Rooting Out Problems

In an ideal world, tree roots would never be disturbed and decks, hardscape, structures and plantings would all avoid impinging on a mature tree’s space. Too few job sites, however, work that way: In our world of shrinking spaces, homeowners want as much useable space as possible, and this often entails building over and around tree roots.

In the process, contractors all too often cut through roots to accommodate footings and other structural elements and generally ignore trees and their needs for the duration of the construction project. As is also often the case, arborists are brought in to remedy problems only after irreparable damage to a tree becomes evident.

This is true despite the fact that trees generally serve as the anchors of our landscape designs and that most of us know that we should them with significant deference when designing landscapes and beginning construction. Typically, however, protecting a tree and its roots is a low priority for most general contractors and architects – and even some landshapers.

TREE-ROOT BASICS

We need only to understand the structure of trees and their roots to define why we need to protect them.

A tree’s health is largely determined below grade in its root system. These roots anchor the tree and store water and energy in the form of the carbohydrates, protein, starch and sugar that sustain the tree’s canopy (or foliage). Large buttress roots – six to nine inches in diameter and growing close to the trunk – stabilize the tree, while the rest of the root system expands to the drip line in much smaller diameters.

Fully 90 percent of a tree’s root system exists within 12 inches of the surface of the soil, while a majority of the fibrous roots – those that take in water and nutrients as their primary function – are all within the first six inches. The buttress roots are only a foot or two below grade and themselves are anchored by their own networks of fibrous roots.

| Many trees lack the fascinating root systems of these old trees and protecting their roots is not such an obvious requirement, but all established trees, regardless of what you see when you look at the soil around them, can be seriously damaged by thoughtless treatment during construction. |

Given the shallowness of this complex living system, it should be clear that cultivating or otherwise disturbing the soil around roots compromises their ability to take in nutrients or water. When this happens, the tree becomes susceptible to root diseases such as phytophthera, a water-mold fungus. When this happens, the signs of stress include thinning foliage, leaf drop, die back, color changes, size reduction and the appearance of dead wood up in the canopy.

In a healthy situation, the root system usually expands to twice the diameter of the tree’s canopy, reaching out to the above-mentioned drip line. A 20-foot-diameter tree, for example, would ideally seek to grow a 40-foot-diameter root system – a natural inclination frustrated in urban settings by streets, sidewalks, driveways and other structures.

On many sites, it’s possible to protect a mature tree during construction by fencing off the tree at a point beyond the drip line. Doing anything less and allowing traffic to pass over or materials to be placed within that area can compromise the health and structural stability of a tree.

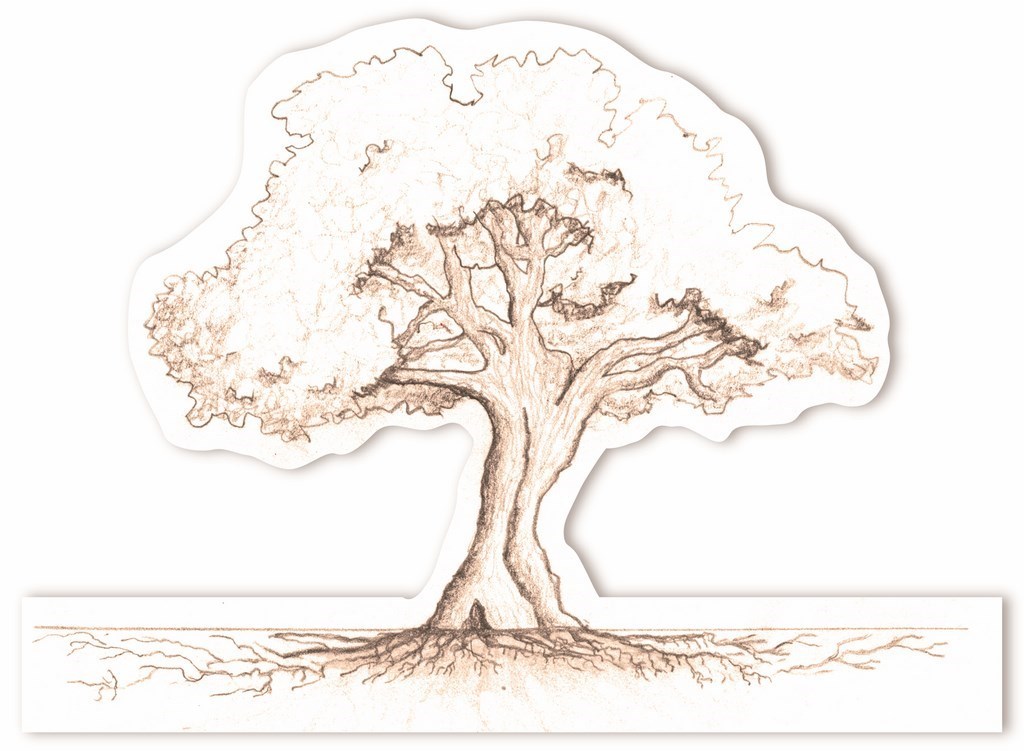

| This drawing illustrates a tree’s basic reality: Most of their roots live in the top few inches of soil in a range that reaches all the way out to and past the tree’s dripline. Compacting that soil chokes off a tree’s access to water and nutrients and can lead to devastating damage in the long run. |

If in doubt about what measures should be taken to protect a tree, all landshapers under all circumstances should consult with an arborist before construction begins to ensure that proper care is given to each tree – especially those of value to the client. Arborists will provide a report suggesting what measures should be taken. This might include, for example, fencing the tree off, layering the grade with four inches of coarse mulch to prevent compaction or various other procedures idiosyncratic to certain types of trees.

Before demolition begins, the first priority should be to establish guidelines for protecting any trees on site that the client wishes to keep. These guidelines should be included in written contracts with everyone involved, from the architect and landscape architect through to the general and landscape contractors, to define exactly how the guidelines should be followed. These documents also should specify a need for periodic inspections to make certain the guidelines are being followed.

These inspections should take place as frequently as needed given the type of work being done in the vicinity of the trees and the projected length of the construction period.

GETTING TO WORK

When initially reviewing a site, a landshaper should note potential problems with trees already on site. This would include information on which trees are to remain, whether the tree is right for the setting or not and what lengths the homeowners will have to go to protect the trees in need care and consideration.

The homeowner also must know how the presence of certain trees will influence design decisions. Coral trees, for example, have large, invasive root systems that emerge above grade as the tree matures, making them poor companions for structures and other plants.

There’s also the fact that in some areas certain trees are protected by law. In many California communities, for instance, Live Oaks are shielded to the extent that fines may be levied for disturbing the area within the drip line. This frequently makes building around these trees impractical.

All trees are different, of course, and have different requirements – but protecting the roots should be the primary concern in all cases.

The type of species sometimes dictates the recommended treatment. Weeping Willows, for example, are vulnerable to certain boring insects and diseases such as armillaria, a wood-rot fungus also known as oak-root fungus. For their parts, White Birch and Monterey Pines are more susceptible than other species to root system damage, whereas a Shamel Ash can often take more abuse than other varieties.

The age of the tree is also a major factor. Surprisingly, the older the tree, the less likely it will be able to withstand much root damage. Conversely, younger trees tend to be more resilient.

The simple fact is, no matter how old they are, trees need to be treated properly and appropriately during construction. This means that contractors should not, as often happens, shelter materials and supplies under or against a tree, as this results in soil compaction and keeps the roots from taking in oxygen. When oxygen depletion occurs, carbon dioxide builds up in the root system, the roots don’t breathe, root tips die and nutrient uptake is affected – all of which eventually shows up in the canopy.

| Neglect of trees’ needs during construction is bad enough, but what you see here amounts to abuse, pure and simple. Surely there were other shady spots for the portable toilet, better parking spaces for working vehicles and options when it came to positioning the dumpster? |

Similarly, if trees are not watered during construction, they can sustain drought-related injuries. Problems also result if lime or concrete wastes are dumped near trees, thus contaminating the soil and altering its chemical balances.

Thing is, there are a number of simple, effective ways to combat poor construction practices and protect the health of trees. Placing chain-link fencing two to five feet beyond the drip line and putting a four-inch layer of coarse woodchip mulch inside the fencing is a sure-fire protective program.

If a tree can’t be fenced off in that way – in, for example, a tight construction zone – at least the trunk can be protected from damage by attaching a wood girdle with a metal strap-ring. Backing a bobcat or backhoe into such a barrier will damage the two-by-fours instead of the trunk.

Mulching is also a good measure in any situation, tight spots included, and will prevent soil compaction by acting like a sponge to absorb the compacting energy of vehicle and foot traffic. The woodchip mulch has the added benefit of gradually breaking down into nitrates that feed the tree. Of course, the chips themselves can become compacted, which means the contractor should replenish them as needed during a project.

Watering is also critical, although this is dependent upon species in many cases. To determine how much water is needed, a soil probe should be used to measure moisture levels. For trees that need steady watering, placing a soaker hose inside the drip line will provide the needed deep watering.

In focusing so much on the roots, it’s easy to overlook the fact that the canopy has its needs as well. Upper branches, for instance, should be protected and pruned for clearance. Such pruning should, of course, be done at the right time of year and, preferably, before construction begins.

FOOD FOR LIFE

Periodic fertilizing is also essential if the tree is stressed, and it should ideally be done before, during and after construction depending upon the duration of the job. The main nutrient plants need is nitrogen, which they obtain from organic matter that breaks down into nitrates.

As was mentioned above, placing a layer of mulch on top of the soil is one way to deliver nutrients that will slowly leach into the soil. Coarse woodchip mulch breaks down over time and converts into nitrates – but it is also high in carbon and needs to steal microbes from the soil to break the carbon down, potentially robbing the soil of nutrients. (For this reason, fresh woodchips should be allowed to sit a minimum of six weeks before application to allow the mulch to degrade a bit and lose some of its carbon.)

By contrast, compost mulches are already decomposed and their nutrients are quickly available to the tree – but they will also disappear more rapidly than woodchips as soil microbes do their work. The decision to use woodchips or compost will depend upon the soil, tree species and site. They can also be combined, if that’s a solution that makes the most sense.

Beyond basic protection and feeding, the proper design and construction of hardscape surrounding the tree is critical. These processes must take the tree’s needs into consideration, and any resulting structure must accommodate those needs while maximizing homeowners’ access to increasingly scarce available space in their yards.

| Protecting trees at job sites is a reasonably straightforward process and involves setting up barriers of some kind to forestall foot traffic and serve as a constant reminder that the space right around the tree is not to be used as storage space (however temporary) for construction materials. |

Decks, particularly in drought years, stress trees by reducing water supplies to the root system. In situations where a deck must be built over roots, the best solution is a wood structure (ideally raised about 12 inches above the existing soil level to facilitate the use of soaker hoses underneath). The basic rule is that the soil around the roots of trees should never be cultivated and that it’s best to place a layer of mulch over them. In this context, a raised wood deck is the least-intrusive option.

It’s also important to keep decks as far away from tree trunks as possible. A gap of four or five feet is ideal, depending upon trunk size. The goal should always be to minimize any disturbance of the buttress roots, particularly when installing any footings or substructures for the deck.

Exploring the space with an air spade is the most effective and protective method for finding roots without doing them any harm. This device moves the soil away from the roots using highly pressurized air, avoiding the scarring sort of damage that may occur with manual digging.

If a deck is impractical but there’s still a need to cover the area close to a tree trunk, cobbles placed around the base of a tree offer an attractive solution with no drawbacks. The cobbles won’t encourage foot traffic right around the tree in the way a deck will, and they can offer a great visual solution without compacting the soil, disturbing feeder roots or limiting watering or feeding. A single layer of stone is ideal, especially when kept six to12 inches away from the trunk to prevent moisture build-up against the base.

Whatever is used, no ground-covering structure should be built near a tree in a way that alters the existing grade. Raising soil levels around the trunk or root system is the worst offense imposed against trees during construction and effectively suffocates the root system while promoting root rot. Conversely, digging into the grade to place a deck will rip away roots and will stress the tree dramatically.

PLANTING ISSUES

It’s not just decks that are a concern: Ideally, all of the space within the drip line should remain uncultivated as well, because planting within that area cuts and damages roots while the cut roots excrete sugar, which in turn makes the tree more vulnerable to root rot – the leading cause of tree death.

A mature tree suddenly underplanted with shrubs will inevitably suffer. It is unrealistic to think that we could avoid planting at all under mature trees, but it’s important to inform homeowners whenever this potential for damaging the tree’s health exists.

If you’re installing a new tree of any size on site, it’s best to underplant it with species that won’t compromise the tree when it matures – that is, plants that will thrive in the shade as the tree matures and whose roots will harmlessly intertwine with the tree’s feeder roots. Naturally, there will come a time when the landscaping will need to be refreshed and a decision will need to be made at that point about updating the plantings: All such decisions should be made with full awareness of their implications for the tree’s health.

If a tree is properly underplanted, all plant material will be kept away from the base and trunk of the tree. Close plantings will smother the root crown, increasing the chance of armillaria and phytophthera invading the tree. (Just think of a tree as a piece of lumber: If it’s constantly moist, the wood will rot and eventually disintegrate.) The vital systems that supply nutrients to the canopy are less than a quarter of an inch from the surface of the trunk. If damaged, the flow of nutrients to the canopy is impeded.

| The same trees that need protection during construction will also benefit from longer-term strategies that will keep their roots in good health. In these cases, rocks have been used to prevent compaction and provide access to air and water, but just about anything that discourages traffic (wood-chips mulches, for example) will do the job. |

Accidents do happen, of course, particularly when the guidelines provided to landshapers, general contractors and architects are not followed. If an uninformed (or unsupervised) subcontractor cuts a buttress root, a tree will immediately be compromised. If this happens, an arborist should be called in immediately to check for signs of stress, thin out the canopy to balance the tree’s weight, test for structural safety and reduce the weight load on the root system.

The tree should then be inspected every four to six months, basically for the rest of its life: If a cut is made too close to the trunk, damaging decay may not appear immediately, but it could potentially create a structural problem years down the line. This is a costly lesson to learn and is an accident that no contractor should ever allow to recur!

There are also situations in which a landshaper will come on site late in the construction process and something will already have been done that has compromised a tree – a masonry deck, for example, built over an expanse of soil within the drip line. In such cases, remedies can be extreme, including removal of the infringing material.

If the site calls for the use of masonry decks near trees, it’s recommended that very porous materials be used. Stone or brick set over sand, for example, allow air and water to get to root systems. There are also some newer permeable-concrete materials may offer an alternative. Bottom line: Around trees, materials that repel water or nutrients should be avoided at all costs!

The list goes on: Landshapers should. For example, plan appropriate drainage systems if the situation requires installation of masonry decks from which runoff will flow and deliver excessive water to root systems. Good drainage systems can help, but homeowners should know that trees left in these conditions will be stressed and will never be at their best.

We’ve moved through a lot of information in a short space, but it’s clear that a little understanding of the nature of trees and their roots – coupled with some basic protective and preventive techniques – can help a landshaper pull virtually any tree through the strains of construction in fine shape. The key is making certain homeowners share in this awareness of the pitfalls of working around trees so they can get involved in what are truly life-or-death decisions for their trees.

Nickolas Mook owns and operates Mook’s Arbor Systems of Woodland Hills, Calif. Since receiving his bachelor of arts degree in environmental science from Chadwick University, he has been certified as an arborist by the International Society of Arboriculture, has become a licensed pest-control applicator for agricultural crops in the state of California and earned certification as a turf grass manager from the University of Georgia.