I've always been conservative when it comes to guaranteeing my work, which is why I only offer a 300-year warranty on my sculptures. I'm fairly certain that the vast majority of my pieces will last well beyond that span, but there's always the possibility one might be consumed by a volcanic eruption, blown up in disaster of some sort or drowned when the ice caps melt and cover the land with water. Those sorts of cataclysms aside, it's hard to imagine that the massive pieces of stone I use to create what I call "primitive modern" art will be compromised by much of anything the environment or human beings can throw at them. Ultimately, that's one of the beauties of working in stone: It possesses a profound form of permanence - and there's a certain comfort that comes with knowing my work won't be blown away by wind, eroded by rain or damaged by extremes of heat or cold. And given the fact that these pieces are so darn heavy, it's safe to say that most people are going to think at least twice before trying to move or abscond with them. Beyond the personal guarantees and despite the fact I don't dwell on too much, working with stone also has a unique ability to connect me and my clients with both the very distant past and the far distant future. Human beings have been carving stone for thousands of years, and many of those works are still with us in extraordinarily representative shape. There's little doubt that those pieces

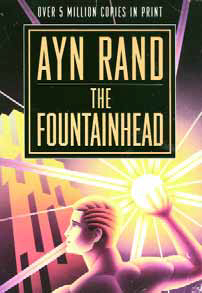

Every once in a while, I find it useful to read something purely for inspiration. Especially as the busy season heats up, I truly enjoy the thought of stepping away from the grind and getting lost in the pages of a good book. Most recently, I picked up Ayn Rand's classic, The Fountainhead (Penguin Books, 1994), and found not only a terrifically entertaining story, but one that I also see as useful on the professional front because of its many insights into issues of creativity, design and personal integrity. Let me start by saying that I'm not offering this unusual entry as an endorsement of Rand's controversial philosophy. There are plenty of ideas presented in this long, 700-plus-page book that don't align with the way I see things, and I have no intention here of commenting on Rand's "objectivism" in any way. To me, the core of the story is

In last month's "Detail," I discussed the beginning stages of a new project that has my partner Kevin Fleming and me pretty excited. At this point, the pool's been shot and we're moving along at a good pace. I'll pick up that project again in upcoming issues, but I've brought it up briefly here to launch into a discussion about something in our industry that mystifies me almost on a daily basis. So far, the work we've done on the oceanfront renovation project has been focused on a relatively narrow band of design considerations having to do with the watershape and its associated structures. This focus is

Contractors of all types are notorious for setting impossible-to-keep schedules, thereby disappointing clients and damaging their own credibility in the process. Sometimes, however, situations arise that require landshapers to shrink their established installation timetables, a necessity that will turn up the heat on even the most accomplished of contractors. For the project profiled in these pages, my clients had something come up that (from their perspective, anyway) necessitated completion of the project much earlier than anyone thought: They were expecting a baby and insisted that our delivery date should happen before theirs. The challenge we faced with the new timetable - just five months rather than the planned eight - was huge: It required truly constant interaction and communication with the clients and sub-contractors as well as intensive coordinating and expediting of a mind-boggling number of simultaneous processes - enough to drive us all crazy from time to time, but ultimately a

My clients' eyes light up when they first discuss color. They describe intense images of saturated reds, violets, and blues. The more color we can pack in, the better. No one yet has asked me for a garden awash in neutral grays. But what do they really want? As a landshaper, am I delivering the best service by designing a landscape overflowing with pure, vivid colors? As the hired expert, how am I to produce a landscape design that evokes the feeling they really want? That end result - the feeling, or emotional response, that the client gets from the garden - will not necessarily be achieved by placing bright colors everywhere. What we want is a garden that sings, not screams, with color. Of course to design this kind of garden, we designers must understand color ourselves. There is, unfortunately, an abundance of misunderstanding and misinformation on the subject. Let's aim at a more thoughtful understanding of color by approaching it in a logical, sequential manner. Let's explore how color really works, and how to design with color to form compositions that produce the feeling your clients

Think about what happens when rainwater falls on an impervious surface in a big outdoor parking lot studded by the occasional tree: The water dampens the surface, which instantly becomes saturated. Only a minute percentage of water that penetrates the trees' canopies to reach their curb-bound planters becomes available to the trees' roots. The rest almost immediately starts flowing to drain grates or perimeter drainage details and is lost to a stormwater-collection system. The trees are helped only marginally by the life-giving rain, and the water

Recent times have seen the introduction to the pool/spa industry of a new breed of hydraulic pumps that use what is known as 'variable frequency drive' technology. Here, watershaper, hydraulics expert and Genesis 3 co-founder Skip Phillips describes why he believes these devices, which have been used successfully for years in other industries that demand hydraulic efficiency, represent the future for pools, spas and other watershapes. For all the progress made in recent years to change the nature of the game, to this day I still see situations in which pumps, filters and other system components for pools, spas and other watershapes have, hydraulically speaking, been completely

Just as nature inspires art, I believe that art can inspire landscape professionals to "paint" themes and moods into gardens. Claude Monet's work is a striking example of this unconventional relationship between art and landscaping, a connection explored fabulously in Monet the Gardener (Universe Publishing, 2002), a collaboration between Sydney Eddison, who writes and lectures on gardens; and Robert Gordon, a leading authority on French Impressionism. Together, they delve into Monet's obsession with his famous garden at Giverny, describing his fixation on flowers and the struggles he had in creating his lily pond. Included are letters from Monet, members of his family, journalists and writers from the late 1800s, all of them chronicling the artist's choices among

Working in constrained spaces is entirely different from tackling projects that unfold in pastures where the only boundary might be a distant mountain or an ocean view. Indeed, in small areas that may be defined by fencing or walls or adjacent structures, the constrained field of view offers substantial aesthetic challenges to the designer in that every detail, each focal point, all material and color selections and every visual transition will be seen, basically forever, at very close range. When you're working small spaces, in other words, there's literally not much room for error. In this smaller context, each and every decision watershapers and clients make will subsequently be in direct view, and it's likely that each detail will take on special significance for the clients, positive or negative, as they live with the watershape over time. And on many occasions, what we're asked to start with as designers leaves much to be desired, including spaces already vexed by sensations of confinement, closeness or downright claustrophobia. To illustrate what I mean, let's take a look at two projects I recently completed in smallish yards for clients who wanted to