Historic Perspectives

There’s something truly wonderful about working on properties that are in one way or another historic: In a very real sense, they give you a rare opportunity to participate in the past while at the same time you are conceiving and forming a place for the future.

This project is a case in point: My endeavors here gave me the chance to beautify a truly splendid 1905 private home in southern Wisconsin and complement its amazing Palladian/Greek Revival-style bone structure with a contemporary composition in rock, plant material and water.

The owner, who has a passion for architecture and historic preservation, had already completed a total restoration of the buildings. The grounds, however, still left much to be desired. The property manager had worked with me on a previous project, and he suggested that I should be brought in to revitalize the space – the centerpiece of which would turn out to be a grand system of ponds, streams and waterfalls.

SETTING THE SCENE

The mansion faces a lakefront to the south and is backed by approximately 35 acres of mostly forested land. To the front of the home is a lawn that covers an expanse running from 300 to 400 feet down to the lakeshore and a private dock. The site rises gently from the water’s edge, eventually reaching mature oaks, maples and other assorted species that have been there for 100 years or more.

| This is the property as it appeared before construction began, complete with an existing pond couldn’t be detected from the house other than as a fountain spray rising awkwardly from the lawn. As can be seen here, the slope rises very slightly and gradually through much of the deep available space, with a distinct grade change occurring mainly in the upper third of the space. |

It is truly a noble setting, and fortunately, the new owner had the architectural knowledge and enthusiasm to restore the entire estate to its original grandeur.

I was called in initially to address the property’s rather scruffy little pond – a thing that did not do justice to its surroundings. It was extremely small and sat at the bottom of steep banks, so the water was invisible from the house and only discernible when you were almost on top of it. One was made aware of its presence only by an ornate fountain spray that rose above the banks and the beds of waterside plants. Aesthetically, none of this worked well, and the pond always seemed half empty.

I have always disliked the look of half-empty ponds: They remind me vividly of the bomb craters that used to dot the countryside where I grew up in southern England in the 1950s. Out in the fields, I’d encounter these random holes, which often were partially filled with water, and disliked them because they looked so unnatural and alien to the landscape. (This is probably why, to this day, I’m such an advocate of brimming water.)

Eventually, of course, those countryside craters were filled in and erased from the landscape, and that’s exactly the fate I intended for this pond. Indeed, in my very first discussion with the client and the property manager, I suggested that the existing watershape was so thoroughly inadequate and that it would be best simply to wipe the slate clean and start again.

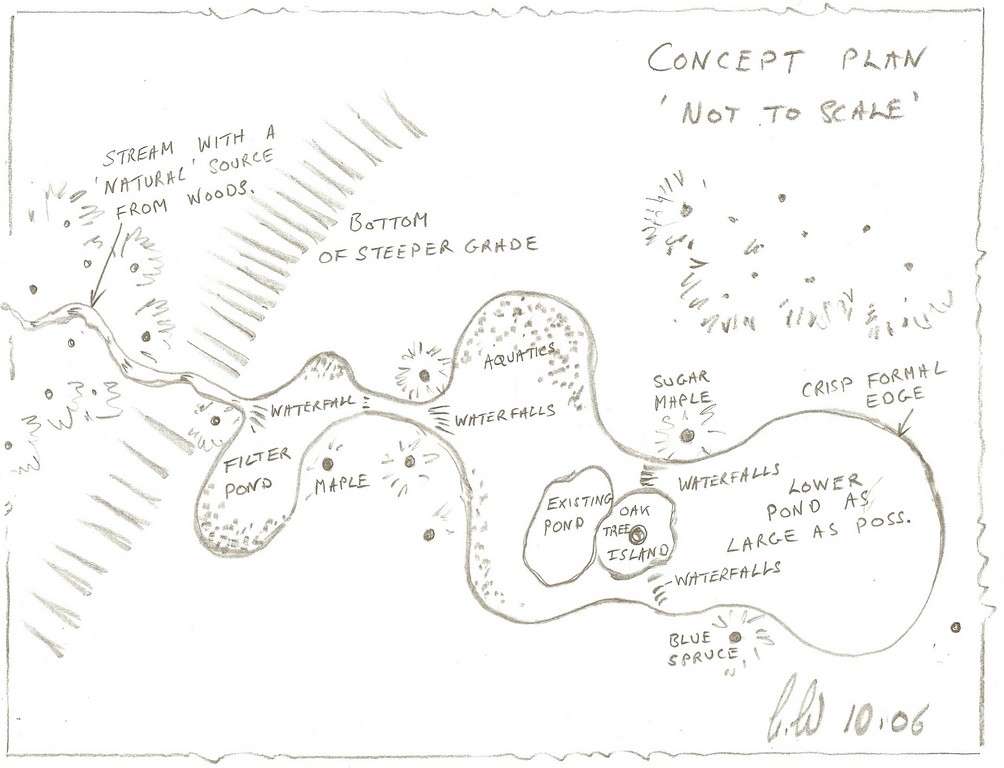

| As the design process moves along, I generate all sorts of drawings as a means of conducting my own dialogue with the site but also to draw clients and other members of the design team into the conversation as well. Here, for example, is a general concept drawing that gives everyone an overview: It’s far from literal and even farther from being set in stone, but it introduces them to my trains of thought. |

They agreed, and over the course of many subsequent conversations marked by their willingness to allow me a great degree of creative freedom, we went right to work in designing the overall scheme.

Through the years, I’ve spent a great deal of time refining my approach to such tasks. I lack a formal design education, but I’ve spent a lifetime speaking with and very carefully listening to people I admire, aligning what I learn from them with my own informal studies of great artists and various design traditions and, more particularly, with what I’ve observed in the grand and wonderful laboratories of nature.

In essence, what I’ve determined is that in approaching any design task – whether it’s an expansive one such as this or one on a far more modest scale – I must consider the entirety of the setting. I won’t, in other words, just drop in a pond or stream without considering the whole property and its larger context: how it works, how one moves through the space, where the views are (both within and beyond the property lines) and where sunlight and shade make their presences felt. Moreover, I do all I can to understand the clients and how they live and will use the spaces I’m developing for them.

TAME AND WILD

As I see it, I simply cannot leave any of these influential elements out of the process or I will invariably miss opportunities to forge the visual and emotional connections that will make these spaces work at their best for my clients and their guests.

In this case, as an example, when the homes in the area were first built, none were accessed by road; instead, residents and guests arrived at the local town by rail and were met by a steam yacht that carried them to the estates’ private docks. The result of this arrangement is that all homes on the waterfront were oriented to relate to the lake rather than to any sort of street.

By extension, this meant that these properties became wilder as one traveled uphill away from the shore and into the woods. This history directly informed the design: The planned watershapes were to emerge from the woodland in a naturalistic, discreet fashion and increase in splendor before terminating in a large pond adjacent to the home. Here, near this structure, the edge treatment was to be controlled and disciplined. Farther away, it would transition to a much more natural appearance and be marked by a series of waterfalls and wild plantings

Things would get increasingly wild as the system marched up the hill into the woods – the overall impression from the house being that you’re standing next to a long-tamed portion of an entirely natural water system that works its way down from the forest above to civilized spaces around the home and near the lake.

But I’m getting a bit ahead of myself here in offering an overview of the design solution that emerged: Before I go further, let’s double back and take a look at the fantastic canvas this project offered me.

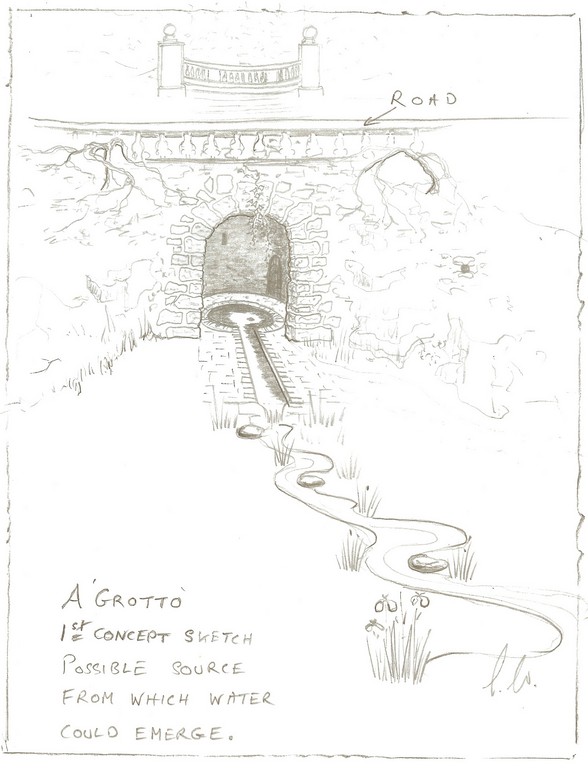

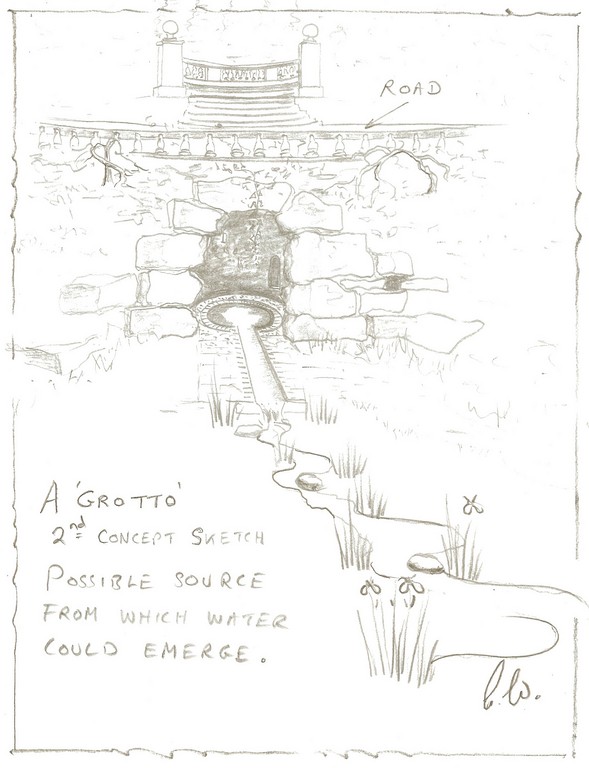

| When it comes to key details, a design will go through many iterations and variations as we move along. Here, for example, are two basic concepts for the water system’s headwaters, one in which the flow emerges from the slope as a natural spring, the other in which it rises (in formal and more rustic versions) from a font set in a grotto structure beneath the road. |

The overall space is quite large: approximately 600 feet wide and about 3,000 feet deep. Within that swath of land, I took my first steps by laying out in my mind what would ultimately become three major ponds connected by complex systems of waterfalls and streams.

As is almost always the case, there were some obstacles in the way – including the fact that, despite the lot’s size and location, the space is relatively flat. From top to bottom, although we were working with some 40 feet in vertical transition, almost all of it took place in the upper third of the space.

That might seem like a big drop – and indeed would be in another setting – but when cast over a space so large and with so much of the rise concentrated in one area, it’s really not so grand as all that. In fact, for the majority of the space the slope rose no more than about four feet, so I had to be unusually creative and very deliberate in planning transitions to make the most of what we had at hand.

This slope issue was exacerbated by a second challenge presented by the site’s mature trees. In one spot along the lower portion of the proposed system, for example, stands an oak that is probably more than 200 years old. It rises within reach of the stream course, with the crown of its root ball determining the top of the grade.

MAKING DO

What this meant, of course, is that we had to work very carefully around these obstacles to make certain we wouldn’t cause any damage – and, in fact, would succeed in creating the illusion that the tree had grown up alongside the watercourse.

The same issue we had confronted with that one beautiful oak came up time and again as we laid out our systems and were steadily challenged by the need to give priority to preserving the old trees. The only ones we could actually remove were either sick or damaged or compromised in some way, but those removals were few and far between. As a result, we were left to snake our way among many healthy, well-presented specimens to establish our watercourses. In so doing, I worked scrupulously beyond the trees’ drip lines to avoid any incidental damage in the here and now that might result in major harm later on.

On the plus side, this work gave us many chances to place the beautiful trees on promontories and at bends of the streams, giving these particular specimens the appearance of having taken root opportunistically in available land adjacent to the water.

Another challenge we faced had to do with the fact that the existing landscape was utterly devoid of natural geological formations and offered no visible rock outcroppings of any kind to work with. This meant that, for one thing, we’d have to bring in all the rock material to cover the entire job. It also meant that we’d have to extend those formations well into the landscape beyond the water to generate the impression that the water had been responsible for exposing the formations.

|

Natural Connection As mentioned in the accompanying text, one of the fundamental design concepts in this project involves creating illusory connections between our pond/stream system and the natural lake that fronts the property. We didn’t want to disturb the beautiful expanse of lawn between the house and the shore, so we agreed that the impression would simply be that the water in the ponds and streams flows to the lake via some hidden subsurface means – not an uncommon scenario in natural systems in the surrounding area. That concept, however, assumes a great deal: We knew we’d be asking observers to make the connection on their own – and although that’s not an unreasonable stretch of the imagination, I offered the thought that, at some point, we might further enhance the landscape (and the illusion of a connection between our water system and the lake) by inserting some sort of culvert structure near the lake. — A.A.W. |

These are, of course, specific installation details I wouldn’t be dealing with directly until we were well under way on site – and I won’t be discussing them to any further extent until we publish the next article in this series. Just the same, I know that I must consider such details from the start and anticipate what they’ll involve so I can accommodate their needs. Indeed, all elements must be considered at the planning stages to avoid problems and extra costs in the future: It’s about much more than figuring out the extent of the rockwork!

Early in the design phase, we also established that we would be dealing with large ponds and streams to suit the scale of the property, and that everything would appear to be flowing down the slope toward the lake (an appearance discussed in additional detail in the sidebar at right).

The house itself sits at the very bottom of the water system, in front of the largest of the three big ponds. To create intimate bonds among the formal gardens surrounding the home, the bottom pond ends in a crisp, formal, near-circular edge and acts as a mirror for the mansion’s beautiful architecture. As suggested previously, the idea was to make it look as though the water predated the home and that only portions of the system had been tamed for human occupation.

Another detail supporting this narrative is the beautiful limestone culvert placed near the top of the system where a road crosses the stream’s path. The idea here is that, when roads were eventually inserted around the lake to accommodate automobiles, this arched span had to be built to pass over an existing watercourse.

Now, as you enter the property by car, you first encounter the water as a very small stream up near the top of the drive and then see it at various points along the route. The impression given is that the system grows naturally in volume as it moves down the watershed.

FUN AND GAMES

As an overlay for this narrative, the owners made it clear from the start that they also wanted the project to include major elements of whimsy and play: The family includes young children, and the owners saw the pond and stream area as a place to encourage exploration and provide instructive entertainment.

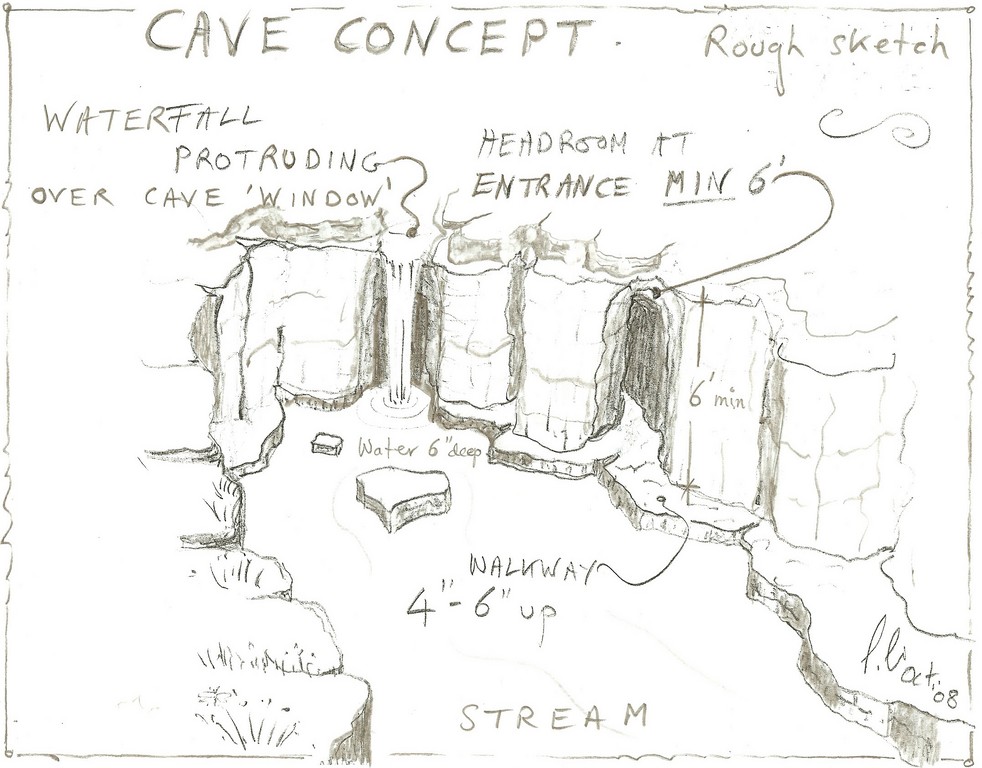

This led us to decide that, as part of the waterfall structure at the lower part of the system (quite close to the house), we would include a cave for the kids, with apertures through which they could peek out while hiding.

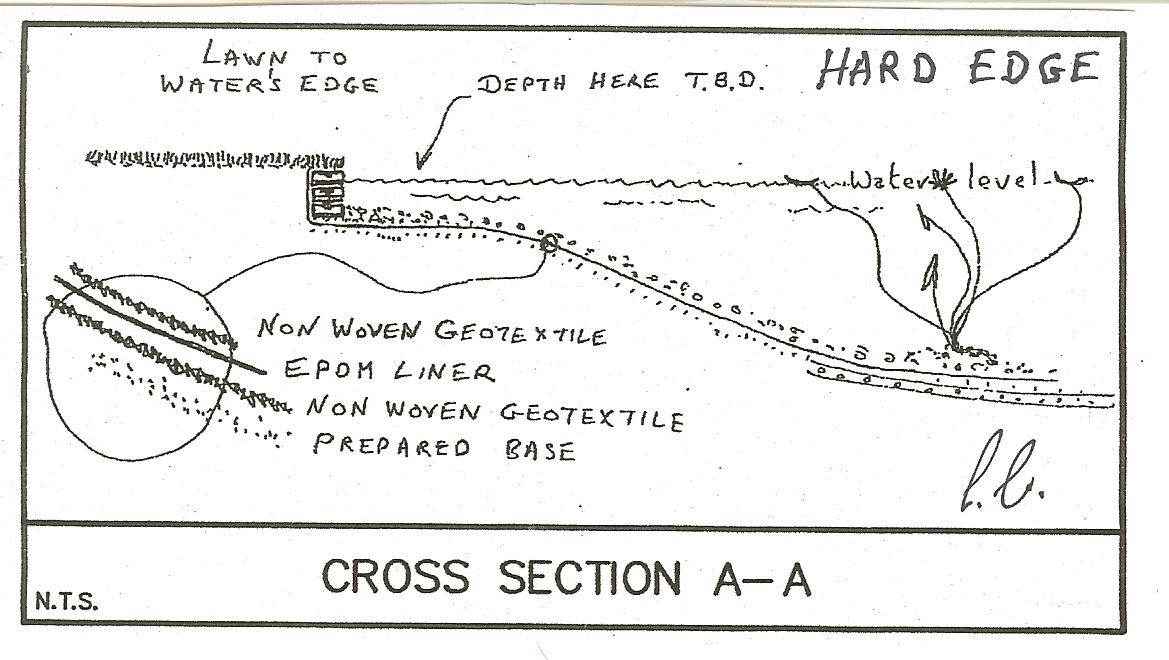

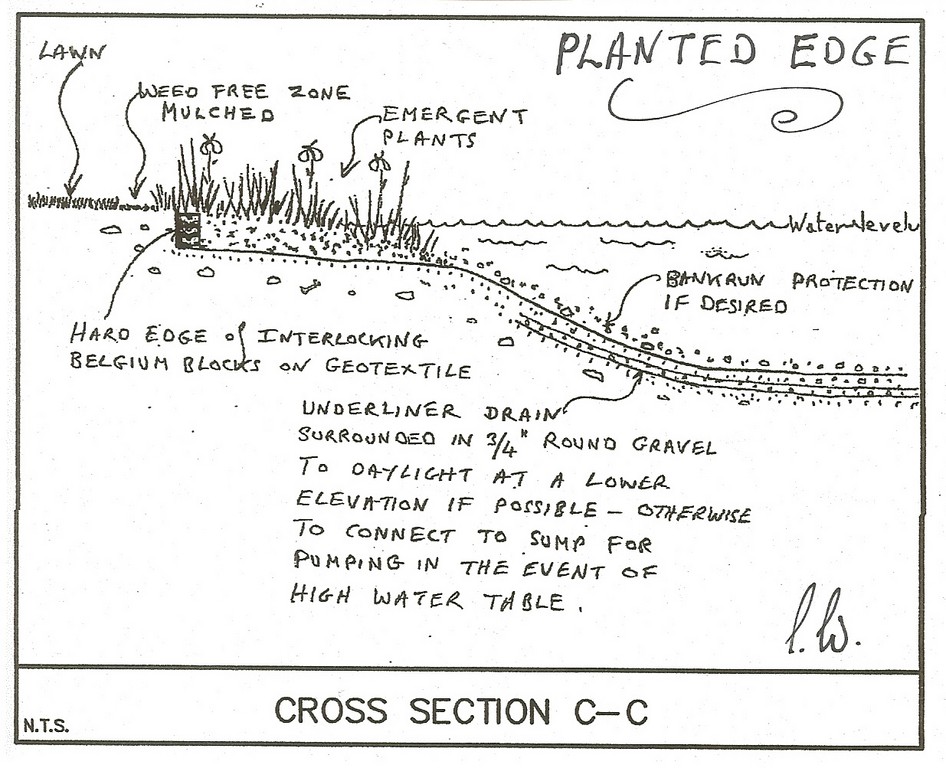

| In addition to sketches that are purely part of the creative process, I also generate drawings that serve as a guide for installation, helping the construction side of the team understand how everything will eventually come together on site. |

I’ll stay away from construction details at this point; for now, suffice it to say that, in designing with children in mind, provision of hiding places and secure observation points is the key to making these areas as much fun as they can be. Here, we devised a structure that could be accessed through a waterfall on the wet side and also by way of a small path running through an escarpment on the dry side.

This attention to the recreational needs of growing children was also a design focus beyond the cave system. Indeed, a good deal of attention was paid throughout the composition to establishing areas where children would be encouraged to interact with the environment.

This is why the design includes all sorts of pathways and turns and visual surprises and places to interact with the water. There’s also a raised, wooden walkway that crosses a portion of the stream near a waterfall and a number of places where the water may be crossed via steppingstones: These vantage points allow the family and their guests to interact intimately with the aquatic flora and fauna.

We didn’t entirely surrender the space to children, of course, but we applied the same spirit in mirroring the children’s cave upstream in the form of a cave behind the system’s highest waterfall made for adult use: We included hollows and hidden places behind the rocks, knowing that these details would appeal to the inner child in everyone who moved through the garden.

After many visits to the site and lots of conversations with the owners and the property manager – and with all of these concepts very much in mind – my next step involved walking the site and establishing boundaries for the water and various other features with ribbons and stakes. This took a while as I located and relocated the outlines of the ponds and streams.

| As concepts coalesce into plans, the drawings get more specific but not necessarily more detailed. Although we will indeed use these images as something of a guide once construction begins, there’s a great deal of improvisation on site – and participation by the entire crew in achieving the atmosphere suggested by the artwork. |

The property manager and homeowners were extremely helpful in what turned out to be several rounds of revising and editing – which brings up an important point: I believe that the best designers constantly revisit ideas to be sure they’re the best they possibly can be. Yes, sometimes an original kernel will persist from start to finish, but often the best solution for a given space can only be found by testing and retesting various ideas.

I might, for example, revisit a portion of a stream course and decide that part of the contour is gratuitous and needs to be toned down, or, by contrast, I might see that I need to play up a certain contour to create a sense of a natural battle between the water and the land’s edge. It is in striking these balances and defining these relationships that I invest a great deal of my time as a designer.

DOWN TO PRACTICALITIES

With the basic layout in place, it was time to plan the site’s basic structural elements (especially the waterfall/transition areas, all of which would have to be supported by structural concrete) as well as the hydraulic systems required to drive a truly massive watercourse. In the latter case, not only did we need to consider performance and aesthetics, but also had to factor in efficiency in operating costs and take an aggressive approach to keeping a lid on energy consumption.

On both fronts, I drew tremendous support from my frequent collaborator, David Duensing (David B. Duensing & Associates, Ponte Vedre Beach, Fla.), who always does an amazing job with issues such as plumbing and pump sizing and other technical aspects of the work.

His team was to handle the complexities of installing and jointing all of the pond-lining material as well as connecting the pipes and pumps. He would also work closely with the property manager, who had at one time had specialized in large electrical and hydraulic systems. The result of their collaboration is a system that moves lots of water while using many low-horsepower pumps and little electricity.

Indeed, the success of any project on this scale depends on the team – and in this case we had a winning combination: a forward-thinking, enthusiastic owner; a property manager who could make things happen and knew how to unclog logjams; efficient and professional earthmoving and general contractors; the aforementioned Mr. Duensing; and a delightful and supportive general staff.

I used the team to the fullest, establishing a portion of the design that they would either approve or offer suggestions of how things might be improved. Through it all, I generated countless hand drawings to help everyone involved visualize the details – edge treatments, water flows, plants – and keep all of us on the same general page.

| All of this creative energy was a prelude to a lot of hard work on site in which we would ultimately insert huge volumes of water where there had been none; work around existing trees while making them key components in the composition; create vertical transitions in what is basically a flat terrain; and introduce geology to a space devoid of it. All, as they say, in a day’s work. |

The process here was delightful. The only difficulty, in fact, had to do with the local preservation and historical society, which maintains strict standards and felt the need to review every detail to see that we were observing the rules to the letter – all understandable when a project involves changing a significant historic property. Happily, the vast majority of what we wanted to do was eventually accepted, the only real burden being the time added to the process while we obtained necessary approvals.

All told, in fact, these meetings and deliberations added a good six months to the process. The fallout of the delays was that, by the time we were ready to go, our window of opportunity had narrowed quite a bit, basically because of the weather. Our first phase – in which we were to build the bottom and middle ponds and their associated waterfalls – was compressed into little more than two months following the end of the Wisconsin winter and leading up to an important garden party.

Following that event, we returned for Phase Two and added the third pond along with the system’s biofiltration system. Above that level, we built the tall waterfall and its cave. Here, too, we faced a deadline in the form of another approaching winter.

In Phase Three, begun after winter’s retreat, we finished the cave and surmounted it with a pair of streams, one of which emerges gently out of stone outcrops we placed in the woods, the other of which issues from a limestone culvert – both convincing ways of giving the impression that water is entering the property from a watercourse hidden above. Having completed that, we addressed the landscape areas adjacent to the ponds and streams.

More on all of this construction activity will need to wait for the second article in this series.

Anthony Archer Wills is a landscape artist, master watergardener and author based in Copake Falls, N.Y. Growing up close to a lake on his parents’ farm in southern England, he was raised with a deep appreciation for water and nature – a respect he developed further at Summerfield’s School, a campus abundant in springs, streams and ponds. He began his own aquatic nursery and pond-construction business in the early 1960s, work that resulted in the development of new approaches to the construction of ponds and streams using concrete and flexible liners. The Agricultural Training Board and British Association of Landscape Industries subsequently invited him to train landscape companies in techniques that are now included in textbooks and used throughout the world. Archer Wills tackles projects worldwide and has taught regularly at Chelsea Physic Garden, Inchbald School of Design, Plumpton College and Kew Gardens. He has also lectured at the New York Botanical Garden and at the universities of Miami, Cambridge, York and Durham as well as for the Association of Professional Landscape Designers and the Philosophical Society. He is a 2008 recipient of The Joseph McCloskey Prize for Outstanding Achievement in the Art & Craft of Watershaping.