for example, when I see water emerging from the center of a berm or slope. Nature doesn’t work that way. Instead, we’ll set the headwaters at the crest of a slope or tuck it out of sight among plantings or rockwork – or even in a structure of some kind.

And whenever possible, we’ll establish multiple headwaters outflows to lend the watershape a sense of variety and even greater believability. In our experience, this approach of introducing the water at multiple locations and at varying elevations gives us greatly expanded options for separating and conjoining streams, for example, or for creating pools or rapids and manipulating the way everything sounds.

Our target flows for cascades are about 60 gallons per minute per lineal foot, which means about an inch and a half of water moving over the falls – vigorous but not overwhelming. Obviously, that target will move up or down, depending on the design. But as an average for entire systems, the 60-gpm-per-foot standard holds up remarkably well.

As we move downstream, we’re aware of the fact that plantings are as important as rockwork in conveying the visual impression of natural waterfeatures. Through the years, in fact, we’ve moved further and further along in our understanding and use of aquatic plants and of ways of bringing groundcovers right up to the water’s edge and into the streams. We work a lot with marginal and bog plants as well as water lilies and floating hyacinths. We’re also working more often at creating suitable environments for fish.

Again, our aim is integration. In our initial designs, we incorporate pockets where plants and groundcovers can take hold and spread out among and over the rocks and set up areas where we can use perennials or other plantings to add color and accentuate viewpoints.

If one side of a stream will be viewed more than the other, for example, it makes sense to locate plants with lower profiles on the vantage point’s side and place taller plants on the other side. Instead of blocking critical viewpoints, these tall plants and trees can be used to draw the eye up from and beyond the stream.

Our watershaping process is detailed and deliberate, and everything flows from knowing where we’re heading right from the start. This knowledge, this capacity for all of us to be on the same page and visualizing the same outcomes, has enabled us to meet our clients’ demand for quality, take our place in pursuing what we all see as an emerging art form – and still have time to take the occasional walk along a stream.

Derk Hebdon is owner and president of Salt Lake City-based Bratt Water Features, a spinoff of Bratt, Inc., Utah’s largest landscape design and construction firm. A 1991 graduate of Arizona State University, Hebdon started in the landscaping design/construction trades in 1992, when he purchased a landscape maintenance and construction firm in Tampa, Fla. In 1995, he moved into the design and construction of ponds and streams – which quickly became a primary focus for the firm. He sold that business in 1999 before moving to Utah to become manager for Bratt’s waterfeatures division. That business unit was spun off in April 2003 and now focuses on designing quality waterfeatures for residential and commercial clients. Hebdon is a certified landscape professional (CLP) through the Associated Landscape Contractors of America.