Public Interests

At its most basic, public art creates spaces in which people experience art without paying hard-earned dollars to own it or going to a museum or gallery to see it.

Public art is also about giving everyone within eyeshot new types of experiences amid their daily routines. Perhaps it’s an object they’ll pass on the way to the subway or an environment they’ll spot out of the corner of an eye as they drive to the grocery store. Maybe it’s a place where people gather to eat lunch or a landmark for arranging meetings with friends. Whether it’s familiar to the viewer or sneaks up unexpectedly, the work becomes a special, identifiable part of the landscape.

Sometimes these sculptures we see in public spaces are abstracted geometric designs or artworks that could just as easily be located in one public place as another. We also see traditional sculptures or fountains that, while beautiful, don’t have much to do with their surroundings. Many of these works are interesting, but I’m far more intrigued by artworks that emotionally connect with or evoke some aspect of a location’s history, geography or sense of community.

When public art makes this connection, it has the effect of turning up the volume on the experience of being in a given place. In addition to having the power to calm and soothe, artwork specifically integrated with a site also serves to resist the growing sameness of our society by expressing a community’s unique identity and a place’s role in the lives of local citizens. In doing so, public art prompts us to view ourselves as part of our surroundings, while honoring the individuality of a place and all who happen by.

CAUGHT UP

Before I started down this philosophical path, I studied the sciences, architecture and history – all of which regularly inform my work. Oddly, however, it was a job in commercial fishing that led to my first big break in art. It happened after a summer working at sea.

I’d had it in mind to make some sort of sculpture in a public place, but back then I didn’t know how to find places or ways to realize my ideas. While visiting a cultural-affairs office in Boston, I heard by chance that someone who had contracted to do holiday lighting over the street had backed out.

In a flash, I came up with the idea of suspending large fishing nets over the streets and using them to hang thousands of tiny lights. This gradually became a business in which, to this day, I make large displays with fishnets and lights – not about the holidays, exactly, but more about lighting up the winter sky in a festive way. This seasonal, decorative public art gave me a start, and I’ve since been able to move into more permanent installations.

Through all my work with nets and lights, I kept my focus on a conviction that public art works best when it is site-specific and carries special meaning for members of the community in which it is placed. The lighted fishing nets, for example, speak clearly of Boston’s history in commercial fishery.

Through the past eight years, much of my work has involved water and water effects that function in both conceptual and sculptural ways.

I’m drawn to these effects by the inherent power water has to attract attention and captivate viewers. (This is doubtless why fountains are among the most popular forms of public art.) We all share common experiences in and around water, whether it’s bathing, washing the dishes, swimming in a pool or walking along a stream or a river. Because of those associations, the constant change and variety that water lend to a space and a work of art engages us to the extent that most of us can’t resist breaking into gleeful smiles when we get close to it.

After I’ve used water in a project, I make a point of sitting back and watching how it is experienced. I love to see someone in the distance “discover” a water sculpture, then, almost as if a deep instinct takes over, change paths to get near it – and then become even more excited as he or she comes closer and gets to a place where the water can be touched. I work with all sorts of materials – stone, stainless steel and bronze chief among them – and bring water into the work whenever I can. These can be imposing materials, but my water projects are extremely accessible. I always think in terms of setting them up in such a way that people can get in them, climb on them and get wet.

Interactivity is a tremendous force, something that makes the observers active participants in their own experience. It’s amazing to see well-dressed people of all ages decide (often in small tentative steps) to get closer and closer – and, eventually, to get themselves completely drenched.

PROCESSING TIME

Taking the time to know the space I’ll be helping to shape is the key to my work. This working to forge connections with the history and geography of a place and the people who occupy it requires a design process that in my case includes extensive conversations with members of the community and others on the design team.

These are often projects created by and with the community, and I use all of the various community meetings – and there are very often a great many of them – as a venue for striking up personal conversations with those involved. I often find very useful information and insights that might otherwise get lost in the course of the usual meeting.

|

Public Purpose We live in times when public funding for artworks and public-space development is often in question and budgets for public amenities are steadily being cut. As our society becomes more complex, it is essential that we buck those trends and focus on improving our communal public places. On that level, creating watershapes for public places is an important gift to our culture, a way we honor our shared values and provide absolutely necessary places for gathering and celebration. — R.M. |

This level of research and conversation is not uncommon, especially in large landscape architecture projects, but my narrower aim is to elicit details and nuances that will enable me to infuse my work with symbolism and meaning that carries the work past the generic. I’m not looking for consensus; what I’m after is fuel for my creative process.

I often start a project seeking a wide range of images and concepts, even if they do not immediately seem practical or useful. I then try to visualize the ideas with simple sketches, quick cardboard models or tabletop scale models made with rocks, metal and wood along with water and light. Only then do I start to research technical solutions and specific materials for the fabrication/installation phases. This can be a cumbersome process, but I find that it also allows for fresh thinking and intriguing discoveries.

There are many trade specialists who have generously helped me along the way, and I like to combine the skills of people who have never worked together before – machinists and stone carvers who make special inserts into granite, for example, or lighting engineers and concrete finishers who work in tandem to get just the right reflectivity off a concrete surface.

I have been fortunate to find wonderful people to work with to develop unlikely solutions to some surprising problems. Ultimately, both the process and result are about discovery. It’s a true privilege to have the opportunity to engage this process with the outcome of creating meaningful public art.

The Shoe Fountain

Festival Plaza, Auburn, Maine

The town of Auburn is located an hour inland from the coast of Maine – not a traditional destination spot for tourists, but one with ambition.

The town’s mayor, Lee Young, is a forward-looking woman who headed up a $2.3 million campaign to create a park at the city’s center to give the downtown area a sense of place. The Shoe Fountain is part of that effort.

Auburn was once home to numerous shoe factories, and the industry was the city’s largest employer. The factories are now gone and the toll on the city’s economy has been devastating. The Shoe Fountain pays homage to this history while giving the town a new focus for pride and a more hopeful outlook for the future. It’s right in keeping with the town’s motto, Vestigia Nulla Retrorsum – that is, “no steps backward.”

The fountain is part of a large set of stairs leading to an open plaza on the bank of the Androscoggin River. Water flows over a granite weir and cascades over pink granite stepping stones set with gray granite cobbles. Nine cast-bronze shoes “walk” up the stairs on the stepping stones, each shoe equipped with a custom nozzle integrated with fiber-optic lighting that illuminates both the nozzles’ spray and the flow of the water over the steps.

|

All Lit Up Lighting is always an important piece of the experience of any outdoor sculpture – and particularly tricky when it comes to water. After several months of trials with experienced lighting consultants and numerous tests of everything from narrow-beam, low-voltage spots to submersible fiberoptics and remote floodlights, I was unhappy with all of the available approaches. As I kept at it, I began hearing about Sandra Liotus, a lighting designer who specializes in custom fabrication of fiberoptic lighting systems. After a few phone calls, her engineer, David Crampton-Bardon, visited my studio. We inserted highly illuminated ends of glass-fiber bundles into holes drilled directly into the nozzle’s water stream. By carefully tuning the angle of water and light, the light beam and the water stream became one, the light internally reflecting within the arched water stream and curving as it descends to light the reservoir/pool below. — R.M. |

John Ryther, a landscape architect with Icon Architecture of Boston, designed the space and brought me in to discuss waterfeatures that might be included. Lead architect John Shields had already designed the stairs; through a series of collaborative discussions, we developed the idea of adding water that would cascade down another set of steps that would run alongside the pedestrian stairs and wheelchair ramp.

Once the concept was developed, The Fountain People of San Marcos, Texas, helped achieve the water effects. I ordered several off-the-shelf fan-jet nozzles for a full-scale mock-up, and the shoes were chosen after sizing up many possibilities.

As it happened, we spotted some beautifully worn and patched shoes on the feet of an art student working in my studio. We made rubber molds, poured wax copies of the shoes, then shaped, distressed and distorted them to create individual variations. New England Sculpture Service, an artist’s foundry, cast the shoes in silica bronze, an alloy with a warm reddish tone. A chemical patina of ferrous oxide was applied, resulting in an amazingly shoe-like brown.

The Falls Fountain

Festival Plaza, Auburn, Maine

This fountain is located above The Shoe Fountain on a large plaza. Here the inspiration is the nearby Androscoggin River Falls, now often dry when the river water is diverted to a power plant.

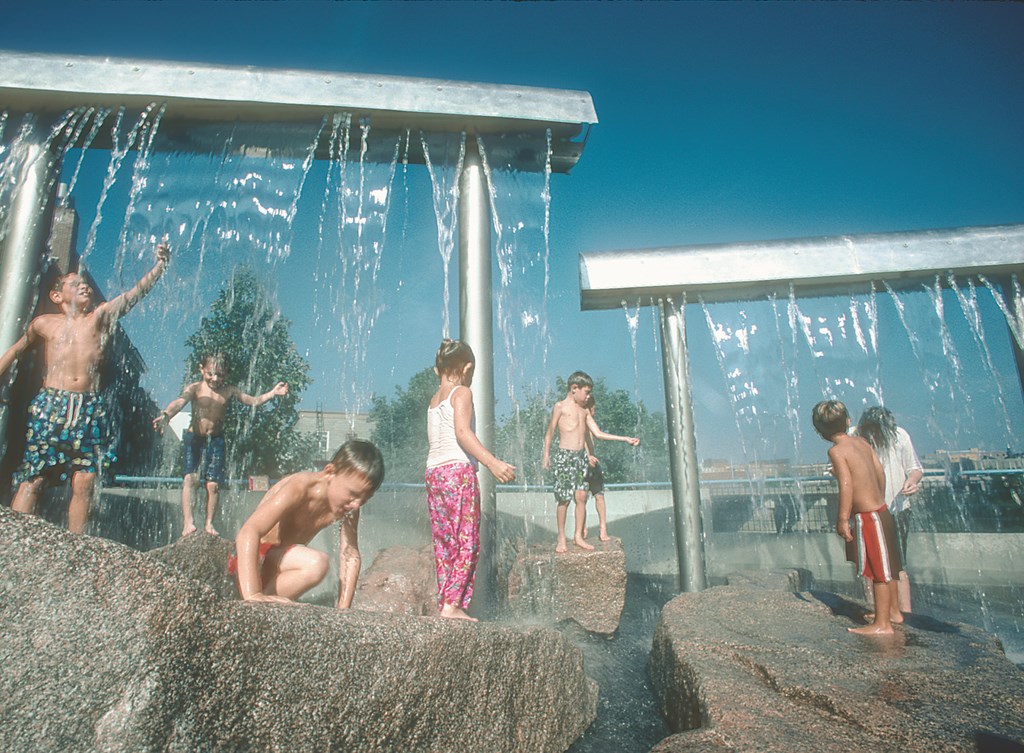

Local history tells of early Native Americans who used caves behind the falls for ceremonial purposes – and of settlers who later hid in the caves to avoid pursuit by those same Native people. The idea of these falls is to create a contemporary sculpture that enables visitors to move in and around sheets of falling water as a metaphor for the lost history of the river’s falls.

Large, upright, stainless steel structures contain plumbing, lighting fixtures and a total of 36 feet of sheeting waterfall nozzles that send water cascading over a field of pink granite boulders.

Lighting specialist John Powell suggested a series of narrow-beam low-voltage spotlights (aircraft landing lights) that are positioned within the overhead structure in line with the water flow. At night, light refracts magically through the streaming water and bounces off of the crystalline granite surfaces. Here again, The Fountain People worked closely with me to achieve the desired water effects with sheeting nozzles, fog nozzles and the circulation and control systems.

Beneath the sculptural waterfall, 45 tons of red and gray granite boulders are arranged so people can climb on them and interact with the water. All of the stones are between 16 and 24 inches tall, making them easily accessible by children and adults. In addition, many of the boulders are spaced far enough apart that people in wheelchairs can pass through easily.

To address the obvious safety issues, the rocks were flame-finished with a torch to create a rough surface that can be walked on with sure footing. The granite has its own story: It comes from Jonesboro, Maine, one of the state’s two remaining operational quarries. (At the beginning of the 19th Century, there were more than 400 granite quarries here.)

Fabrication of the fountain itself required the engineering of a complicated bulkhead and frame structure to hold the sheet bar nozzles, custom manifolds, fog system and lighting. All of the half-inch-thick 316 stainless steel parts were shaped with a computer-controlled water-jet cutter using a high pressure water stream carrying an abrasive garnet grit.

Although I like hands-on work, much of the design process involved in assembling these components took place with faxed sketches, emailed CAD files and phone calls between my studio and the custom fabricators, Maley Laser Processing of Warwick, R.I. Building the structure to hold these water effects was a collaborative design/build process that required full-scale mock-ups in plywood, then steel prototypes before final assembly by a skilled staff of machinists, welders and technicians.

The Fog Fountains

University Park, MIT, Cambridge, Mass.

This waterfeature was designed in collaboration with citizens of the city of Cambridge, Mass., for a new park set among biotech-research buildings on the edge of the campus of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In an unlikely twist on more conventional design processes, community protests and neighborhood activism led to plan revisions aimed at adding amenities for residential neighbors after the park had already started under construction. One specific and unanimous request was for a waterfeature.

Through this process, I learned that sometimes when political desire is effectively expressed, there are fast-track ways to get things done. In this case, change orders were issued and the park’s designers, The Halvorson Co., gracefully completed the extra design detailing.

The Park is built on land that was once a tidal salt marsh and later became the site of several 19th-century manufacturing facilities. We wanted to evoke the spirit of those bygone, misty shores.

The water effect here is all fog that rises at various timed intervals within a sculpture made up of stainless steel and granite cubes. A circular seat wall surrounds the entire water sculpture, inviting visitors to sit amid and enjoy the cooling mist. A series of cast-bronze oyster shells are located around the fountain, adding a measure of visual interest and directing the flow of run-off water. (These shells are based on real shells we unearthed on site during foundation excavation.)

The horizontal granite fountain base is sandblasted with patterns that catch and hold the mist. The designs are based on enlargements of electron-microscope images of chromosomes and recombinant DNA – a nod to the biotech laboratories that operate 24 hours a day in the adjacent buildings.

The fog system was developed by Mee Industries of Monrovia, Calif. The misting nozzles consist of small atomizers that work under extremely high water pressure. O find it interesting that the main applications for the company’s products include systems designed to prevent citrus groves from freezing in raw weather and systems that clean the air emitted from power-plant stacks.

In all, 24 nozzles are mounted within a stainless steel, woven-mesh cube at the base of the fountain. There’s also a small runnel carved into the granite around the perimeter of the fountain to collect the minimal runoff that condenses from the fog. Given all of today’s water-conservation concerns, this is a practical fountain!

The fog patterns change constantly, creating subtle variations. I did my best to capitalize on the transient quality of the effect. Observers need to pay fairly close attention at different times of the day and in different weather conditions to capture the dynamics of the composition.

Ross Miller is a Cambridge, Mass.-based visual artist whose work integrates art into public spaces to intensify community memory and create sites for private reflection in public environments. His desire to create water sculpture began at age 6, when he experienced a fountain designed by sculptor George Tsutakawa in Seattle. He is also an instructor for the Graduate Arts Administration program at Boston University, was a Loeb Fellow in the Harvard Graduate School of Design and directs Ross Miller Studio, Inc. Miller’s current projects include a fountain for the Boston Park Department known as the Ancient Fishweir Project, a design honoring 5,000 year old Native American structures buried under I-93 and the streets of Boston. He lives near the Charles River in Cambridge with his wife, Denise, and their daughters, Anna and Eva.